The first case in history of a fruitless military campaign for mineral resources was the one launched by Emperor Trajan against Dacia for the gold of the Carpathian region. Many other cases can be listed in modern times, but the recent story of the alleged “500 billion dollars” (or trillions) worth of rare earth minerals in Ukraine has a peculiar twist. Instead of justifying a military campaign, it may have the purpose of disengaging the US from Ukraine.

When Emperor Trajan attacked Dacia in 100 CE, he was trying to gain control of the gold mines of the Carpathian region in Central Europe. At that time, the Roman Empire's main source of wealth, the gold mines of Northern Spain, were starting to show signs of depletion. So, the Romans were desperately searching for new sources of gold.

After two harsh campaigns over five years, the Empire gained control of Dacia. But the results were disappointing. The debasing of Roman coins during that period shows us that the war strained the Empire’s resources to the utmost while bringing little or no gold into the Imperial coffers. The problem was not that the Carpathian mines didn’t contain gold but that the Roman mining technology of the time could not extract it at a profit. (See below for a detailed description of Trajan’s campaign).

There are other examples of fruitless military adventures in search for mineral resources. At the time of the Spanish conquest of South America, there was the search for “El Dorado,” said to be a city endowed with fabulous gold riches. Later, there was the “war for oil” on Iraq in 2003. But the most egregious example is the invasion of Afghanistan by the United States, which started in 2001. It was the consequence of a wrong assessment of the oil resources available in the nearby Caspian Region. It lasted more than 20 years and brought back not a drop of oil (I describe the story in a post on the “Seneca Effect”)

So, what should we say about the recent spat of news about Ukraine, said to contain huge (“yuuge”) amounts of mineral resources? Ukraine is not a mythical place like El Dorado, Shangri-la, or Hyperborea. Could the Soviet (and later Ukrainian) geologists have missed the presence of hugely profitable mineral resources there? Unlikely, to say the least. And yet, we are told that they did. Here are some recent statements by President Trump.

Note that Trump is a moderate in comparison to other members of the US administration. Senator Graham Lindsay recently said that Ukrainians “are sitting on a trillion dollars worth of minerals that could be good to our economy.” To make sure the message is clear, others have inflated the size of the booty to 15 trillion dollars. I even saw it raised to 26 trillion dollars.

Obviously, these are just numbers invented out of whole cloth. For a bit of immersion in reality, you can look at the “USGS mineral commodities survey” of 2024. and you’ll find that there are no rare earth resources in Ukraine. Nothing, zero, null, zilch, nada, rien de tout.

That doesn’t mean that somewhere in Ukraine, there are no exploitable mineral resources of one or another kind. The USGS report says that Ukraine has abundant iron resources, then some titanium, gallium, bauxite, lithium, and a few more possibly exploitable resources, such as coal and uranium. But all mineral resources have a cost of extraction, and if the cost is higher than the gain, they are not resources.

Those promoting the Ukraine story ask us to believe that minerals extract themselves by their mere buoyancy, then purify themselves by magic, and finally transport themselves to the points of use by floating in mid-air — all at no cost. And that the pollution costs of production are also zero.

Now, what is the purpose of this game of make-believe? The people telling us this story surely know that the rare earths in Ukraine are such stuff as dreams are made of; the same kind of gold you find at the end of the rainbow. Mr. Trump claims to be a good businessman. What would he think if someone presented him with a business plan listing only the gains but not the costs?

On the other hand, something bad for business may be excellent as a political tool. Everyone knows that stealing from thy neighbor is not a good thing, but when told that thy neighbor is rich, then both the left and the right take the bait. The right because they believe that might makes right, the left because they can blame the right for being evil (but they believe the same thing, even though they won’t say it).

The case of Ukraine has a peculiar twist: it doesn’t seem to be an excuse to send troops there. Instead, it looks like an excuse to throw Ukraine under the bus (better said, under the tank). You know, we made such a big effort for those Ukrainians, sending them weapons aplenty, helping them in many ways, and now these cowards not only can’t defeat the Russians, but they even refuse to give us a honest compensation for what we did for them. They don’t deserve our help!

It is a strange case of a non-war for non-resources. But if mythical rare earths are used as a trick to end the war, I have to say that these people are admirable in a certain sense. True masters of deception, they play with the naiveté of the public as if they were violin virtuosos. And the public seems to love being played — it is unbelievable how easily they fall into these traps. Most people are completely unable to verify the messages they receive from the media, even though it would take just a few clicks to do that.

From the time when Rumsfeld said that reality can be created, we became real-life Cinderellas, easily convinced that if we keep on believing, the dream that we wish will come true.

_________________________________________________________________

From Cassandra’s Legacy, 2014 (slightly edited)

Gold and the beast: a brief history of the Roman conquest of Dacia

Roman soldiers bringing civilization to Dacia (from the Trajan column in Rome). The Roman Empire invaded Dacia at the beginning of the 2nd century AD, seeking control of the Carpathian gold mines.

