… Conan, destined to wear the jeweled crown

of Aquilonia, upon a troubled brow.

It is I, his chronicler, who, alone, can tell you his saga.

After that dragons are slain, enemies defeated, and new kings enthroned, only memories remain. Then, a saga of heroes, gods, and monsters emerges. It is happening with the story of the tiny dragon called SARS-COV2, now crossing the border of the twilight zone, fading into Dreamtime. Forgotten by some, fondly remembered by others, and twisted into unrecognizable forms by many, it is becoming a saga. It reminds us of events of the past and tells us something about ourselves and how we may repeat the same errors over and over.

The COVID-19 epidemic was a huge event that reverberated across the world. We had enormous trouble understanding it while it was happening, and even now, it is nearly impossible to disentangle the events, twisted and transmogrified in ways that suit the political views of one or another teller of the story.

Four years after the start of the story, I am trying here to examine its origins from the viewpoint of a resident of Italy, the place where the virus first arrived in Europe. Italy was also the place where lockdowns and other “non-pharmaceutical interventions” (NPIs) at the level of an entire country were enacted for the first time in history. I did my best to maintain an open mind while remaining close to what we know with reasonable certainty. But I recognize that some things about this story will always remain obscure to us.

On the whole, I believe that there was no single global conspiracy behind the COVID story. It was mostly the result of a combination of social, economic, and political factors that coalesced to form a single interpretation that dominated the public view (the “memesphere”). But take my thoughts with appropriate caution. I just hope that in this post you’ll find something you hadn’t noticed before or an interpretation you had not considered.

1. The Military Origins of the Covid Story

Epidemics happened many times in the past. So, when a new respiratory virus appeared in the city of Wuhan in China in January 2020, it was not an unusual event even though the initial reports described it as aggressive and dangerous. What was unusual was the reaction of the Chinese government.

Quarantines are a normal reaction to epidemics, but it had never happened in history that an entire city was subjected to a strict quarantine of all inhabitants, no matter whether they were sane or sick. Indeed, a new term, “lockdown,” was later used for this action. In addition, it was the first case that saw extensive applications of NPIs, restrictions such as social distancing, travel bans, shutting down schools and economic activities, sanitizing everything, and more.

We’ll probably never know what led the Chinese government to react the way it did. However, it is difficult to interpret their behavior as a reaction to a natural virus. What may have pushed them to act was the perception that the virus was something much more dangerous. A bioweapon, either leaked from a research lab or purposefully spread by an enemy as an act of war. For obvious reasons, the Chinese government always denied the idea of a lab leak, but it is a perfectly possible hypothesis.

That a government could react in that way is not surprising if you remember how, in 2003, the US government reacted to a perceived bioweapon threat from Iraq by launching a full-scale invasion. In that case, the threat turned out to be imaginary, and the invasion clearly was planned for other purposes. However, the fact remains that the authorities and the public saw the threat as plausible.

The fear of biological weapons is a recent development. Up to a few decades ago, natural pathogens were not considered effective weapons. They were slow, impossible to aim at a specific target, and always carried the risk of backfiring. Indeed, the only known case in modern history of a biological attack having caused victims is the “Anthrax Scare” that swept the US after the attacks on the World Trade Center in 2001. Despite the known lethality of the anthrax bacterium, it only caused a grand total of 17 victims.

However, by the 1990s, genetic engineering technologies made it possible to hack the DNA of biological creatures and, in principle, to create more deadly viral and bacterial strains (a procedure called “gain of function”). Not only that, but by creating a new pathogen in a laboratory, the attackers could manufacture a specific vaccine in advance to protect their population. That would make sure that only the enemy population would be targeted. As it was said of the Maxim guns in ancient colonial warfare, “We have them, and they don’t.”

In the 2000s, the concept of "biological warfare" became part of strategic planning worldwide. Up until then, the accepted wisdom for facing an epidemic was a soft approach: letting the germs run in the population to reach natural "herd immunity." For instance, in a 2007 review, the authors stated that "There are no historical observations or scientific studies that support the confinement by quarantine of groups of possibly infected people for extended periods in order to slow the spread of influenza."

