Grabbing Greenland's Oil. But does it Exist?

When Politicians misunderstand the concept of "mineral resources"

Emperor Trump 1st wants Greenland. But why did he set his eyes on this remote piece of land? Is it because of the “immense oil resources” said to lie below the Greenlandic ice sheet?

Have you noticed how fast food hamburgers look gigantic when you see them in pictures? But when they arrive on your table, your mind is immediately captured by the meme of the old lady screaming “Where’s the Beef?”

Greenland has the same problem: because it almost always appears on maps as a “Mercator Projection,” it looks as if it is as big as the whole of Africa. In reality, it is less than 10% of the area of Africa.

Greenland has a historical problem with being advertised for what it is not. It goes back to the time of Erik the Red, the Viking, who described it as “The Green Land” in the early Middle Ages, probably to attract colonists there. Then as now, Greenland had strips of green on the edges, but mostly it was (and still is) a huge crust of ice. The first Norwegians who migrated to live there couldn’t survive for long and died of starvation and cold.

So why did Donald 1st set his eye on Greenland? As often happens in such cases, there is talk of “immense mineral resources,” oil and others, that Greenland is supposed to contain. But do these resources really exist? And are they worth a war to grab them?

Greenland is not the only place said to be up for grabs because of its mineral resources. Senator Graham Lindsay recently said that Ukrainians “are sitting on a trillion dollars worth of minerals that could be good to our economy.” Any economy would find that a trillion dollars of resources are a good thing, but, to make sure the message is clear, others have inflated the size of the booty to 15 trillion dollars. Recently, I saw it raised to 26 trillion dollars.

Wonderful. If it were true. But already the fact that these numbers grow so fast makes you suspect that we aren’t talking about anything real. Money is a virtual thing that you can create out of nothing, so it can grow without limits. But that’s not true for real world things as mineral resources are supposed to be.

The problem with these wild estimates is not so much whether the supposed minerals exist or not. The problem is that to give a value to something, you must subtract costs from revenues: that’s the way business plans are made. But, miraculously, mineral resources are supposed to prospect themselves with no efforts needed, to extract themselves without the need of energy and equipment, to refine themselves without the need of refining plants, and finally, to teleport themselves to the points of use without the need of ships, trucks, or pipelines. All this at zero cost.

A good example of this delusionary approach is that of the “immense oil resources” that were supposed to exist in the Caspian region, in Central Asia. I tell the story in detail in a post of mine that I reproduce at the end of this post. It may be that 20 years of military occupation of Afghanistan, with all the included human and material costs, were just the result of a misunderstanding of the numbers in an USGS report published in the 1990s.

How about Greenland’s mineral resources, and oil in particular? The question has been talked about for at least 20 years, when Jean Laherrere, one of the world's foremost oil experts, criticized certain overoptimistic estimates by the USGS (United States Geological Survey) saying, more or less, look, nothing is going to be pulled out of Greenland for at least the next 20 years. And he was absolutely right.

There may be some oil under the ice sheet in Greenland, or maybe offshore, but the costs of prospection and extraction are staggering considering the uncertainties, the lack of infrastructure, and the prohibitive weather conditions. Not to mention that starting now, nothing could begin to be produced for at least a decade, probably more. By that time, oil as a source of liquid fuels will be as obsolete as coal for steam locomotives.

So, the idea of conquering this or that region to grab its “immense mineral reserves” is just an excuse to give some money to the military industry and some prestige to politicians. It is a slogan that is not so different in practical terms from others, such as “bring them democracy” or “let’s fight them there so that we do not have to fight them here.” In early times, it was enough to say “Deus Vult” ('God wills it').

This is not to say that Trump is a fool. Absolutely not; on the contrary, in my opinion, he is smart. Annexing Greenland requires little effort (56,000 inhabitants in the whole island) and it would give Trump the prestige of adding a new state, the 51st, to the union. The last president to do this was Eisenhower, who annexed Hawaii and Alaska. And why shouldn’t someone who can grab something not grab it? Think about that; it is the way things go in the world.

_____________________________________________________________________

Here is a translation of a post that I published in Italian in the “ASPOITALIA” website in August 2004. It illustrates the story of the Caspian oil delusion up to 2004. I added a short update at the end.

THE CASPIAN OIL FEVER.

By Ugo Bardi

The Caspian oil fever started in the late 1990s, when it became fashionable in the West to speak about the "immense reserves" of crude oil that could be found in the area around the Caspian Sea. So rich was this region supposed to be that it would be possible to turn it into a "New Saudi Arabia" (sometimes "A New Persian Gulf"). But the story had started much earlier than that.

