History Rhymes: Why Societies Under Stress Become Violent

For everything that happens, there are reasons for it to happen. That doesn't necessarily make it painless.

Image created by Seedream 4.5

A wave of madness is engulfing the world. On this point, at least, we can all agree. Then, what’s causing it? Charles Hugh Smith makes an interesting comparison between the Cultural Revolution in China and the current unrest in the US. In both cases, we have a society in which a leadership facing a serious risk of being toppled unleashes a wave of violence to deflect the public’s resentment and hate. For China, it was the “enemies of the people”; for the US, it is the Left and immigrants. In this view, the ICE police would be the equivalent of China’s Red Guards. And an aging leader, such as Mao Zedong, finds his equivalent in another aging leader, Donald Trump.

These phases of madness are typical of societies under heavy stress, where a necessary change has been repressed for a long time and where, at a certain moment, the only way to keep it repressed is to use violence. There are several examples in history: Nazism in Germany, the French Revolution, the Roman Empire lashing out at Christians, and others. There are other cases. As usual, history rhymes: ordinary people are the typical victims of the wave of violence.

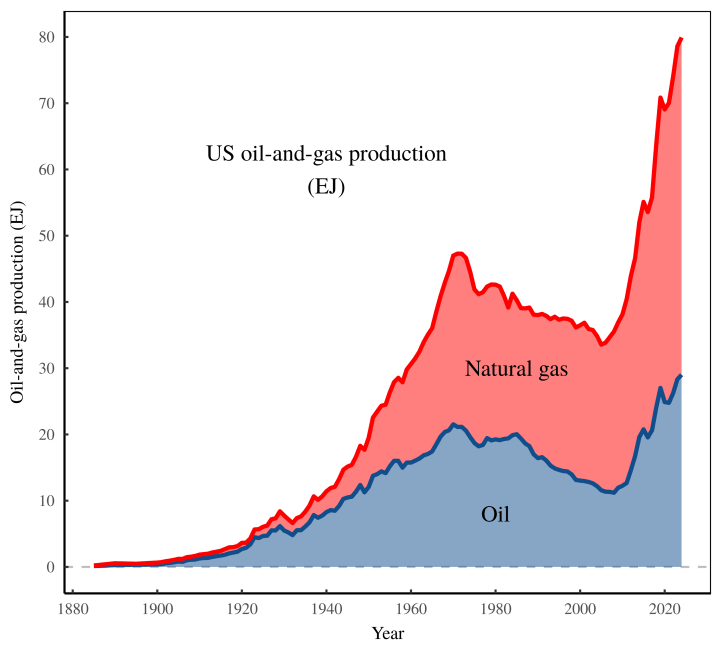

But why is the US society under such a heavy stress? A good summary of what’s happening can be found in a recent post by Blair Fix, who gets everything right about the oil situation (as he usually does on most subjects on which he writes)

Blair Fix summarizes the story of the US oil production, from the beginning to the start of a decline that looked definitive after the peak of 1970. Then, as now, a country which based most of its prosperity on oil production and exports found itself in a phase of uncertainty, unrest, and violence.

But the US could turn the tide with a technological trick: shale oil. By “fracking” previously inaccessible deposits, the oil industry could restart the growth of oil production and put the US back into its position of top dog among the world’s states.

But, now, the second oil peak is coming for the United States. It is the harsh law of depletion. It is not that the industry is running out of resources; it is that extracting them becomes too expensive for the market to produce a profit. And a resource that doesn’t produce a profit is a purely paper resource. You may as well say that it doesn’t exist.

We are getting to that moment for shale oil. It was always expensive, and it produced only modest profits, if any. Now, people are starting to realize that the bubble is going to explode, not only because of depletion, but also because of the switch of the world market from liquid fuels. The euphoria of just a few years ago is gone, and it is becoming clear that we have reached the second US oil peak. This was commonly said and discussed among people involved with the oil industry. What wasn’t understood, so far, was that the second oil peak could lead to the second US civil war.

What we are seeing now is a gang war among various power groups in the US (if you like to call them “mafias,” it is a good definition). They are trying to turn the impending collapse of oil production into an advantage for their specific turf. The oil industry is trying to get financing for more drilling in the US, no matter how bad the returns could be. The military gang plans to invade or subdue oil-producing countries to take control of their reserves (it is already happening with Venezuela). Then, there is the nuclear lobby pushing for new nuclear plants, although so far with modest success, as it is unavoidable for a product that’s too expensive and too slow to arrive. The renewables lobby is still weak in terms of clout, but it is gaining space in the economic system. The agricultural lobby is still hoping that some of their products will be turned into food for cars, rather than food for people. Even the coal industry is making noises in terms of proposing a return of its dark product. Finally, the hi-tech industry doesn’t care so much about who wins, but wants energy for their big AI toys.