But a bioweapon attack is supposed to be on another realm of lethality, able to cripple the functioning of an entire state. Herd immunity is not enough to counter this kind of threat. The pathogen has to be stopped fast to allow the defenders to identify it, determine its genetic code, and then develop a vaccine. In the 2000s, several documents advocated a more aggressive attitude toward epidemics. The possibility of a biological attack was mentioned only in some cases, but it clearly was the origin of these proposals. An example is the study prepared by the Department of Homeland Security in 2006. Another came from the Rockefeller Foundation in 2010. Possibly the most influential one was a report written in 2007 by Rajeev Venkayya for the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It examined a hypothetical outbreak of a viral infection that would kill two million people in the United States if left to run undisturbed.

Venkayya mainly based his considerations on a paper by Ferguson’s group in London. That study was a classic academic exercise in irrelevancy, but whereas there are plenty of irrelevant academic papers (probably a large majority), they can become dangerous if taken seriously. Venkayya took some theoretical hypotheses from Ferguson’s paper and turned them into real-world interventions. The result was a list of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) involving restrictions on the movement of people, closures of most activities, reduction of social contacts, and, for the first time, the concept of "flattening the curve."

The diagram above is taken from Venkayya’s report; it had a remarkable influence on how governments reacted to the COVID-19 epidemic more than ten years later.

In a previous post, I criticized Venkayya’s diagram, defining it as “the worst model in history.” Its main problems are that it does not indicate whether your NPIs are working, nor does it provide an “exit strategy” to stop the intervention when it is no longer necessary. In addition, it is supposed that the interventions started at “zero time” — when the virus has just appeared. These problems plagued the reaction to the COVID outburst from the beginning: measurements were abundant, but there was no good framework to analyze them.

The measures taken by the Chinese government were similar to those proposed by Venkayya, even though the Chinese authorities surely had their own strategic plans. The initial results seemed to validate the idea of NPIs, and lockdowns. Here are the results of the first epidemic cycle in China.

Apart from a glitch, probably due to some change in the measured area or conditions, the number of cases moved along a typical “bell-shaped” epidemic curve that started in January 2020 and went to zero after about two months.

At the time, this result was seen as a great success. Don't forget that the initial reports had described an extremely deadly virus that could cause tens of millions of victims. Instead, the deaths were reported to be about 5000 in total, surely an overestimation since not everyone who died “with” the SARS-Cov2 virus died “of” the virus. Out of a population of one billion and a half, the probability for an average Chinese citizen to die of (or with) Covid during 2020 was of the order of 2-3 in a million. It was effectively zero for everyone under 60.

But was this really a success of the containment policies? Or was it simply the result of the virus following its natural epidemic curve, being much less deadly than it had been feared? Whatever the case, it was a personal triumph for China's president, Xi Jinping. It was the start of a saga that would affect the whole world.

2. The virus arrives in Italy

By February 2020, the virus outbreak in China was news worldwide. The Western media overdramatized the story and lost no opportunity to slander China and its government. Westerners were treated with lurid photos of people dropping dead in the streets in Wuhan while, in the US, President Trump and many others spoke about the “Chinese virus.” The photo below was published in “The Guardian.” It had nothing to do with the virus outbreak but was presented as such.

The first cases of SARS-CoV-2 were detected in Italy in early February 2020 while the media scare campaign was in full swing. Whereas the Chinese may have feared being attacked by the West, now Westerners may have feared being under attack by the Chinese. It would have had to be a truly devious kind of attack because it started by hitting the attacker’s population. However, the Chinese are known to be devious and evil, as demonstrated by decades of Hollywood movies.

Italy was on the front lines of this perceived biological war, and the Italian government chose measures even more drastic than the Chinese ones. After some brief local lockdowns, the government enacted the first nationwide lockdown in history on 9 March 2020. Everyone in the whole country was supposed to stay home 24/24, leaving only for essential needs, such as getting food. In addition, all sorts of additional measures were enacted, including travel restrictions, school closures, and a ban on public gatherings.

