We know very little about what the rich actually think, surely nothing like what transpires from their public declarations. I’ve always been thinking that the rich and the powerful are not smarter than the average commoner, such as you and I. But just the fact that they are average means that the smart ones among them must understand what’s going on. And what are they going to do about the chaos to come? They have much more power than us, and whatever they decide to do will affect us all.

Douglas Rushkoff gives us several interesting hints of what the rich have in mind in his book “Survival of the Richest” (2022)

The portrait of the average rich person from the book is not flattening. We are told of a bunch of ruthless people, unable to care for others (that is, lacking empathy), and convinced that the way to solve problems is to accumulate money and keep growing as if there are no limits. But Rushkoff tells us that at least some of them understand that we are going to crash against some kind of wall in the near future. And they are preparing for that.

Even without Rushkoff’s book, it seems clear to me that plenty of planning and scheming is going on behind closed doors. Large sections of our society are by now completely opaque to inquiry, and commoners have no possibility to affect what’s being decided. We know less of what’s going on in Washington’s inner circles than the Danish peasants knew of what was going on inside the Castle of Elsinore at the time of Prince Hamlet.

Of course, it is unlikely that the rich and the powerful will act as a single entity; they are a mixed bunch of individualists who do not normally collaborate with each other. Most of them seem to be mainly planning to create havens for themselves in some Northern regions that they may suppose won’t be too heavily affected by climate change. But it is also possible that a coalition of them could form to pursue some large-scale goals, from the extermination of most of humankind to radical planetary engineering.

The only thing we can be sure of is that they won’t tell us what they have in mind and that they will react aggressively if someone were to diffuse their plans to the public. So, you won’t find in Rushkoff’s book hints of truly dark plans in progress; at most, you’ll hear of rich people buying bunkers and stocking them with food, weapons, and ammo.

It is nothing new; it already happened long ago, at the time of the collapse of the Roman Empire. We have a document from the last decades of the Empire, the "De Reditu Suo" (of his return), in which a Roman patrician, Rutilius Namatianus, tells us of his travel along the Italian coast among abandoned cities, wastelands, ruined roads, and more. Namatianus was doing what a rich man of his time could do: he was running away from the ongoing catastrophe, trying to find refuge in a remote area where he thought he could be safer.

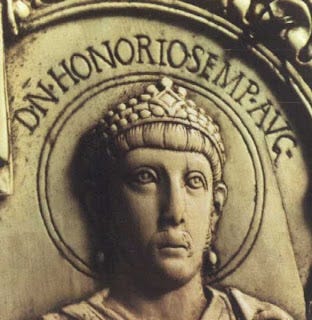

Namatianus had been the “praefectus urbi,” the emperor's delegate in Rome, and his job was, in theory, to defend the Roman citizens. Instead, he ran away with his possessions, probably taking with him money, provisions, and troops. He was doing nothing worse than other rich and powerful Romans were. Emperor Honorius himself had run away from Rome, settling in Ravenna, protected by the marshes surrounding the city and with ships ready to take him to safety in Byzantium if things were to get really bad. The chroniclers of the time tell us that he was more interested in his chicken than in the fate of Rome, and probably that’s not far from the truth.

We see a pattern here: when the rich Romans saw that things were going really out of control, they scrambled to save themselves while, at the same time, denying that things were as bad as they looked. We see that clearly in Namatianus' poem. Maybe Namatianus understood what was happening but refused to admit it to others. Or, perhaps more likely, he refused to admit it to himself. In any case, he never hints that Rome was doomed. At most, he says, it was a temporary setback, and soon Rome will be great again. Understanding something is most difficult when one’s survival is based on not understanding it.

The same pattern is unfolding today. We see subjects such as global warming being slowly, but surely, marginalized and eliminated from the news. If a problem can’t be solved, at least by conventional means, the best strategy is to ignore it, at least in public. Then, if something drastic is being planned to solve it, we’ll see that only when the plan starts unfolding. The only thing we can be sure about is that the plan's goal is to ensure the survival of the planners.

__________________________________________________________

Below, a post that I published a few years ago on “Chimeras” on the story of Rutilius Namatianus. (slightly revised).

Of his return: a Roman patrician tells of how he lived the collapse of the empire.

The 5th century saw the last gasps of the Western Roman Empire. Of those troubled times, we have only a few documents and images. Above, you can see one of the few surviving portraits of someone who lived in those times: Emperor Honorius, ruler of what was left of the Western Roman Empire from 395 to 423. He seems to be surprised, as if startled at seeing the disasters taking place during his reign.

