What if Predicting Collapse Hastens Collapse?

Why Oedipus and Cassandra Both Failed

Oedipus and Cassandra are both inhabitants of the mysterious region we call “dreamtime,” so we may imagine that they could have met somewhere, even though they belong to different mythical cycles. They embody the two possible ways we have to react to the future. Both knew they were facing a dismal destiny: Oedipus thought he could escape it by his actions, but he made it worse. Cassandra did nothing, and that sealed her fate. In our times, we oscillate between cornucopians, who think that we can avoid collapse by being smart enough, and doomers, who think there is nothing that can be done. Both attitudes ensure collapse and may make it worse. As in ancient Greek Myths, there seems to be no space for middle ways in the current debate.

It is a tradition that, at the end of the year, people who discuss political and economic matters (like me) try to make predictions for the year to come. Modern predictors (myself included) have a generally poor record, especially for long-term predictions. Yet, we all indulge in this hobby, one way or another. We are born predictors.

The current debate sees two camps facing each other: the catastrophists and the cornucopians. The first group sees our civilization brought down by a combination of pollution, resource depletion, or overpopulation. The second sees technological progress breaking through all physical barriers and leading humankind to keep growing in power and numbers.

It is remarkable how this debate is polarized. Both sides see no shades of grey. The ancient myths of Cassandra and Oedipus give us a nice illustration of these two extremes. Oedipus was told by an oracle that he would kill his father and marry his mother. That led him to take a series of actions that led him, indeed, to kill his father and marry his mother — albeit unknowingly. Cassandra foresaw her own violent death, but did nothing to avoid finding herself in the place where she knew she would be killed.

Reading these ancient stories, one is tempted to tell an aside to Oedipus: if you have been told by a reputable oracle that you’ll kill your father, be advised to exercise some caution before picking up a quarrel with someone old enough that he could be your father, And, as an aside to Cassandra, if you know that Clytemnestra, Agamemnon’s wife, will run after you with a battle axe, why aren’t you wearing at least a helmet?

Unfortunately, today, taking extreme positions seems to be commonplace in the debate about our future. Those of us who try to strike a balance between doomerism and cornucopianism are normally seen as traitors from both extremes of the spectrum of the debate. Yet, there is space for a view that considers that neither the return to the Stone Age nor the colonization of Mars are just around the corner. A viewpoint that sees collapse not as an event but as a process. We may not be able to avoid it completely, but we can manage it, soften it, and prepare a return from a decline that doesn’t necessarily have to arrive at the very bottom of the chasm.

Think in mythological terms; always a window to see how the human mind works. If we are Cassandrian catastrophists, we will do nothing to avoid collapse, and we’ll experience it in full. On the contrary, if we are Oedipian cornucopians, we’ll consume more resources and produce more pollution, accelerating collapse, and making it worse. In more practical terms, if you oppose renewable energy because you are convinced it doesn’t work, you are a Cassandrian. And if you oppose it because you think that nuclear fusion is just around the corner, you are an Oedipian. In both cases, you are courting catastrophe.

If we want to stay with the mythological metaphor, we could think of Odysseus, who always chose the safest option. Navigating through the Strait of Messina, he had to choose between the six-headed monster Scylla (who snatches sailors) and the whirlpool Charybdis (which swallows ships). Odysseus chose to sail closer to Scylla, sacrificing a few men, but saving the ship. In our modern case, if we mange the transtion prperly, we won’t need to have anyone killed, but we need to throw overboard some of the things we take for granted. Economic growth, for instamce.

In the following, I sketch a System Dynamics model that can give us some idea of what to expect. It is a “mind sized” model according to a definition by Seymour Papert, that I proposed as a way of creating useful system dynamics models. Mind sized models can help us to orient ourselves in a continuously changing world. So, don’t prophecies. Mind sized models don’t give us exact dates (Troy will fall on the tenth year of siege), nor certainties (Oedipus will marry his mother). The world always changes, and we must adapt to it, flexibility is the key.