The two government officers most responsible for these extreme measures were Giuseppe Conte, the Prime Minister, and Roberto Speranza, the Minister of Health. They were normally regarded as second-rate leaders, propelled to the positions they occupied by a combination of luck and shrewdness. Probably, it was a good definition because, four years later, they have all but disappeared from the political scene. You wouldn’t have expected people like them to take a momentous decision that changed the world’s history. Yet, they did.

A series of recently disclosed documents show that the lockdown decision was taken amid incredible confusion. People were pushing in one or another direction, some indifferent, some panicking, some trying to avoid damage for their activities, and others pushing to create damage to their competitors. It may be that Conte, Speranza, and other politicians just saw a chance to become the heroes of the story. Everyone loves dragon slayers.

We may also imagine external influences affecting the decision. Italy is a province of the Western Empire, and its government cannot make important decisions without the approval of its imperial masters. So, it may be that Italy was chosen as a test bed to study the effectiveness of strategies against bioweapon attacks, so far never experimented with in the real world. If the test were successful in Italy, the same strategy could be replicated in other Western countries. This is only a hypothesis, of course, but the events in Italy steered the whole world in an unexpected direction.

The Italian experiment was seen with interest, and perhaps surprise, also outside the Western sphere. China shipped medical personnel and equipment to Italy on March 14, just a few days after the start of the Italian lockdown. Officially, it was to help Italy contain the pandemic, but what could a total of nine medical staff do to help a country with 60 million inhabitants? It seems clear that the Chinese wanted hands-on data on the virus spreading in Italy. Shortly afterward, on March 22, the Russians sent their own sanitary expedition ostensibly to help Italy but surely also to collect data on the virus. Evidently, during this phase of the pandemic, everyone was suspicious of everyone else at the international level.

No matter who decided the Italian lockdown, they didn’t forget to accompany it with a massive propaganda operation. People were bombarded by daily bulletins with the number of victims of the day. The TV screens hosted solemn virologists dispensing their doom-and-gloom predictions. The procession of military trucks carrying the dead to incinerators is likely to become a classic in modern propaganda. In the figure, you see the “Bare di Bergamo” (the coffins of Bergamo) as the convoy appeared on TV. Still today, Italians may cite these coffins as proof of the deadliness of the pandemic.

