Venezuela: The Plan Behind the Attack.

When you want to sell something, you don't just need to have a product; you also need to create a market.

Though this be madness, there is method in't — Shakespeare, Hamlet

The dust is slowly settling after the Venezuelan operation, and I think we can assess what has been done and why. For one thing, at least, it is refreshing that they stopped selling us the idea that they were attacking other countries for their own good. Most commenters and the US administration plainly stated that it was done for oil. But what was the logic of using military force? After all, you don’t normally kill or abduct the service station attendant when you need gas for your car.

I think there is a plan. Maybe you can call it an evil plan, but it is more clever and structured than most people would imagine. It all rotates around a simple equation: profits are the difference between revenues and costs, also defined in terms of “return on investment” (ROI). Nobody will invest money in something that has a negative ROI.

In the case of oil, there is a parameter that governs the ROI. It is called EROI (energy returned for energy expended). Oil is produced to generate energy, but to produce oil (extracting, transporting, refining, distributing, etc.) you have to use energy. EROI is the ratio of the energy produced to the energy expended for producing it. An EROI smaller than one means you lose energy in the process.

The concept of EROI is often illustrated in terms of a lion chasing a gazelle. If the lion spends more energy running after the gazelle than it gains by eating it (EROI smaller than one), then it will starve to death.

The ROI is not exactly proportional to EROI because, in business, there are plenty of plumes of smoke and mirrors that may lure investors in by promises of fools’ gold (more correctly in this case, snake oil). But, in the end, you cannot make a profit for long from something that you produce at a net loss. Low EROI means low profits.

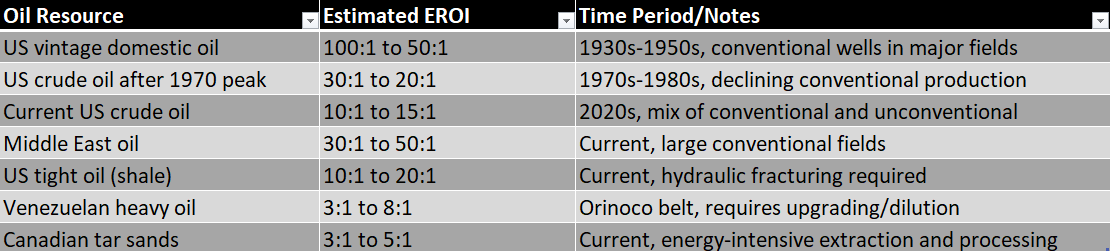

Let me show you an EROI table for hydrocarbon products to guide us to understand the story. EROI calculations are complex, and these values are just estimates compiled by me from various sources. I think they are qualitatively correct, but no more than that. Note also that the values are calculated at “the well’s mouth,” but for tar sands and heavy oil are after upgrading to synthetic crude oil.

In the past, the high EROI of oil and other fossil hydrocarbons led to rapid economic growth. You may have heard that oil extracted in the US in the 1930s had an EROI of 100:1. It is an exaggeration, but not far from the truth. At a time when it was enough to hammer a steel tube into the ground to get oil, these values were possible. On average, the “light crude” that flowed out of US wells up to the 1950s could have an EROI in the range 50:1. It was an excellent yield. It created the American World Empire.