The only certain thing that models tell us with is that if we don’t prepare ourselves in advance by working on the transition to renewable energy, things might get bleak, indeed. And we may hasten the catastrophe by taking extreme positions.

_______________________________________________________________

The Energy Transition in Mind-Sized System Dynamics Models: Four Scenarios from Collapse to Abundance

by Ugo Bardi

The Club of Rome. Winterthur, Switzerland

ugo.bardi@gmail.com

Introduction

Can we model the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy in a way that captures both the collapse dynamics of resource depletion and the potential for a sustainable energy future? This post presents a simple extension of the Single-Cycle Lotka-Volterra (SCLV) model that treats fossil and renewable energy systems as two independent capital stocks. The model was created in view of a “mind sized” approach proposed by Seymour Papert in 1980. To maintain the model simple, the two stocks (fossil-generated capital and renewable-generated capital) were treated as independent from each other. This is, obviously, an approximation. Renewables could not grow during the first stages of their development without an apport of energy from fossil fuels. But after they start growing, they will eventually grow on the supply of the energy they generate. So, this is a reasonable approximation for the purpose of this study.

Note also that I assume renewables are truly renewable, not simply "rebuildable" as some authors claim—a poorly defined term that adds unnecessary confusion. Modern studies indicate that the latest generation of renewable technologies (photovoltaic and wind) have EROIs (Energy Return On Energy Invested) much larger than one, and, at present, superior to the EROI for most fossil technologies. It means they can be rebuilt infinite times (at least as long as sunlight arrives on Earth). It is not impossible that the expansion of renewable technologies will encounter a bottleneck in the form of the need for mineral resources that will not be available in sufficient amounts. But, at present, no such bottleneck appears to be insurmountable, at least in terms of maintaining a large renewable producing infrastructure that can use internally recycled materials.

The Model

We model two separate capital stocks, assumed to be the defining factor of the entity called “civilization.” In this simple approach we do not consider other elements, such as population and pollution, assuming that the availability of energy at a high energy return (EROI) is what makes society function.

C_fossil: Capital operating on finite fossil fuel resources

C_renew: Capital operating on renewable energy (solar, wind, etc.)

The total capital is simply: C_total = C_fossil + C_renew

The Equations

The fossil system follows the classic SCLV dynamics. It is a simple modification of the well known rabbits/foxes models, where rabbits are supposed to be sterile, hence a non-renewable resource for foxes. This model generates a single “bell shaped” curve for energy production and also for capital accumulation. It is the basis of the well known “Hubbert Model” for fossil fuel production. The SCLV equations are:

dR/dt = -k₁ · R · C_fossil

dC_fossil/dt = k₂ · R · C_fossil - k₃ · C_fossil

Where:

R = remaining fossil fuel resources

k₁ = resource consumption rate

k₂ = capital growth efficiency from fossil resources

k₃ = fossil capital depreciation rate

The renewable system follows logistic growth with depreciation:

dC_renew/dt = k₁_renew · C_renew · (1 - C_renew/L) - k₂_renew · C_renew

Where:

k₁_renew = renewable capital growth rate

L = carrying capacity (maximum sustainable renewable capital)

k₂_renew = renewable capital depreciation rate

The renewable capital reaches an equilibrium at:

C_renew_eq = L · (1 - k₂_renew / k₁_renew)

This equilibrium represents the sustainable economy level that can be maintained indefinitely on renewable energy.

Key Parameters

The model has a few critical parameters that determine the shape of the transition:

L (carrying capacity): How much capital can the renewable energy system ultimately support?

k₁_renew (growth rate): How fast can we build renewable infrastructure?

k₂_renew (depreciation rate): How quickly does renewable infrastructure need replacement?

The ratio of these parameters determines both the final equilibrium level and how smooth the transition will be.