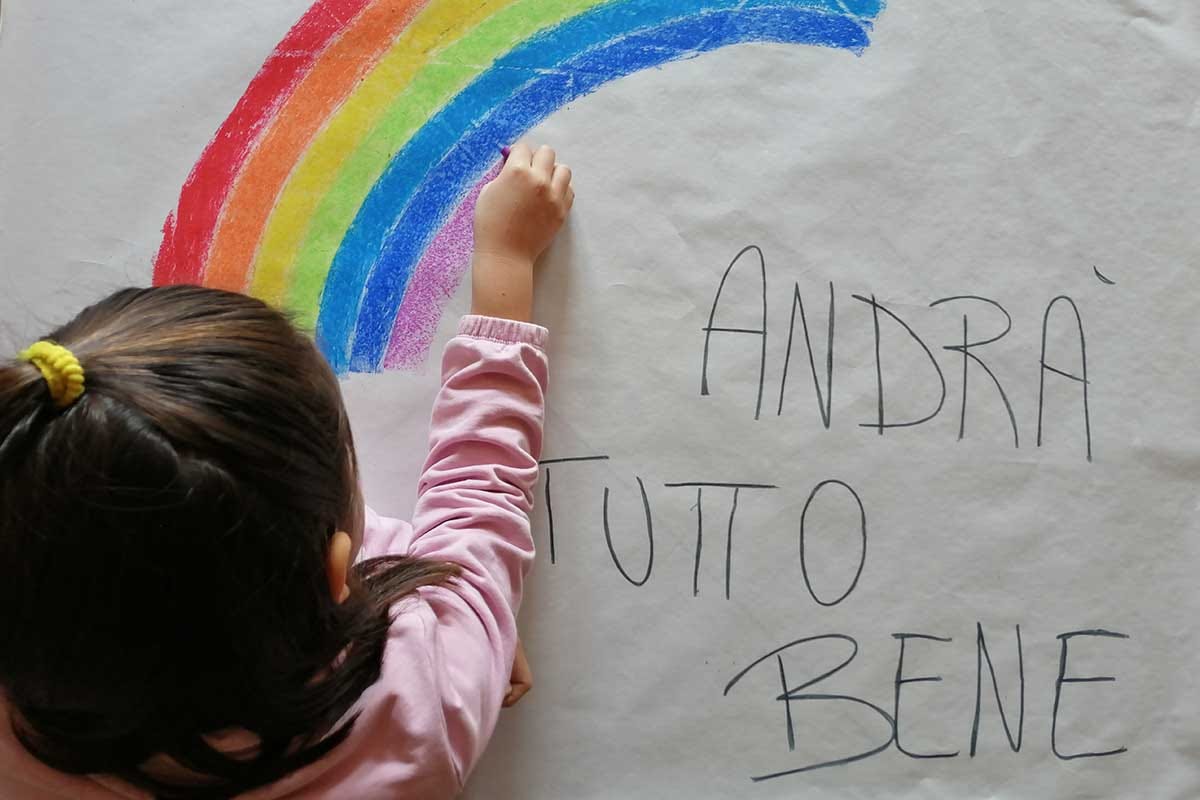

Propaganda also took a more positive approach. People were told that by staying home, they were doing something good, even noble. They were helping everyone, especially the elderly, avoid the deadly coronavirus infection. The propaganda insisted that the lockdown and the social distancing were only temporary measures, and then “we’ll embrace each other again.” And everything will be well (“andrà tutto bene”).

The success of this propaganda operation was remarkable. For a couple of weeks, Italy was an idyllic place where people enjoyed a vacation at home. Some used their free time to cook elaborate meals, set up home gyms, watch TV, and play video games. Remote working was welcomed as a liberation from the dreary routine of going to work every day. It was said, and it is probably true, that they expressed their joy by singing songs from their balconies.

Criticism of the lockdown and NPIs soon became politically unspeakable, and those who dared to express doubts were likely to be abused and insulted by their relatives, neighbors, and the media. And not just that: many received death threats. At least one doctor who was critical of the government’s policies committed suicide in 2021 because of the negative campaign against him. Those who tried to cheat were subject to general scorn and reprobation. Those who were seen outside their homes were reported to the police by their neighbors and hunted down using drones and helicopters.

The Italian example was followed by other countries. Germany went into lockdown on March 16th, France on March 17th, and Britain on March 24. In the US, President Trump asked for voluntary restraints on March 14th, and mandatory lockdowns were enacted in some US states. Soon, with a few exceptions, the whole Western world was applying the Italian recipe. Everywhere, the public accepted the lockdowns without major protests.

Unfortunately, as often happens, political success doesn’t imply success in the real world. Initially, the idea of “Squashing the curve” was meant to simply slow down the infection rate in order to avoid overloading the healthcare system, but it was implied that the epidemic would still run until the population could reach herd immunity. Soon, though, NPIs were repurposed in different terms. Staying home meant, for instance, saving the elderly (a slogan from Britain went as “Don’t kill granny!”). It was described as preventing the infection curve from “growing exponentially” and killing millions of people, maybe everyone. Finally, there came the idea that NPIs could eradicate the infection.

These lofty goals were incompatible with the way governments had initially sold the NPIs to the public. The innuendo was that they would not last long—maybe a few days, at most a few weeks. But the war on the virus had turned from a skirmish to a battle of annihilation. That implied it would last until the goal was reached, whatever the goal was, no matter how long it would take. And the goal could only be the impossible “Zero Covid” condition. Unfortunately, no matter how nice and smooth Venkayya’s curve looked, slaying the tiny Covid dragon turned out to be much more difficult than it had seemed at the beginning.

