An episode of the “Dragon Blade” film (2015). It features a song that the Ancient Romans never sang and an encounter with a Chinese community that never took place. Yet, the movie conveys an eerie fascination about something that could have happened if the two Great Empires of ancient times had met somewhere in the middle of the Eurasian Plains. Eventually, Chinese and Westerners will have to meet each other and become friends. But we’ll need to avoid the mistakes of the past that led to three major commercial wars that unbalanced the whole world.

The Chinese Government's reaction to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic was unexpectedly drastic. The SARS-Cov2 virus eventually turned out to be a minor threat, but the measures enacted in China to contain it affected not only China but the whole world for at least two years. As I discussed in a previous post, a possible explanation was that the Chinese government believed that the country was under a biological attack.

The Chinese government had good reasons to think in that way. The idea of exterminating the Chinese people using biological weapons is more than one century old, and it may have been described for the first time by Jack London in his short story “The Unparalleled Invasion” in 1910. It was an outcome of the xenophobic climate of those times and of the perception of the “Yellow Peril” represented by China. An ugly story that was later turned on its head by Sax Rohmer with his “Fu Manchu” series (started in 1913) that depicted the Chinese as evil would-be exterminators of the Whites.

Given the current situation, we haven’t progressed too much from those times of distrust. But what are the origins of the conflict? It is a long story that goes back to Roman Imperial times, when Europe and China barely knew of each other’s existence but were nevertheless connected by a commercial road that spanned the whole of Eurasia: the Silk Road.

— The first commercial war

The Silk Road appeared in its complete form during the 2nd Century BCE. At that time, the Romans were creating their empire on the basis of the gold and silver that they obtained from their mines in Northern Spain. Precious metals were used as currency by the government to pay for state expenses and then recovered through taxes. A nearly perfect arrangement that led to the Roman Empire to grow to include a large swat of Eastern Eurasia and Northern Africa.

However, the Romans rapidly developed a taste for luxury goods made in China and imported through the Silk Road: silk, spices, porcelain, textiles, and more. The need to pay for these goods in gold and silver created an enormous problem for the Roman economy. The Chinese showed no interest in Roman products, so the Roman gold went to China and stayed there. The empire was bleeding out gold that could only be replaced by mining. But mines are not infinite.

Around the 1st century CE, the Roman mines of precious metals started showing signs of depletion. By the 2nd and 3rd centuries, the gold depletion problem had become serious, as shown by the continuous debasing of the Roman currency. The Romans couldn’t even imagine recovering their gold by sending their legions to attack China, as they would do when they were in debt with a neighboring state. So, the only option left for the Empire was to disappear. Which it did by the 5th century CE. You could say that China had strangled Rome using a very long leash called the “Silk Road,” but it is likely that the Chinese had no idea of what was happening on the other side of the Eurasian continent.

— The second commercial war

The same scheme reappeared in the 18th century when Europeans again acquired a taste for goods made in China. The Chinese obliged, assembling an early industrial system that exported goods worldwide. By the late 18th century, the demand for Chinese luxury goods like silk, porcelain, and tea created a trade deficit for Britain and other European states.

Just as at the times of the Roman Empire, the Chinese didn’t seem to be especially interested in European products, and they wanted to be paid in precious metals. That created a new commercial imbalance. This time, however, the Europeans had no intention of letting their silver disappear into China.

First, the British developed a product that could find a market in China: opium. The Chinese had a long history of opium consumption. As a recreational drug, it never caused large problems, although the government often tried to forbid or reduce its use. However, the British expanded the cultivation of opium in the regions they controlled in India; then they shipped it to China at low prices to encourage consumption. By the 1830s, millions of Chinese were addicted to opium. The flow of cheap opium reversed the trade surplus, with China now running out of silver.

The Chinese government attempted to suppress the opium trade. Tensions escalated, and in 1839, the British attacked China, defeated the Chinese army, and forced the Chinese government to sign the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842. The treaty granted the British control over Hong Kong and opened several Chinese ports to foreign trade, including opium.

A second Opium War erupted in 1856 when the Chinese government tried again to crack down on the opium trade. This time, other Western powers, including France and the United States, joined the British. The Allied forces launched attacks on Chinese cities and eventually captured Beijing. The Treaty of Tientsin was signed in 1858, further expanding foreign trade and granting additional concessions to the Western powers. It also led to a further expansion of opium use in China.