Base Case Parameters

For all scenarios, we use these fossil fuel parameters (representing a classic Seneca collapse):

k₁ = 0.01

k₂ = 0.005

k₃ = 0.7

R₀ = 1000 (initial resources)

C_fossil_0 = 10 (initial fossil capital)

These produce a peak fossil capital around 302 at t ≈ 1.3, followed by collapse.

For renewables, we always start small:

C_renew_0 = 1 (renewables just getting started)

And we vary k₁_renew and L to explore different scenarios.

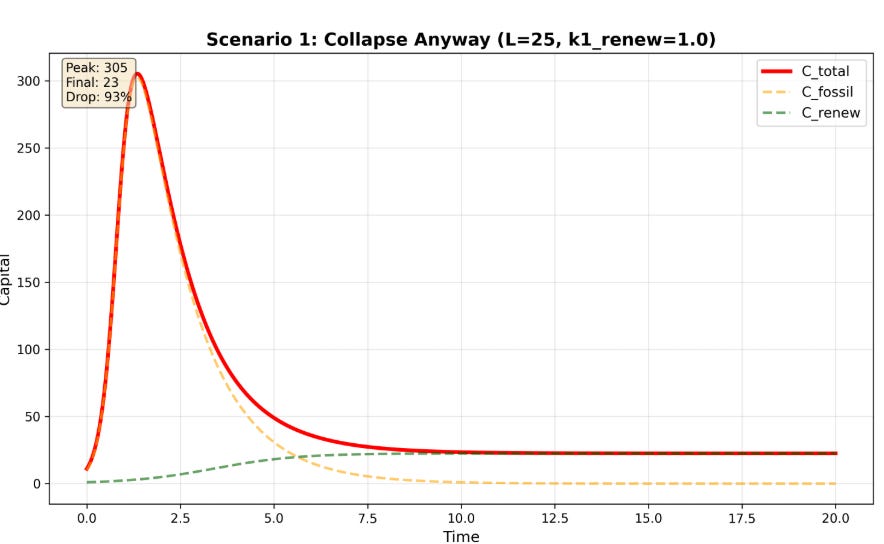

Scenario 1: “Collapse Anyway” - Slow Renewable Growth

Parameters:

k₁_renew = 1.0

k₂_renew = 0.1

L = 25

Results:

C_total peaks at 306

Drops dramatically to equilibrium at about 25

Final capital is less than 10% of peak

C_renew_eq = 25 × (1 - 0.1/1.0) = 22.5

This is the pessimistic scenario: renewables grow too slowly and can’t support as much capital as the fossil system did at its peak. We get the classic Seneca cliff - rapid growth on fossil fuels, followed by a brutal collapse that renewable energy can’t fully compensate for. Some kind of civilization survives, but at a much diminished level.