Here are the data for the development of infections in Italy (figure from “Our World in Data).

The start of the lockdown, on March 12th, didn’t have any effect on the curve. The number of new infections didn’t peak until March 27th, and the total number of active cases didn’t peak until April 20th. It was the normal behavior of an epidemic curve, but the government and most people in Italy seemed to think that, without NPIs, the curve would have grown much faster, even to infinity. The vagueness of the concept of “squashing the curve” was evident in this circumstance. Plenty of people took these data as evidence that the lockdown works, although with a delay of two weeks. What mysterious mechanism could lead to such a behavior was a question that wasn’t asked. and no one seemed to remember that the models of the original paper by Ferguson et al., the one that created the whole madness, clearly showed that the effects were expected to be immediate.

Even when, eventually, the number of infections started to decline, the NPIs were kept in place in Italy simply because there was no clear goal for what the action was supposed to obtain. As long as the testing showed that the virus was still detectable in the population, nobody would dare say that the restrictions should have been eased because, as everyone knew, otherwise the epidemic would restart growing “exponentially.” By May 2020, people had been locked inside their homes for more than two months, and they couldn’t take it anymore. The NPIs started being eased, although they were completely eliminated only by June 3rd, 2020, nearly three months after they were enacted.

With the virus slowly declining with the summer, as respiratory viruses typically do, the Italian lockdown was sold to the public as a success. In November 2020, the Minister of Health, Speranza, published a book titled "Why We Will Be Healed," personally taking credit for the eradication of the epidemic in Italy. The mood in other countries was the same, with politicians such as Matt Hancock and Dame Angela McLean in the UK, and probably many others in other countries, ready to “own the exit,” claiming they slew the Covid dragon. Some countries, such as New Zealand, claimed to have “eliminated Covid” by their strict measures. And, of course, China remained COVID-free after the apparently successful lockdown of Wuhan and its province. But things were soon to change.

3 . The Return of the Tiny Dragon

Respiratory viruses are known to subside in summer and reappear in winter. There was no reason to think that the SARS-Cov2 virus would be different, except for people thinking that the world really is what they think it should be (typical of politicians and of people who believe in government propaganda). In the winter of 2020, the number of COVID cases restarted growing in Italy, just like everywhere in the world. The figure below is from “Our World in Data.”

There was no reason why the return of the corona microdragon should have taken people by surprise, but it did. So much so that, in Italy, Mr. Speranza hastily removed his triumphal book from bookstores. It may also be that it was this return that cost Donald Trump the elections of November 2020 because he was attacked for having been “too soft” on the virus.

The restarting of the epidemic posed big problems to leaders. How could it be that the NPIs hadn’t squashed the curve? How about the zero COVID idea? And how could the Chinese have been so successful with their lockdown, whereas Europeans hadn’t? The simplest explanation was that the NPIs simply had a modest effect — if any, as various studies later revealed (see, for instance, a recent study). The infection curve might have simply followed its natural trajectory of growth and decline, oblivious to the antics of humans.

The problem was that when politicians make a mistake, they cannot admit it. That makes them grandmasters at the art of doubling down. And the public tends to reason in the same way or, at least, can be easily convinced by propaganda. So, it was said that NPIs had not succeeded in eradicating the epidemic not because they were a bad idea but because they had been poorly implemented. That provided an easy target for a hate campaign that started blaming “cheaters” for the return of the virus.

In Italy, during the summer of 2020, people had forgotten about the virus and did all the things people do to enjoy life during their vacations: having parties, going to restaurants, attending public events, and all that. Now, these wholly normal actions became sins against one’s social responsibility to keep the virus away. How it could be that the actions of people in August could affect the spread of the virus in November was not asked and not explained, but that was the way things were described. The cure for the failed lockdown was more and harsher lockdowns. It was a sort of divine punishment.