The ascent of the Roman Empire is best understood if we think of it as a beast of prey. It grew on conquest by gobbling its neighbors, one by one, and enlisting them as allies for more conquest. By the first century AD, the Roman Empire had conquered everything that could be conquered around the Mediterranean Sea, which the Romans called “Mare Nostrum” or “Our Sea.” But the beast was still hungry for prey.

And what a beast that was! Never before had the world seen such a force as the Roman legions. Well organized, trained, disciplined, and equipped, they were the wonder weapon of their times. The great innovation that made the legions so powerful was not a special weapon or strategy. It had to do with a concept dear to the military: command and control. In the Roman system, it was based on gold and silver. The Romans had not invented coinage but systematically used gold and silver coins to pay their soldiers. So, the size of the Roman army was not limited by the Roman population: almost anyone could enlist either as a legionnaire or as an auxiliary fighter; his reward was money. Gold was, in a sense, the secret weapon of the Roman Empire; it was the blood, the lymph, and the nerves of the beast of prey.

Because of its command and control system, the Roman army could grow in size using a self-reinforcing mechanism. The more gold the Romans had, the larger their army could be. The larger their army, the more gold they could raid from their neighbors. The more gold the Romans had, the more they could invest in extracting more gold from their Spanish mines. The beast kept growing bigger, and the more it grew, the more food it needed.

But even the mighty Roman legions had their limits. In the 1st century AD, the Spanish mines started showing signs of depletion. At the same time, the Empire had reached practical limits to its size and the amount of gold it could loot from its neighbors. In 44 BC, the legions had been stopped at Carrhae in their attempt to expand in the wealthy East at the expense of the rival Parthian Empire. In Teutoburg in 9 AD, a coalition of German tribes had inflicted a crushing defeat on the legions, stopping forever the attempt of the Romans to control Eastern Europe. There were no other places where the empire could expand: in the West, it faced the ocean; in the South, the dry Sahara desert. Confined in a closed space, the beast risked to starve.

Not only could the Roman Empire not get any more gold, but it couldn't even keep the gold it had. The Roman economy was geared for war and couldn't produce much more than grain and legions, neither of which could be exported at long distances. At the same time, the Romans had a taste for expensive goods they could not produce: silk from China, pearls from the Persian Gulf, perfumes from India, ivory from Africa, and much more. The Roman gold was used to pay for all of that, and slowly, it made its way to the East through the winding Silk Road in central Asia and from Africa to India by sea. It was a wound that was slowly bleeding the beast to death.

With less and less gold available, the legions' power could only decline. That the Empire was in deep trouble could be seen when, in 66 AD, the Jews of Palestine - then a Roman province - took arms against their masters. Rome reacted and crushed the rebellion in a campaign that ended in 70 AD with the conquest of Jerusalem. It was a victory, but the campaign had been exceptionally harsh, and the Empire had nearly gone to pieces in the effort. Nevertheless, the empire had brought home a considerable amount of desperately needed gold and silver. The beast was eating itself, but for a while, it was satiated.

With the gold plundered in Palestine, the Roman Empire could gain some time, but the problem remained: where to find more gold? At this point, the Romans turned their sight to a region just outside their borders: Dacia, an area northeast of the Empire that included Transylvania and the Carpathian mountains. The beast was smelling food.

We don't know much about Dacia before the Roman conquest. We know that it was a thriving society that was expanding and that it probably had ambitions of conquest of its own, so much so that the Roman empire had agreed to pay the Dacian kings a tribute. We know that the Carpathian region had been producing gold in very ancient times, and there is evidence (Bogden et al.) that, at the time of the Roman conquest, the Dacians were mining gold veins in the Carpathian mountains. It may well be that they had learned new mining techniques from the Romans themselves. So, Dacia was probably experiencing a gold mining boom. It was a prey in the making.

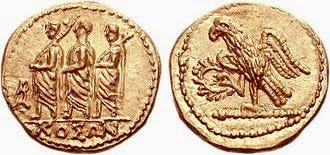

The Dacians may have had plenty of gold, but they were still building up their economy and technology. The only gold coins that can be said to have a specific Dacian origin are a curious mix of Roman iconography and Greek characters spelling the term "Koson," whose meaning is uncertain. We don't even know if these coins were minted in Dacia. It is possible that the Dacians sent some of their gold to Rome to have it transformed into coins and brought back to Dacia – not unlike what oil producers are doing today when they send their oil to the United States to be transformed into dollar bills. The Romans must have been happy to work with the Dacian gold, but they must have noticed that the Dacian mines were producing it. So, it a military conquest of Dacia could pay for itself. The beast had sighted its prey.

In the year 101 AD, a young and aggressive Roman Emperor, Trajan, invaded Dacia. It was a bold attempt, given the rugged terrain and the strong resistance of the Dacians. Surely, the nightmare of the Teutoburg disaster of nearly a century before must have haunted the Romans but, this time, the legions overcame all obstacles. After two campaigns and five years of war, the gamble paid off, and Dacia was transformed into a Roman province. The beast had made another kill.

We have no reliable data on how much gold and silver the Romans looted in Dacia. We also know that the Romans invested in the Dacian mines, probably bringing in their expert miners from Spain. However, the effect seems to have been negligible on the Roman economy. If we look at the data for the silver content of Roman coins (data from Joseph Tainter) there is no evident effect of the Dacian conquest.