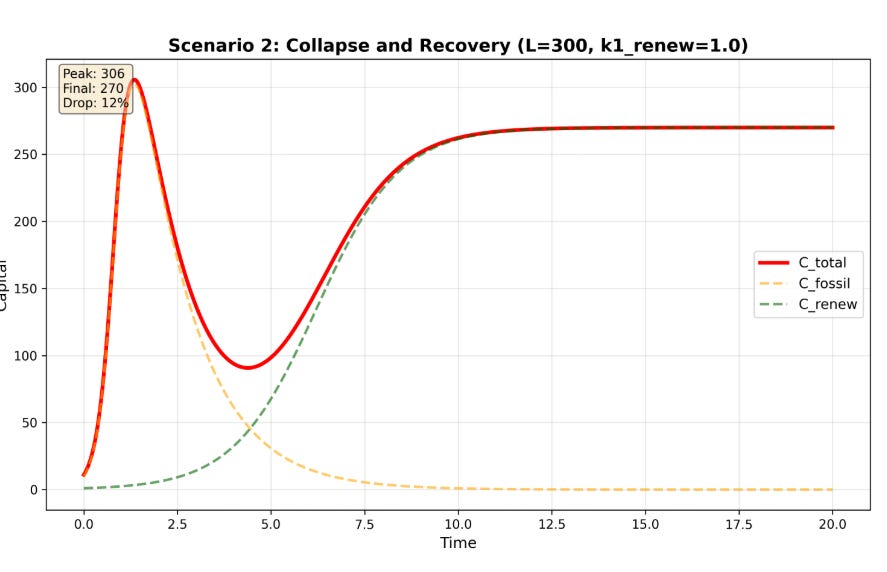

Scenario 2: “Collapse and Recovery”

Parameters:

k₁_renew = 1.0

k₂_renew = 0.1

L = 300

Results:

C_total peaks at 306

Drops to equilibrium at 270

Final capital is 88% of peak

C_renew_eq = 300 × (1 - 0.1/1.0) = 270

Here renewable infrastructure can ultimately support nearly as much capital as fossil fuels did. There’s still a dip during the transition (from 306 to 270), but it’s manageable - about 12% decline. This represents a challenging but survivable transition.

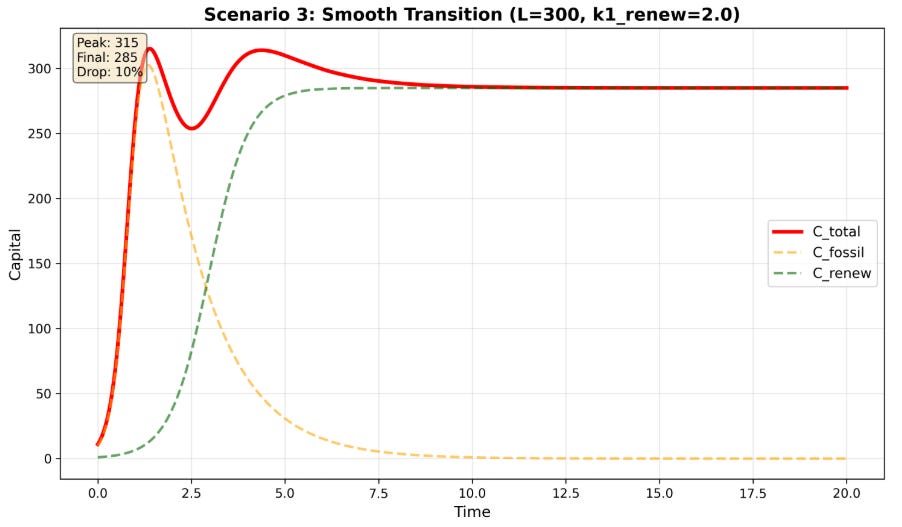

Scenario 3: “Smooth Transition” - Fast Renewable Growth

Parameters:

k₁_renew = 2.0

k₂_renew = 0.1

L = 300

Results:

C_total peaks at 315 (slightly above fossil peak)

Drops to equilibrium at 285

Final capital is 90% of peak

Only a 10% dip during transition

C_renew_eq = 300 × (1 - 0.1/2.0) = 285

This is the balanced scenario: renewable infrastructure gets built quickly enough (k₁_renew = 2.0) that it’s already substantial while fossil capital is still high. The total capital actually overshoots slightly (315 vs 302 fossil peak) because both systems are operating simultaneously for a brief period. Then there’s a gentle decline to a stable, sustainable level at 285.

This represents an aggressive but realistic renewable energy buildout - the kind of trajectory we’d need to minimize disruption.