The winter of 2020-2021 was the golden age of lockdowns and the associated NPIs, accompanied by face masks, which were earlier described as useless but then became a salvific element of the fight. All sorts of quixotic regulations were implemented, often devised on the spur of the moment by politicians on a “power high” and then rubber-stamped by individual scientists and scientists’ committees, eager to please those who paid them. Italy acquired a checkered pattern of red zones, orange zones, and white zones, where you could or could not do certain things, such as travel beyond the city limits or eat in a restaurant. Plexiglass screens appeared everywhere even though, with the best of goodwill, the idea that they could stop a virus was equivalent to thinking that mosquitos could be stopped by the bars of a railroad crossing. Yet, the idea was accepted, and denying it rapidly became politically incorrect and censored by social media and the state media.

It was probably unavoidable: a typical feature of Western politics is that nothing can be done without framing it as fighting an enemy. The tiny corona dragon couldn’t be demonized in the same way as it can be done for human beings; it had no leaders, no army, no ideology, and it couldn’t even be seen. So, politicians found it expedient to create a new target among those people who criticized the “Science.” A resistance movement against NPIs started to develop, sometimes described with the term “anti-mask” or “anti-maskers.” In the US, it followed the traditional political frame, with the libertarian right opposing masks and lockdowns while the socially oriented left favoring them. The same division appeared in many Western countries. A break was developing in the fabric of society. It was growing, and it has not been mended even today.

3 . The time of vaccines.

From the beginning of 2021, the vaccination campaign against Covid-19 started worldwide. I will just briefly summarize this phase because Italy was not the first country to move in that direction, nor did it take special measures. However, it may be that the “nudging” campaign to convince people to vaccinate was more drastic and invasive in Italy than in other countries. A new government head, Mario Draghi, was named in February in place of Giuseppe Conte, perhaps with the idea that a more prestigious leader (Draghi had been the president of the European Central Bank) could be more effective in pushing vaccinations in Italy. Perhaps it was because it was believed that more dragons were needed to fight dragons (in Italian, “draghi” means “dragons”).

The vaccination campaign advanced in Italy through a series of restrictions and punishments against the unvaccinated. They were deprived of their salary and harassed in various ways by a campaign that depicted them as selfish and dangerous. They were even defined as “rats” by a fashionable TV virologist of the time and threatened to be kept locked down forever. On June 22, 2021, Mario Draghi publicly stated, “If you do not vaccinate, you get sick and die. And you kill others.” It was part of the way vaccines were sold to the public: they were supposed to stop the virus transmission and make the hated lockdowns unnecessary.

There was a problem, though. It soon became clear that vaccines didn’t stop the diffusion of the virus. In 2022, despite the success of the mass vaccination campaign, the number of cases in Italy went up to levels unseen before. That kept the fear of the virus alive, together with several NPIs, throughout 2022. Below, you see data for the prevalence of the virus in Italy

4. The Fading of the Pandemic

Fortunately, the mortality associated with the virus tended to go down with time. It might have been because of the vaccine had an effect in reducing mortality, or simply because of the tendency of viruses to evolve into less lethal forms. In any case, the worries about the pandemic slowly faded in the public opinion in Italy. There never was an official statement that “it is over,” and some people still maintain it is not. But, in practice, it is. If you look at the figure, you see a return of the virus in the winter of 2023-2024 of the same order of magnitude as the first outburst in 2020. However, the reaction in 2020 was panic, whereas in 2024, it was yawns.

Even more impressive was what happened in China. Up to 2022, the Chinese were very proud of their apparent success in containing the pandemic, convinced that their superior discipline and sense of duty had saved them from the sad destiny now befalling those riotous and unruly Westerners. But in 2022, the virus started spreading in the Southern areas of the country despite universal vaccinations, face masks everywhere, and a new, drastic lockdown enacted by the authorities.

Initially, the Chinese were bellicose: President Xi-Jinping said, “We have won the battle to defend Wuhan, and we will certainly be able to win the battle to defend Shanghai." However, with cases spreading sky-high, it was soon clear that it was a lost battle and that the Chinese people, despite their discipline, couldn’t take it much longer. Eventually, the Chinese government decided that the best way to avoid finding the virus was to stop looking for it. They did exactly that. Here are the results from Worldometer:

In this dragonish battle, the Chinese dragon had found an easy way to get rid of the Corona dragon: what you don’t see does not exist. The epidemic was officially over in China.