At some moment during the first decades of the 5th century C.E., probably in 416, Rutilius Namatianus, a Roman patrician, left Rome to take refuge in his possessions in Southern France. He left to us a report of his travel titled "De Reditu suo", meaning "of his return," that we can still read today, almost complete.

Fifteen centuries after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, we have in this document a precious source of information about a world that was ceasing to exist, and that left so little to us. It is a report that can only make us wonder how could it be that Namatianus got everything so badly wrong about what was happening to him and to the Roman Empire. And that tells us a lot about how it is that our elites understand so little about what's happening to us.

To understand the "De Reditu" we need to understand the times when it was written. Most likely, Namatianus came of age in Rome during the last decades of the 4th century, during the reign of Theodosius 1st (347-395 C.E.) the last Emperor to rule both the Western and the Eastern halves of the Empire. When Theodosius died in 395 C.E., the Western Roman Empire went into its last convulsions, before its formal demise in 476 A.D. But, at the times of Namatianus, there still were Roman Emperors, there still was a Roman Senate, there still was the city of Rome, perhaps still the largest town in Western Europe. And there still were Roman armies charged to defend the Empire against invaders. All that was to disappear fast, much faster than anyone could have guessed at that time.

Namatianus must have been already an important patrician in Rome when Stilicho led what Gibbon calls "the last army of the Republic" to stop the Goths coming down toward Rome in a battle that took place in 406 C.E. Then there was the downfall of Stilicho, executed for treason on orders of Emperor Honorius. Then, there came the invasion of the Goths under Alaric 1st and their taking of Rome in 410 C.E. In total, Namatianus saw the fall of seven pretenders to the Western throne, several major battles, the sack of Rome, and much more.

Those troubled times also saw several figures we still remember today. Of those who were contemporary to Namatianus, we have Galla Placidia, the last (and only) Empress of the Western Roman Empire; it is likely that Namatianus knew her personally as a young princess. Namatianus must also have known, at least by fame, Hypatia, the pagan philosopher murdered by Christians in Egypt in 415 CE. He also probably knew of Augustine (354-430), bishop of the Roman city of Hippo Regius, in Africa. More historical figures were contemporaries of Namatianus, although it is unlikely that he ever heard of them. One was a young warrior roaming the Eastern plains of Europe, whose name was Attila. Another (perhaps) was a warlord of the region called Britannia, whom we remember as "Arthur." Finally, Namatianus probably never heard of a young Roman patrician born in Roman Britannia, someone named "Patricious" (later known as "Patrick"), who would travel to the faraway island called "Hibernia" (today known as Ireland) some twenty years after that Namatianus started his journey to Gallia.

But who was Namatianus, himself? Most of what we know about him comes from his own book, De Reditu, but that's enough for us to put together something about him and his career. So, we know that he came from a wealthy and powerful family based in Gallia, modern France. He attained prestigious posts in Rome: first, he was "magister officiorum;" something like secretary of state, and then "praefectus urbi," the governor of Rome.

During those troubled times, the Emperors had left Rome for a safer refuge in the city of Ravenna on the Eastern Italian coast. So, for some time, Namatianus must have been the most powerful person in town. He was probably charged with defending Rome from the invading Goths, but he failed to prevent them from taking the city and sacking it in 410. Maybe he also tried - unsuccessfully - to prevent the kidnapping by the Goths of the daughter of Emperor Theodosius 1st, Galla Placidia, who later became empress. He must also have been involved in some way in the dramatic events that saw the Roman Senate accusing Stilicho's widow, Serena, of treason and having her executed by strangling (these were eventful years, indeed).

We don't know if any or all of these events can be seen as related to Namatianus' decision to leave Rome (perhaps even to run away from Rome). Perhaps there were other reasons; perhaps he simply gave up on the idea of staying in a half-destroyed and dangerous city. But, for what we are concerned with, here, we can say that if there was one person who could have a clear view of the situation of the Empire, that person was Namatianus. As prefect of Rome, he must have had reports coming to him from all the regions still held by the Empire. He must have known of the movements of the Barbarian armies, of the turmoil in the Roman territories, of the revolts, of the bandits, of the usurpers, and the emperor's plotting. In addition, he was a man of culture, enough that, later on, he could write a long poem, his "De Reditu." Surely, he knew Roman history well, as he must have been acquainted with the works of the Roman historians Tacitus, Livy, Sallust, and others.