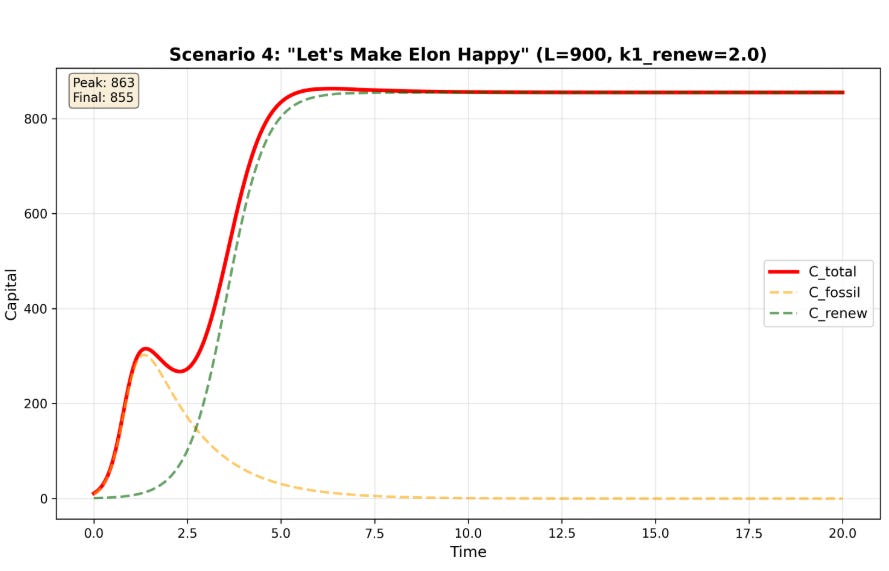

Scenario 4: “Let’s Make Elon Happy” - Renewable Abundance

Parameters:

k₁_renew = 2.0

k₂_renew = 0.1

L = 900 (three times the fossil peak!)

Results:

C_total peaks early around 305

Grows continuously as renewables ramp up

Reaches 855 by t = 20

Final equilibrium at 900 × (1 - 0.1/2.0) = 855

This is the techno-optimist dream: renewable energy infrastructure can ultimately support far MORE capital than fossil fuels ever did. Perhaps because it’s more distributed, more efficient, or unlocks new possibilities.

In this scenario, the “collapse” is barely visible - just a brief plateau around t = 2-6 as fossil capital declines and renewable capital accelerates. By t = 10, total capital has already exceeded the fossil peak and continues climbing to nearly triple the original maximum.

This would represent a genuine energy transition leading to abundance - Tesla’s vision of electrifying everything, SpaceX powered by solar, limitless clean energy enabling expansion into space, etc.

Discussion: Four Futures

These five scenarios span a wide range of possibilities:

Collapse Anyway (L=25, slow growth): Down to 7% of peak

Collapse and Recover (L=300, slow growth): Down to 88% of peak

Smooth Transition (L=300, fast growth): Down to 90% of peak

Abundance (L=900, fast growth): Up to 280% of peak

The critical factors are:

L (carrying capacity): This determines whether renewable energy can match, exceed, or fall short of fossil fuel capacity. This is fundamentally about physics and engineering - energy return on investment, scalability, resource requirements, etc.

k₁_renew (growth rate): This determines how quickly we can build out renewable infrastructure. This is about economics, policy, manufacturing capacity, and political will.

k₂_renew (depreciation): This affects the final equilibrium level. Lower depreciation (longer-lasting infrastructure) means higher sustainable capital.

Model Limitations and Insights

This model makes several simplifying assumptions:

Independence: Fossil and renewable systems don’t interact. In reality, there might be competition for investment capital, labor, or materials. But this independence assumption keeps the model tractable and highlights the essential dynamics.

Smooth transitions: The logistic growth of renewables is smooth. Real buildout might be more erratic, with policy changes, technological breakthroughs, or resource constraints causing acceleration or delays.

No feedback: Collapsing fossil capital doesn’t affect renewable growth. In reality, economic disruption might slow renewable deployment - or accelerate it if it drives innovation.

Despite these limitations, the model captures something essential: the energy transition is a race between fossil fuel depletion and renewable energy deployment.