Already in mid 19th century, the first oil wells of the region were dug near Baku in the Azerbaijan. In 1873, Robert Nobel, the brother of Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, led an expedition southward from St. Petersburg. He found in Baku, on the Caspian shore, an already operating oil industry. Nobel invested in this industry, developing it considerably. At the end of the nineteenth century, Baku was the largest oil-producing area in the world, even surpassing the American oil industry of the time.

At the beginning, oil was mainly turned into kerosene and then used as fuel for oil lamps. Our great-grandparents' lamps in Western Europe were almost certainly lit with oil supplied by the Caucasus mining industry. With the development of the internal combustion engine, in the early twentieth century, oil began to be used more and more as a fuel. The strategic value of the Caucasus fields was already important in the First World War, when the shortage of oil was one of the factors that caused the defeat of the Central Empires. But it became evident with the Second World War which was, in many ways, the first, true "war for oil."

When the Germans invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, one of their main strategic objectives was the oil fields of the Caucasus. In the offensives of 1941 and 1942, the Germans tried to advance towards the Caucasus, but the battle of Stalingrad put an end to their attempts. That was the turning point of the war. Had the Germans succeeded in taking hold of the Caucasus, history could have been very different (and maybe you would be reading this post in German).

After the Second World War, the Soviet Union began to find difficulties with expanding the production of oil from the Caucasus. From the 1950s onward, the reserves of the Urals, the Volga region, and eastern Siberia were the main target for development. These reserves made the Soviet Union the largest oil producer in the world until about 1990.

By the end of the 1980s, the Soviet oil production began to show signs of difficulty and, in 1991 the production peak was reached, with decline starting afterward. At the same time, there arrived the collapse of the Soviet Union itself. There are many interpretations of the reason for this collapse, but it is possible that the decline of oil production was not a consequence but the main cause of the collapse of the Soviet Empire, the political structure that was created to exploit it.

This story tells us a lot about the situation in the Caucasus after the fall of the Soviet Union. Since the oil fields had been exploited for over a century, we should not be surprised if they were depleted and declining. But the Western oil industry looked with some interest at the Caspian area, believing that their superior technology could extract oil not accessible to the Soviets. As early as in 1985, Harry E. Cook, of the United States Geological Survey (USGS) began exploring Central Asia for possible new oil reserves. Later, under Cook's leadership, a consortium called “USGS-Kazakhstan-Kyrgyzstan Oil Industry project” was formed which included ENI/AGIP as well as BG, BP, ExxonMobil, Inpex, Phillips, Royal Dutch Shell, Statoil, TotalFinaElf, and several ex-Soviet research institutes.

The first contract with the consortium to export Caspian oil to the West was signed in 1994. It turned out to be a difficult task because of the need to carry equipment to a remote geographical location, not accessible by sea. It was necessary to wait until 1999 before it became possible to export Caspian oil through the Baku-Novorossiirsk pipeline, which ends on the Black Sea. From there, the oil could be shipped worldwide.

But in the 1990s a virtual kind of oil that existed only in the minds of people had also appeared. The story started in 1997 with the publication of a U.S. Department of State Report: (U.S. Department of State, Caspian Region Energy Development Report, April 1997). (a version of the report can be found at this link).

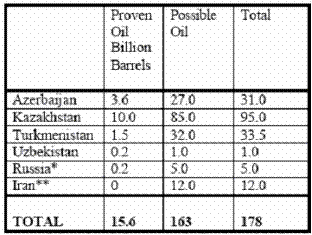

In the report, the following table could be found:

It seems that the data of the report were derived from Cook's work stating that the Kashagan field could hold up to 50 billion barrels, a value that had been further inflated here to 85 billion, so that the total for Kazakhstan arrived at a whopping 95 billion barrels. The total amount of "possible" reserves in the area was estimated at 178 billion barrels of oil. It is not clear what the authors meant by the term "possible oil." In the practice of reporting oil reserves, the term "possible reserves" is normally coupled with a probabilistic estimate, usually 5%. So, what the table said was that there was "a 5% chance of finding 163 billion barrels"

Such a statistical estimate was incomprehensible to the average politician and these data were badly misunderstood. The first political exponent to speak publicly about the discovery of new, "immense reserves" of the Caspian Sea seems to have been the US Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott in 1997. Talbot used on that occasion, perhaps for the first time, the phrase "reserves up to two hundred billion barrels of oil."