We see an increase in silver content at about 90 AD, but that's a decade before the Dacian campaign, and we may attribute it to the inflow of precious metals deriving from the conquest of Palestine. Instead, the Dacian campaigns correspond to drops in the silver content of coins: evidently, the Romans had to debase a little their currency to pay large numbers of troops. But the conclusion of the Dacian campaigns didn’t cause the Roman coins to contain more silver — at most, we see a brief period of constant content. Evidently, the Dacian mines couldn't match the wealth that the Spanish mines had produced in their heydays. The beast had become too huge to be fed just with crumbles.

Perhaps because of the disappointing results of the conquest of the Carpathian region, Trajan attempted another bold project: expanding in the East. In 113 AD, he attacked the Parthian Empire. But after some initial successes, the Romans had to stop. Asia was just too big for them to conquer. The beast had found a prey too big to swallow.

With the death of Trajan in 117 AD, the new emperor, Hadrian, took the decision to stop all attempts of the Empire to conquer new territories, a policy that all his successors basically kept. In a sense, it was a wise decision because it prevented the Empire from collapsing. However, the final result was unavoidable: gold continued to bleed away from Roman territory and could not be replaced. The Western Empire, which included the city of Rome, disappeared forever after a few centuries as an impoverished shade of its former self. The beast was to die of starvation, slowly.

And Dacia? Over nearly two centuries of Roman rule, it was "Romanized." The Dacian cities adopted Roman customs and the Latin language. But Dacia was also one of the first Roman provinces to lose contact with the central government when, around 275 AD, the legions abandoned it. For comparison, Britannia was not abandoned before 383 AD. We have no data on gold production in Dacia during this period, but the simple fact that the Romans decided to abandon the province means that the Dacian mines were producing very little gold, if any. There was no food left for the beast. It died shortly afterward.

Left alone, Dacia was exposed to all the invasions that were to sweep through Europe in the period we call “The Great Migrations.” Apparently, however, Dacia maintained its Roman roots better than Britannia. Today, the region is called “Romania,” and its people speak a Latin-derived language, even though we have no records of a Dacian King who bravely fought the Barbarian invaders, as King Arthur is said to have done in Britannia.

This brief survey tells us a lot about how important gold is in human history. For the region that we call Romania today, the gold mines in Roșia Montană, in the Carpathian Mountains, have been a fundamental element. Exploited from remote times, these mines have periodically experienced new waves of exploitation as technological improvements made it possible to recover lower and lower-grade gold ores. And with these cycles of boom and bust, there went invasions, migrations, kingdoms, and empires. The cycle continues today with a project to restart exploiting these ancient mines using the last technological wonder in gold mining: the cyanide leaching process. But getting more gold from the exhausted Carpatian mines is costly and the damage it could do to the land is tremendous. The drop in gold prices of the past few years may soon make these new gold mines too expensive even to be dreamed of. Even existing gold mines may have to be closed.

So, it looks like the beast of prey that, today, we call "Globalization," is facing the same problem that the old Roman Empire was facing in its times: the disappearance of the vital minerals it is preying upon (and gold is just one of them). Since today there are no perspectives of conquering unexploited lands, it is an unsolvable problem. The globalized beast will have to die of starvation, it will survive only if it will accept to change its diet.

Ugo--

A few posts back, you compared large language models in an exercise that subverted our faith in the ability of language to represent reality or contain anything resembling intelligence. You followed that up with a discussion of memes as images or words as contagions of meaning that by definition were distortions of reality--or damned lies, as we refer to them locally.

Today's post brings up the ability of imagined riches to establish speculative economies which dwarf economies based on production of goods. Perhaps the first meme was the word gold with an exclamation point.

That Rome persisted long after it was economically viable shows the power of a speculative economy, and it looks as if the American Empire will persist far longer than its basis in the real world, for better or for worse. A substantial majority of humanity lives in a world of words, one where plenty is a function of keystrokes.

Language fails only when humans are forced to reckon with the mine that doesn't produce, the crop that fails, the enemy that destroys a power plant or refinery. For a moment, one is freed from the burden of naming everything one sees, but that isn't exactly a happy outcome.

Hello Mr. Bardi, It only took a few days to pass and facts you laid out here played out in the press a few days later when it looked like the scam was exposed, but now stories in the press seem to have returned to support the assertion that there are minerals to exploit in Ukraine and that they have value in regards to negotiations.

If there were precious minerals there that were exploit-able, they would have been in the Soviet years. That alone seemed obvious to me, even if you and others had not presented other elements supporting the non-existence of the precious rares.

But now that the ephemeral mass of "fried air" has been created, it can be tossed about like a coveted beach ball in whatever farce negotiations ensue.

Additionally, if all parties agree that the "emperor's" clothes are the finest they've ever seen, the holders of the tailoring rights can leverage loans and sell speculative shares based on the future potential on the markets!

Recall when the Bush II cabal convinced the US folk to war on the premise that the spoils of Iraq's oil would pay for the war -and bloated "reconstruction" costs?

This "rare earths" scam feels like a rhyme.