The Chinese describe the invasions as the start of “the century of humiliation.” Racism toward the Chinese became common in the Western Hemisphere and the anti-Chinese sentiment ran strong during the early 20th century, as the idea of exterminating disliked people remained popular in the West. The 20th century saw a new clash of Western and Chinese armies when the US and China fought each other in Korea in 1950-1953, even though contrasting commercial interests did not fuel this war.

— The third commercial war

As usual, history tends to repeat itself, and the 21st century is seeing again a commercial unbalance of the West with China, with threats of military actions from the West. Recovering from the disastrous events of WW2, the Chinese now have an industrial powerhouse that can steamroll, in commercial terms, anything that the Western industry can put together. One can mention the automotive industry, with the Chinese entering the market with their advanced electric vehicles. The American Tesla remains a leader in the field, but by now, the European car industry looks like it were stuck to the steam engine. It is perfectly possible that we’ll see the European automotive industry disappear or, at best, remain alive in a zombie-like existence as subcontractors of Chinese companies.

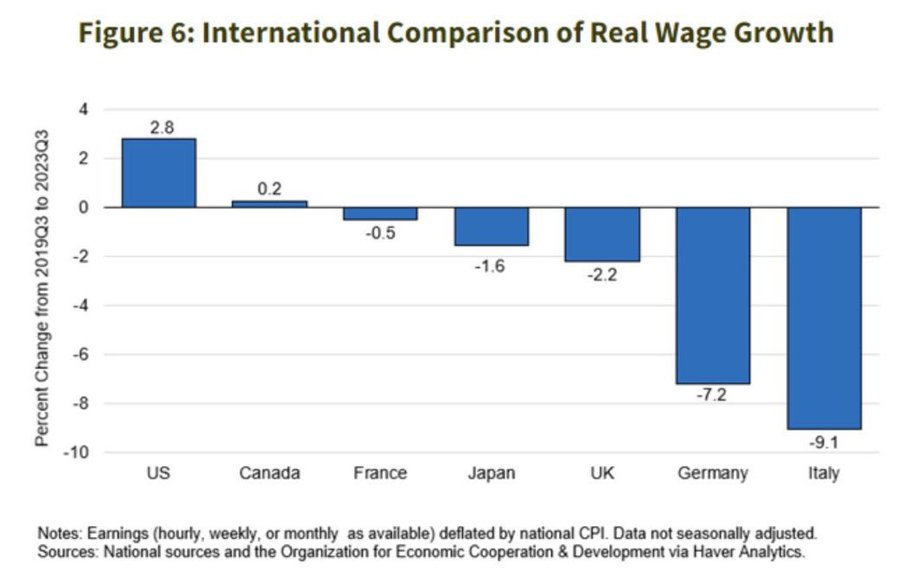

The problem is not just with cars. If you have contacts with the industrial world in Europe, you’ll see that a somber mood is common. Europe is engaged in a war against Russia, and its economy is being squeezed by the lack of natural resources that must be imported at high prices. To say nothing about the effect of the economic sanctions against Russia that backfired badly, depriving Western Europe of a traditional market and a source of cheap energy. The figure below shows some of the consequences. I can tell you, from Italy, that the situation is worse than it seems from this image.

The Europeans have cornered themselves in a situation where they cannot compete with China, just like the Ancient Roman Empire did long ago. The problem does not affect the US, which controls the world’s financial system by establishing the dollar as the world’s currency. In addition, the US is relatively safe from high energy costs because of its productive burst of fossil fuels from shales. However, the commercial imbalance remains, and shale oil production cannot last forever. Then, the dollar may be displaced from its central position by the rise of other currencies, such as the Chinese Renminbi. Soon, the US could find itself unable to face the competition from China in the international market.

It is hard to think that the US could find an equivalent to the solution that the British found in the early 1800s, shipping opium to China to redress the commercial imbalance. Not that there are no health-destroying products that the US could export to China, including, for instance, hormone-filled hamburgers. But it is unlikely that the Chinese would fall again into the same trap. History repeats, but not always.

The military solution remains a possibility, and it is often flouted by American politicians. That explains the war drums we hear nowadays. But modern China has a much stronger military system than the old Chinese Empire and Western forces look in many ways obsolete because of their expensive and vulnerable carrier groups based on 80-year-old strategies. History might repeat itself with carriers playing the role of the Polish cavalry and drones that of German tanks.

In the background, there is the growing idea of the “Belt and Road” initiative; in many ways, a new version of the Silk Road. It would link the whole of Eurasia into a giant economic zone. It could do what the ancient Silk Road never could do: weld the Eurasian states into a single political entity: a Eurasian Empire. You can see that as a dream or nightmare, but history teaches us that what must happen usually does.