Talbot had rounded up the "possible reserves" to 200 billion barrels. Other people spoke of 250 billion, and in some case, you heard of 300 billion barrels. If these estimates were true, it would have meant that the Caspian could have increased the global oil reserves of about by 20%, not a trifle! But the main effect of these new reserves would have been to drastically break the quasi-monopoly of OPEC countries and the Middle East on oil and completely changing the geopolitical framework of world oil production. This was the origin of the enthusiasm about "A New Saudi Arabia" that could exist in the Caspian region.

As the exploration proceeded, the available data was further processed. In 2000, the USGS released a report signed by Thomas Ahlbrandt that arrived at an estimate of world reserves at least 50% higher than all previous estimates. This report was criticized by many experts and contradicted by the trend of subsequent finds, but it was another of the elements that led to the myth of the Caspian Sea as a new oil El Dorado.

The "200 billion barrels" story began to generate doubts from the moment it appeared. Already in 1997, a report by Laurent Ruseckas to the United States congress scaled down the estimates by speaking of a "possible maximum" of 145 billion barrels, a value that had to be taken as an unlikely extreme, with a reasonable maximum value of around 70 billion barrels. Ruseckas also pointed out that someone was getting too enthusiastic.

Skepticism rapidly began to spread. A 1998 article in Time magazine stated that if these estimates were correct, the Caspian region could contain "the equivalent of 400 giant fields," yet there are only 370 giant fields in the world (Robin Knight, “Is The Caspian An Oil El Dorado? Time Magazine, June 29, 1998, Vol. 151 No.26). In 1999, a report presented to the SPD group in the German parliament (1999 by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Washington Office 1155 15th Street, NW Suite 1100 Washington, A.D 20005) was titled, significantly, "No longer the 'Great Game' in the Caspian". In one section of this report, Friedemann Muller stated that: "The often reported figure - preferably by politicians of a certain age - 200 billion barrels is a figment of the imagination ”. The issue of inflated reserves also appeared in the popular press, for example, in a November 11, 2001, Toronto "NOW" article, Damien Cave described the Caspian estimates of 200 billion barrels as "insanely optimistic, at least in the next twenty years."

The real world started intruding into the fantasy of politicians when the OKIOC consortium (ENI, BP, BG, ExxonMobil, Inpex, Phillips, Shell, Statoil, and TotalFinaElf) started actually drilling at the bottom of the Caspian sea. Apparently, the results were not impressive, since the consortium began to fall apart after the first exploratory drilling. By 2003, ExxonMobil, Statoil, BP, and BG had left. Agip remained and became the main operator of the consortium. In April 2002, Gian Maria Gros-Pietro, then the president of ENI, speaking at the Eurasian Economic Summit in Almaty, Kazakhstan, declared that the entire Caspian could contain only 7-8 billion barrels. Others have estimated up to 13 billion barrels for the Kashagan field alone. For the whole area around the Caspian Sea, it is possible to speak of amounts between 30 and 50 billion barrels. These reserves are not negligible but available only at high costs and certainly not a new Saudi Arabia.

By the early 2000s, the situation was reasonably clear, at least in the eyes of the experts. Colin Campbell, the founder of the Association for the Study of Peak Oil (ASPO) summed it up like this in a private communication to the author of these notes.

“There were rumors that the area contained over 200 Gb [billion barrels] of oil (I think those rumors came from the US Geological Survey), but the results after ten years of construction have been disappointing. As early as 1979, the Soviets had found the Tengiz field on the mainland in Kazakhstan. It contains about 6 billion barrels of oil in a limestone reef at a depth of about 4500 m. This oil, however, contains up to 16% sulfur, which was too much even for Soviet steel, so they chose not to exploit the field. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Chevron, and other American companies arrived and managed to extract that oil, but with many difficulties and at high economic and environmental costs.

Later, in a series of surveys made on the bottom of the Caspian Sea, a huge structure was found at about 4000 meters deep that in many ways resembled that of Tengiz. This area (Kashagan) also had geological features similar to those of the giant Al Ghawar field in Saudi Arabia. Had it been full, it could have actually held 100 billion barrels or perhaps more and competed with Saudi wells.

At that point, an American businessman, Jack Grynberg, put together a large consortium of oil companies that included BP, Statoil, Total, Agip, Phillips, British Gas, and others. This consortium set out to exploit the deposits thought to exist in this facility.