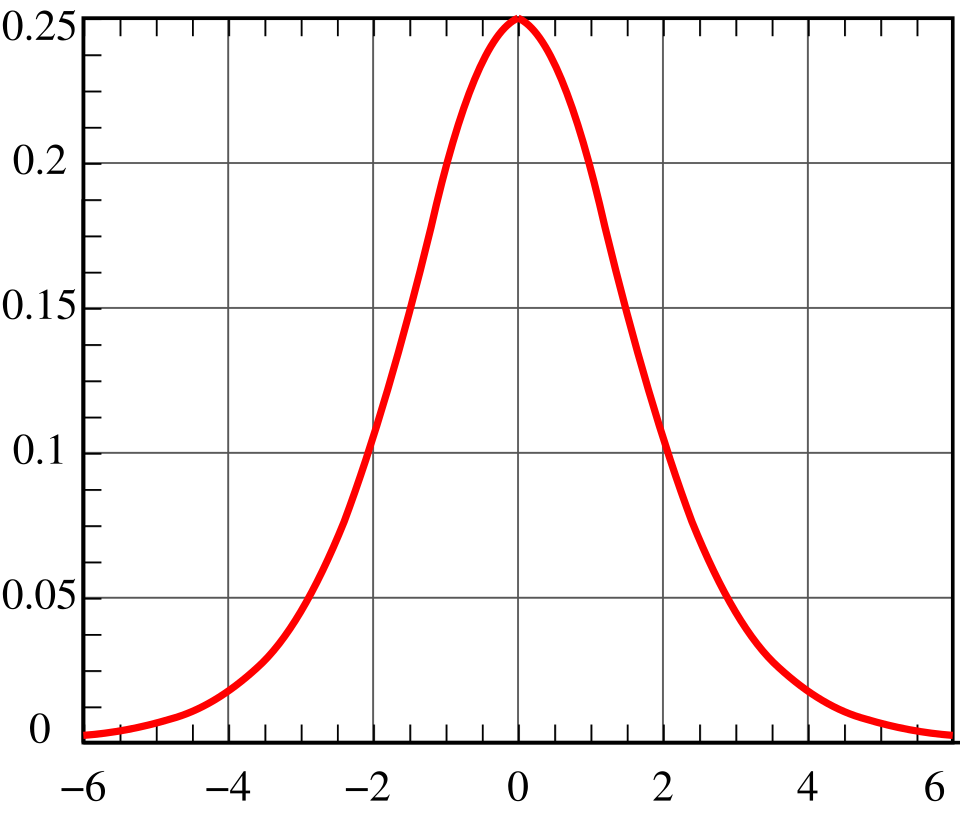

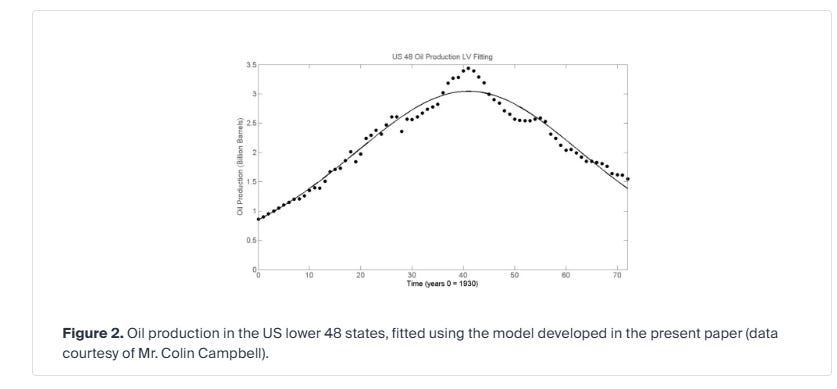

Now, the crucial point is that EROI is not constant. It varies with time. People tend to exploit first the resources that provide the largest return, that is, those that are not deep, flow easily, and are not far away. But these resources are not infinite, and gradually the industry has to move to lower EROI resources; deeper, dirtier, and farther. Lower profits mean lower investments. If the oil industry were operating in a free market, then optimizing yields leads to the well-known, bell-shaped Hubbert production curve. (We showed that here).