But history does not necessarily condemn China and the West to fight each other. Who knows? They might learn how to live in peace.

Trying to make sense of geopolitical tensions between the West and China in the 2020s without mentioning the CCP, Taiwan, TSMC, advanced semiconductor manufacturing or AI is about as credible as trying to make sense of the geopolitical situation in Iran in the 1970s without mentioning the CIA or Islam or explaining the Gulf Wars of the 90s without any reference to oil.

The Belt and Road initiative is not the Silk Road. It involves the building of new infrastructure, but it is also a projection of soft power, largely through finance, to build a multi-national coalition to rival that of the US-led order.

On a "rise of the rest" level, this is a noble aim, but one of the factors that has prevented it from achieving its intended ambition is entrenched traditions of kleptocracy in the countries China is trying to build up. China makes loans for the completion of ports and other infrastructure, the money disappears into Swiss Bank Accounts, Bitcoin, overpriced "art" and other money-hiding mechanisms, and the infrastructure projects languish in a half-built state. Now China has pulled back on the endless flow of money to places like Sri Lanka, Suriname, and Zambia.

The West couldn't find anything that China was willing to import to acheive something approaching trade equilibrium. China would rather manufacture everything "in house" often by ignoring patents and through industrial espionage. But China found a way to empty its own coffers by trying to finance the build-out of a modern trade network without first figuring out how to make sure the money they put up actually went to build infrastructure and not enrich corrupt local officials.

Also, the wealthy Chinese elite are doing everything they can to get their money out of China. Western (including Australian) real estate is a popular place to park Chinese wealth to put it out of the reach of the CCP, but it's not the only path by which wealth is now fleeing China.

Dragon Blade is a nice film with a lot of interesting and inspiring ideas, great propaganda for the Chinese selling their rulership as "first among equals"...

We must distinguish a lot looking at China, we have an "imperial history" and a parallel history of different ethnicities and commercial ventures inside the empire. The Chinese empire had fallen quite a lot of times, for sure once every change in "dynasty", from invasions from the outside or under the weight of internal corruption, but China is HUGE so almost never happened that all different provinces and ethnicities get in distress at the same time and any "imperial power" have little problem eve if corrupt and incompetent to respond at localized distresses using the might of the other provinces.

Took quite a lot to break the empire, but the seeds were there, a perfect detention cell and wealth pump feeding a ruling elite necessary, but that didn't need real skills to function immobile and immutable and ferociously and aggressively resisting to changes.

Chinese are merchants and mercantilist, all Asia is dotted from Chinese enclaves many centuries old, but mercantilism (as pure capitalism) is an ancillary economy depending on an "empire" (state or similar) as "buyer of last resource" because maximizing return of investments kill buyers as it is doing today:

- killing external buyers-

-dumping products on markets underpriced (internal overcapacity) deindustrializing other "partners"

-currency manipulation, creating products externally cheap but internally profitable

-investing in infrastructural projects in other countries realized by Chinese industries, creating a debit trap (https://www.cigionline.org/articles/beijings-top-down-foreign-investment-model-is-roiling-african-economies/)

-killing internal market-

-workers feeling overtaxed for no returns (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tang_ping , http://chinascope.org/archives/31432)

-social mobility perceived as based on corruption and nepotism

-rapid formation of huge conglomerates and decline of small and middle-sized economic actors (big have lobbing power)

-collapsing internal house market, important because was the Chinese "retirement plan" for a huge share of population

-birthrate free-fall indicating huge internal social stress

This is not a Chinese only sin, Germany too and others are walking this path, this is the effect of mercantilism because it's a system of wealth pump based on external export obtained trough internal market compression, quite effective if you find "others" open to be spoiled!

Empires fall by implosion from internal inconsistencies and power concentration or simply by the entropic disease, their "death" is reached when become so unchanging and immutable that it can not react to new stimuli: when a new situation or event manifest the solution is more of the ones previously used because even if not efficient is the one that preserve the status quo!

Personally, I suspect that Roman Empire didn't "bleed dry" to China because we didn't see a corresponding "empowerment" of Chinese economy, Roman fell under their own weight as today we see the American Empire falling under its own weight and not bleeding dried by other (as happened to URSS).

American Empire is today pivotal to economy of other nations as buyer, sanctioning is his most powerful weapon because of this! (https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2024/06/24/bank-of-china-halts-payments-with-sanctioned-russian-lenders-kommersant-a85503)

Empire is the "Buyer of Last Resort" so mercantile economies are always depending on his whim, be free from empire need a for of autarchy and self-reliance....