In this situation, the Western government structure is pathologically unable to make decisions that would benefit society as a whole. It can only support the lobby (or cosca mafiosa if you like) that pays more. It is not surprising that the struggle is turning kinetic. Mr. Trump is mostly controlled by the oil lobby, and he is trying to slow down the introduction of new energy technologies, especially the dreaded electric cars that could snuff out the main market of the oil industry. In the end, the struggle creates two camps: those who want everything to stay the same, and those who want change.

Trump and the current MAGA bunch are straight in the first camp, those who are pushing the brakes on the energy transition. They probably realize that the only way to stop an unavoidable change is to freeze the situation by military means. In other words, create a dictatorship that will control the US economic system and direct investments in the direction of benefiting the oil lobby and the military-industrial complex. The other camp is a motley group of ineffective lobbies that tend to quarrel with each other. As things stand, the military/oil alliance is likely to win, at least in the short run.

It is, as usual, history rhyming. All declining empires go through a phase of militarization, just before they completely collapse (you may call it “military Keynesianism” if you like). It is the Seneca Effect: for the new to appear, something old must die, but that’s not pleasant nor painless.

________________________________________________________________________

An Excerpt from Charles Hugh Smith’s Post

The second lesson of the Cultural Revolution is that allowing--much less encouraging--the unleashing of frustrations with the system on ill-defined “enemies of the people” who are innocent quickly spirals out of control. In the Cultural Revolution, the targets quickly expanded from those in authority positions in the Party to anyone deemed suspicious for any number of reasons: being educated, having traveled to other countries, being the offspring of the landlord class, being the offspring of a purged official (like Xi Jinping being abused because his father had fallen from grace), or simply being an object of envy.

This expanding circle soon included cultural relics of the past, and so irreplaceable Buddhist temples and other priceless artifacts were destroyed out of “revolutionary fervor.”

The third lesson of the Cultural Revolution is that once these forces are released, it is impossible to put them back in the bottle. Those in power reckon that unleashing a flood tide of resentments and frustrations with the system on a selected group of scapegoats relieves the potential risk of the public revolting against the regime.

But this ignores the potential for the injustice and chaos to destabilize the regime, for the injustice and destruction don’t just affect the scapegoats; they undermine the social, economic and political orders, too.

Just as nobody foresaw the Cultural Revolution, few if any foresee the emergence of the American equivalent. The consequences of expectations not being met build up despite repression and narrative control, and when the containment finally bursts, the dynamics are nonlinear--chaotic, unpredictable, uncontrollable.

Everything is forever until something unexpected breaks

An excerpt from Blair Fix’s post

When it comes to the exploitation of non-renewable resources, what’s up for debate is not if the rate of harvest will peak and decline, but when this peak will occur.

Here, some recent history seems relevant. Back in the mid 2000s, peak-oil theorists stridently predicted that world oil production would soon peak. In hindsight, these folks were wrong … but not entirely so. The production of conventional oil peaked in 2005, more-or-less as predicted. However, total oil production did not peak, largely because the production of non-conventional oil exploded. Since this non-conventional oil more than made up for the decline of conventional oil production, talk of ‘peak oil’ basically died.

From this episode, there is a wrong lesson and a right lesson to be learned. The wrong lesson is that oil is so abundant that its exhaustion is nothing to worry about. The right lesson is that oil production will peak, but the timing is difficult to predict, because it depends on technological and social factors that early peak-oil theorists failed to appreciate.

Because the United States is at the epicenter for the growth of non-conventional oil production, it seems useful to use it as a case study. While the timing of the second peak of US oil production remains uncertain, there are signs that all is not well in the US oil patch. Let’s have a look.

Consider hypercomplexity vs complexity. The US and UK are hypercomplex, stuck in the acceleration of acceleration (jerk - 3rd derivative) of their growth economy. France, Germany and the rest of the EU economies are still in the acceleration of growth (2nd derivative). France and Germany can manage a contracting economy. The US and UK cannot. They will just crash. The Americans and Brits see this happening at the ground level. That is why they are wallowing in despair. If you can get out of these two countries, do so. If you cannot get out, reduce your lifestyle to a minimal level and keep your head down.

Already mid-70s it could have become clear that long-term economic planning was absent in the US. "Short term profit" was the policy that (in part) was forced on some vassal states too. In a consumer-based economy, outsourcing well-earning knowledge-based workers already was a case of slow-motion suicide. Substituting production with casino-like activities has a short expiry date as well. The empirical rule, countries run by lawyers (like US) double down on what doesn't work whereas countries run by engineers look far ahead and adapt long before problems arise.