5. Conclusion

Nowadays, the Covid pandemic seems to be a thing of the past, with the virus becoming tame or, at least, not considered a threat anymore. The total number of Covid deaths over the past four years is estimated at about 7 million worldwide, less than 0.1% of the world’s population. And consider that it is almost certainly an overestimation because not everyone who died with Covid died of Covid. It was nothing even remotely comparable to the great plagues of the past if you think that the Black Death in Europe is said to have killed about 30% of the population, or perhaps more.

Nevertheless, everywhere, the public seems to be still confused and unable to take a coherent position about the pandemic. In Italy, a recent poll shows that nearly 50% of people see COVID-19 as nothing more than seasonal influenza, and practically nobody wants to vaccinate for the virus's recent return.

At the same time, the poll shows that a majority is still favorable to mandatory laws to enforce new lockdowns and mask-wearing in public spaces. But in Italy, almost no one, except a few diehard ones, wears masks in public. Judging from the behavior of the crowds everywhere, it seems that no one cares anymore about “social distancing” or other NPIs that were so fashionable just a couple of years ago.

How was it that the world reacted (and may still react) with such extreme measures to a threat that, seen today, was much exaggerated? Surely, lobbies and economic interests benefited from the pandemic, and plenty of people obtained personal economic or political advantages from it. Overall, though, I tend to think that the pandemic was not planned in advance. In other words, there was no group of dark figures collecting in a smoke-filled room (maybe in the basement of Bill Gates’s mansion) to discuss an evil plan to start the pandemic.

I think the best way to understand this story is that it was a typical "feedback cascade." It is the great power of ideas, which we also call “memes.” Memes are snippets of thought that may go viral in the memesphere, just like biological viruses do in a population. People passed memes to each other during the pandemic, just as they passed real viruses. Then, the whole train wreck was created by a convergence of parallel memes from politicians, decision-makers, industrial lobbies, and even simple citizens, most of them truly convinced that they were doing the right thing that just happened to coincide with their personal interests.

Many ordinary people, and probably even their leaders, fully believed the memes that the government's propaganda machine was pushing, and they did things that were positively harming them physically, socially, and economically. They still do; memes are resilient. Daniel Dennett said that "a human being is an ape infested with memes," and the COVID story shows that it is true. It is our tendency to believe in myths and fables that put us in trouble, as it has done many times in the past. It remains to be seen what much more evil and violent memes can do to us if they spread. And it seems that we have plenty of them spreading right now.

Roberto Speranza was not a member of M5S party, but LEU party.

I agree whole-heartedly that the whole thing was a collective meme-happening.

I'm no fan of "conspiracy theories," instead, thinking that people all do what they perceive to be their best interest. I think Taylor Swift probably has more influence in such things than Bill Gates.

But to me, the more interesting thing is (as I have seen elsewhere) to lay the COVID-restriction graphs on top of the contemporaneous economic and CO2 graphs. It appears that the draconian "lock downs" achieved — for far too short a time — precisely what we need to do to get our climate and non-renewable resource hunger somewhat under control!

Yes, everyone was inconvenienced. Some more than others — small businesses, performing arts, personal services, etc. — but it seems a rather small price to pay for the mere survival of future generations.

If I were king of the world, I'd bring back the restrictions as a way of de-growthing the tremendous harm humans are having on their own habitat.

This is not mere conjecture, as you assert the COVID lock-downs were. But thanks to those lock-downs, we have the proof that such things are actually the only things that have EVER worked against CO2 and energy resource depletion!

Could the real lesson not be that "flattening the curve" of infections didn't work, but that "flattening the curve" of the Seneca Effect did? Wouldn't it be worth it to slide graciously down the back-side of a bell curve, rather than (as we presently seem to be doing) jumping off the impending poly-crisis cliff?