Exploratory drilling has been enormously difficult. The field was offshore, so it was difficult and complex to transport equipment to the area. In addition, those waters were a breeding ground for the sturgeons that produce Russian caviar. Finally, the winter climate of the area is harsh with ice formations on the surface of the water and very strong winds. Eventually, at a cost of $ 400 million, the consortium managed to drill a 4,500-meter deep well in the easternmost area of the facility. A deadly silence followed, followed shortly after by BP and Statoil's withdrawal from the company. British Gas announced in a report that the field could contain between 9 and 15 billion barrels. The reason is that,- unlike Al Ghawar - the field is very fragmented with the fields separated by low quality rocks. It is an interesting field and it is certain that further reserves will be found, but it is certainly not capable of having any significant effect on world supplies. There is a lot of gas nearby, but the transportation difficulties are immense. "

Nevertheless, the two worlds, that of the politicians and that of the experts had decoupled from each other and plenty of people were still believing in the existence of "200 billion barrels" in the Caspian region. From the left, the "immense reserves" of the Caspian were cited. as proof of evil Western imperialism. From the right, there was a clamor to get their hands on that bonanza as soon as possible. As an example, we can cite the speech that US Senator Conrad Burns, who had traveled to Kazakhstan himself, gave to the Heritage Foundation, on March 19, 2003

"Every dollar we spend of Middle East oil, we are really dealing in rogue oil. Money that goes to build weapons of mass destruction and also the fuel those terrorist groups that need money to operate around the world," Burns said. "We don't have to look to the Middle East, because the reserves in the Caspian Basin could be as large as what is in the Middle East"

and:

Internationally, our country is ignoring the opportunities that exist in Russia and in the Caspian Sea basin. In the Caspian Sea area, reserves of up to 33 billion barrels have been found, a potential greater than that of the United States and the double that of the North Sea. Estimates speak of an additional 233 billion barrels of reserves in the Caspian. These reserves could represent up to 25% of the world's proven reserves. Russia may have even more abundant reserves.

These numbers are all wrong. For one thing, the North Sea reserves are estimated at around 50 billion barrels, and 33 is certainly not double 50. As for the "255 billion barrels", added to the other 33 make a total of 288 billion of barrels, which is out of the grace of God. But, clearly, Burns was not the only American politician who thought in these terms. And much of what happened after the 9/11 attacks of 2001 can be explained as an attempt by the US government to take direct control of the strategic oil fields of the Middle East and of Central Asia. Not for nothing Conrad Burns was a convinced supporter also of the invasion of Iraq.

In the end, it doesn't seem to be paranoid to think that the United States attacked Afghanistan in 2001 in order to clear the field at the passage of an oil pipeline from the Caspian that would reach the Indian Ocean passing through Pakistan. A grand dream, if ever there was one. But there were no "immense reserves" in the Caucasus and, therefore, no need for a pipeline to transport them. And reality, as usual, eventually took over.

____________________________________________

Update (2025). The exploitation of the Caspian Oil reserves is progressing, with Kashagan having recently reached a level of production of about 380,000 barrels per day. Not bad, but much less than what true “giant” fields can do, considering also the poor quality of the oil being extracted. Nothing even remotely comparable to “A New Saudi Arabia” and Kashagan will never be the “game changer” it was supposed to be.

The value of Greenland doesn't depends on its mineral ressources only. But also on its strategic position near new sea lanes between Asia and the Atlantic. Pretty much the same as Panama incidentally.

And actually, it looks like there will be a deal. At least, it seems to be Trump's idea. Russia would get the Donbass (and maybe the Odessa area on top of it) and Poutine will let Trump get Greenland. Of course, Europe, with its exhausted economy and its pile of debt, will not have a choice in the matter.

By the way, Zelensky has already understood where the whole thing is going. He declared that Ukraine will not support any American pretention on Greenland. As if anyone asked him his opinion...

Of course, the USA will not buy Greenland the way they bought Louisiana or Alaska. With a price tag and all. Europe will get an export tax deal it won't be able to refuse and/or a nice discount on US weapons, on natgaz or whatever. Then US companies will be allowed to do whatever they want in Greenland and will be backed by strong and unchallenged military presence monitoring naval activities. And soon enough, Greenland will look pretty much like the Samoa or Puerto Rico (some kind of protectorate instead of a new state because it would mean 2 senators for only 50 000 people).

By that time, oil as a source of liquid fuels will be as obsolete as coal for steam locomotives.

hahahahhahaha ... that's meant to be a joke... right?