The “collapse” we experience depends on:

How much capacity renewables can ultimately provide (L)

How fast we can build them (k₁_renew)

When we start in earnest (C_renew_0 and initial growth phase)

Conclusion: Not Doomed, But Challenged

The separated SCLV model suggests we’re not necessarily doomed, but we face significant challenges. The model shows that:

Even in pessimistic scenarios, renewables provide a floor - we don’t collapse to zero like fossil capital does.

The transition can be smooth with fast deployment - Scenario 3 shows only a 10% dip with aggressive buildout.

Abundance is physically possible - Scenario 4 demonstrates that high L can lead to a richer post-transition world.

The key insight is that we have agency in this transition. The parameters k₁_renew and L are not fixed by fate - they depend on our choices:

Investment in renewable energy (affects k₁_renew)

Technological innovation (can increase L)

Infrastructure durability (lowers k₂_renew)

Efficiency improvements (increases effective L)

Starting early (larger C_renew before fossil peak)

We face difficult times - the model is clear about that. The fossil fuel decline is based on physics. But the depth and duration of the transition crisis depends on choices we’re making right now. The question isn’t whether we’ll face disruption, but how much - and what we’ll build on the other side.

Methods

The equations were solved using Python. The plots were prepared by Claude AI.

There is a bit of clickbait and channeling here. Also, I am no fan of systems modeling because it restricts the number of interactive variables - in order to make it simple enough to model! This is beyond ironic and delves into the realm of disingenousness. So, three points.

1) "What if Predicting Collapse Hastens Collapse" is the title and I was immediately intrigued, as this is something I have pondered ever since I became a "doomer" fifty-five years ago. (In 1969, I started looking to get out of the city "before the shit hits the fan.") But this is clickbait because Ugo is not looking at it from the angle of multitudes of people making collapse happen because they are preparing for it. Nor does he approach it from the idea of collapse being preferable. (Think of how the localized violence may actually be less oppressive than the system violence we all live under now. This is just one possibility. There are many others.) The article is not really about this aspect of individual and group actors affecting the social and economic systems. (Either for positive or negative results.) It is about Ugo's modeling of Mind-Sized System Dynamics Models. This is a worthy endeavor, but it is not what I thought he was going to talk about in this post.

2) The channeling effect. The title of the article is the "hook," to use an old journalism term, and the use of myth is another hook. But then Ugo straitjackets the concepts into cornucopians vs. doomers and gives a false definition of doomers. (He also equates doomers with catastrophists, which is another problem.) Here is his paragraph:

"The current debate sees two camps facing each other: the catastrophists and the cornucopians. The first group sees our civilization brought down by a combination of pollution, resource depletion, or overpopulation. The second sees technological progress breaking through all physical barriers and leading humankind to keep growing in power and numbers."

"Channeling" is an old term from the 1960s underground newspapers in the US that I used to sell (and read!) back in the late 1960's and early 1970s. It was an early version of the Hollywood term "spin" and means about the same. The way it works is to first restrict a term and secondly to box it in by definition. The effect is to follow 1 & 2 to the logical conclusion 3, which is what you intended to "prove" in the first place. In other words, you have a desired effect 3, which you pre-ordain by 1 & 2. As an aside, Karl Marx was real good at this, which is probably why the quasi-Marxist/Leninist writers in the underground newspapers were so aware of it. By the way, this is also why I have dismissed Marx as irrelevant since 1968. It was also a favored technique of the Tea Party from 2010 to 2016, when they were able to take over the Republican Party in the US. (The libertarian types got all their good ideas from us "lefties." I first noticed this in 1973.) But I digress.