But could Namatianus understand that the Western Roman Empire was collapsing? Surely, he knew that there was something wrong with the empire, as is clear from his report. Just read this excerpt from "De Reditu":

"I have chosen the sea, since roads by land, if on the level, are flooded by rivers; if on higher ground, are beset with rocks. Since Tuscany and since the Aurelian highway, after suffering the outrages of Goths with fire or sword, can no longer control forest with homestead or river with bridge, it is better to entrust my sails to the wayward."

Can you believe that? If there was a thing that the Romans had always been proud of, that was their roads. These roads had a military purpose, of course, but everybody could use them. A Roman Empire without roads is not the Roman Empire, it is something else altogether. Think of Los Angeles without highways. Namatianus also tells us of silted harbors, deserted cities, a landscape of ruins that he sees as he moves north along the Italian coast.

But, if Namatianus sees what's going on, he cannot understand why (or he refuses to understand it). He can only interpret it as a temporary setback. Rome has seen hard times before, he seems to think, but the Romans always triumphed over their enemies. It has always been like this, and it will always be like this; Rome will become powerful and rich again. Namatianus is never direct in his accusations, but it is clear that he sees the situation as the result of the Romans having lost their ancient virtues. According to him, it is all the fault of those Christians, that pernicious sect. It will be enough to return to the old ways and the old Gods, and everything will be fine again.

That's even more chilling than the report on the decaying cities and fortifications. How could Namatianus be so short-sighted? How can it be that he doesn't see that there is much more to the fall of Rome than the loss of the patriarchal virtues of the ancient? And, yet, it is not just a problem with Namatianus. The Romans never really understood what was happening to their Empire, except in terms of military setbacks that they always saw as temporary. They always seemed to think that these setbacks could be redressed by increasing the size of the army and building more fortifications. And they got caught in a deadly spiral in which the more resources they spent on armies and fortifications, the poorer the Empire became. And the poorer the Empire became, the more difficult it was to keep it together. Eventually, by the mid-5th century, there were still people in Ravenna who pretended to be "Roman Emperors", but nobody was paying attention to them any longer.

So, Namatianus provides us with a precious glimpse of what it is like living a collapse "from the inside"” Most people don't see it happening - it is like being a fish: you don't see the water. And if you are a fish, you’d better keep thinking that water is forever. And, then, think of our times. You see the problem?

The "De Reditu" arrived to us incomplete, and we don't know what was the conclusion of Namatianus' sea journey. Surely, he must have arrived somewhere because he could complete his report. Most likely, he did reach his estates in Gallia, and, perhaps, he lived there to old age. But we may also imagine a more difficult destiny for him if we refer to a contemporary document, the "Eucharisticos" written by Paulinus of Pella, another wealthy Roman patrician. Paulinus fought hard to maintain his large estates in France despite barbarian invasions and societal collapse, but he found that land titles are of little value if no government can enforce them. In old age, he was forced to retire in a small estate in Marseilles, reporting that, at least, he was happy to have survived. Perhaps something similar happened to Namatianus. Even those who refuse to understand collapse are condemned to live it.

A most excellent piece. I agree with you that the rich and powerful are in general no smarter than the average "commoner." They have obviously been more successful at amassing wealth (usually = power), but I see three basic reasons for that.

Many simply "chose their ancestors well," inheriting their wealth. This says nothing about their intelligence or competence.

Some (many/most?) simply have fewer scruples than the rest of us. This is not related to intelligence or competence either, unless one considers that a willingness to violate society's norms is some perverted form of that. There are certain things most of us will not do even for vast sums.

Finally we must acknowledge that there are those who have truly earned their wealth by virtue of an extraordinary accomplishment, invention, or product. Even then, all we can say about them is that they are good at that one thing, or are good at turning it into wealth. But they are just as likely as the rest of us to be mediocre at other things.

You commented that when the rich Romans saw that things were going really out of control, they scrambled to save themselves while, at the same time, denying that things were as bad as they looked.

Perhaps this is not denial, but mere acceptance of the fact that even if one is rich and powerful, there are still limits to his ability to control the world around him. But to regain such control as might preserve him, he must cut himself off from almost everything, and what kind of life would that be?

Hello Ugo and commentators... somewhat related to this post, and the latest Oxfam report on how (the Big B) billionaires got richer during the pandemic while (the very small b) billions who suffer poverty every day lost ground to rising prices for basics... If I understand current economics correctly, about 100 families own about as much wealth as all the families in the poorer half of the entire world. And those few hundred individuals are getting a bit nervous about the rest of us .

IDK if Ugo's series on exterminations is on Substack.com or Blogger.com but it's time to find it and reread it ... ArtDeco