Doomers are not necessarily catastrophists. There is a wide spectrum of doomers. The word itself comes from the Old Norse "dómr." It simply means judgment or sentence, but also has other extensions, for instance the court that passed judgment. In modern English usage it simply means, "We are judged and sentenced to pay the price." And of course, the court that has judged us is the ecosystem as a whole. We can certainly make an attempt to slip the sentence, like getting out of the city and living a rural life growing our own food. But this is not a solution in the conventional sense of trying to "fix the system." It presupposes that it will take time for the effects of fouling our own nest and giving the billionaires even more money to play out over a gigantic complex ecosystem. You are not going to wake up some morning and find out that the world has gone to shit before breakfast. It is not catastrophism. It will be a decline - sometimes steady, sometimes punctuated. As an aside, back in grad school, one of my teachers mentioned that the proper term for Stephen Jay Gould's "punctuated equilibrium" should actually be punctuated gradualism. The term applies here too.

So I am proud of being a doomer because it means I can see the problem clearly. It does NOT mean I am a greedy, grasping, gerontocratic gray-hair spending the millenials' future on trips to the Barbados in the dead of winter. Quite the opposite. I have been working on alternatives to the evil US and Western system since 1970. As I say so often, "If YOU would have listened to US fifty-five years ago, WE wouldn't be in trouble NOW."

3) The Mind-Sized System Dynamics Model. Ugo says, "This post presents a simple extension of the Single-Cycle Lotka-Volterra (SCLV) model that treats fossil and renewable energy systems as two independent capital stocks. The model was created in view of a “mind sized” approach proposed by Seymour Papert in 1980. To maintain the model simple, the two stocks (fossil-generated capital and renewable-generated capital) were treated as independent from each other. This is, obviously, an approximation."

In this SCLV model, the technique of applying first-order, nonlinear differential equations is applied to energy rather than predators and prey. In other words, what is important is the interaction between two variables. Not three, not four, not the large number of variables that exists in reality. The limit of modeling itself is that one must restrict the variables in order to make it workable. Even if one has access to supercomputers and multivariate statistics.

In a nutshell, this is the problem with modeling. One has to restrict the variables in order to make the model work. Here is a little blurb on the Lotka–Volterra model from Science Direct:

"The Lotka-Volterra model is defined as a mathematical representation of the dynamics between two interacting species, typically a predator and its prey, where population changes are expressed through a set of first-order, nonlinear differential equations."

I have been criticizing the use of modeling for decades, not only for its poor use of statistical methods, but because it takes up so much of the energy and financing that could instead be used for doing REAL projects. Like sustainable agriculture and landrace development - two of my fields.

Here is a real example of what I am getting at. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was developed by R.A. Fisher to make sense of the reams of agricultural data at the Rothamsted Experimental Station in the 1920s. AND you can still test your hypothesis by analysis of variance using a pencil and paper. You do not need computers, unlike principle components analysis (PCA). What we need now are simple solutions that actually work. We have one sterling example from 1970: Reduce, Reuse and Recycle. You do NOT have to spend a whole lot of time funding people who develop extensive computer models and furthering inequality between the blue-collar workers and the "professionals." Instead, you could just STOP wasting so much time, energy and money on bullshit that does not make our life better. This is what YOU the individual can do. And when collapse does actually accelerate and your life is rapidly sliding into a quasi-medieval lifestyle, you will be better off. I have been doing this for fifty-five years. It has greatly extended my lifespan (based on my family history and genetic load) and given me a life worth living.

The infamous bottom line. Our political and economic overlords are not going to allow you to make any REAL changes in the System and they have the guns and the police on their side. The System will collapse because it is unsustainable. Get out of the way and save yourself, your family, and as many of your local community as you can. If you can build local alternatives along the way, so much the better. There are plenty of us still doing this.

Here's what I've learned paddling Class V whitewater in my kayak. You go where you look. The surest way to end up in a huge hydraulic reversal (we call them 'holes') is to focus your gaze on that. You'll go right into it.

We seem to have an entire elite class with brainworms, who long for collapse because they are bored, or otherwise have no meaning in their lives. We could instead focus those intellectual resources on refinement of renewables/nukes -- but instead we spend incredible energy screaming about a collapsing world.

We will go where we paddle. And where we look.