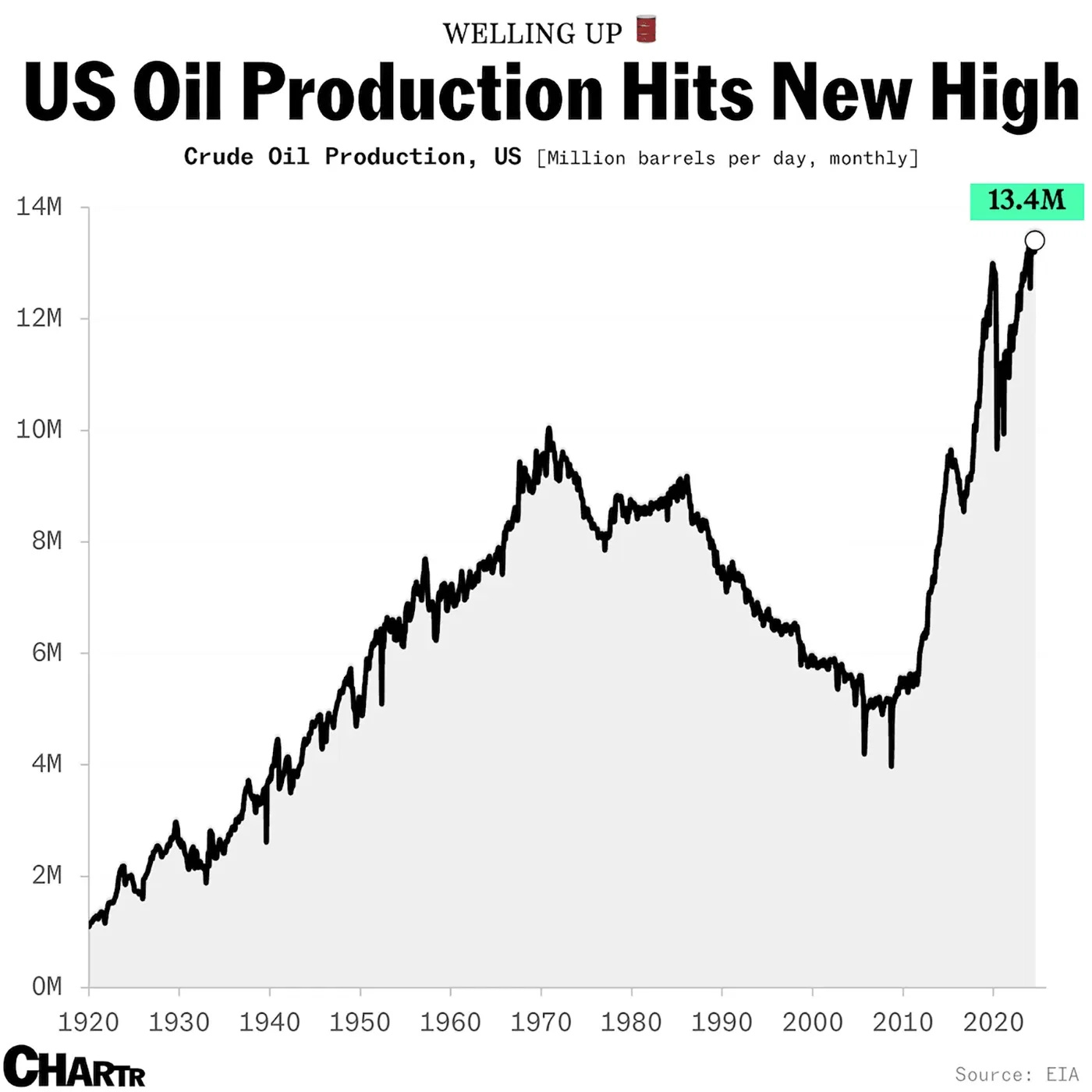

It happened with the US oil production. When the curve started going down, the EROI of the domestic US oil was probably around 20-30. That was low enough to cause profits to dwindle. Companies reduced their investments, and the result was a decline in production. (source)

But, of course, people don’t stay still when they see their profits plummeting. They try new things, develop new technologies, and change the rules of the game. And that’s what the US oil industry did. For some time, they compensated with imports mainly from the Middle East, where the oil EROI was still good (probably around 40). Then, with the 21st century, they dropped the Trump Card (not the Donald, yet), and moved to exploit a new resource: shale oil (or “tight oil”) in the US.

Shale oil production is reported to have a decent EROI, probably around 20-30, (although some estimates say it is much less). It required completely new technologies and huge investments, but the industry could find the necessary resources at a time when oil prices were kept high by a strong demand. By the 2010s, the oil production trend in the US changed its slope, following a new bell-shaped curve. With this resource, the US was propelled back to its earlier role of top dog in the world’s pack.

There exists a huge amount of shale oil reserves in the US, but even for shale oil the harsh law of the EROI holds. The average EROI is declining, and shale oil production may have already started its decline.

This is our predicament: as long as we depend on fossil hydrocarbons, our civilization will collapse if the EROI of energy production goes below one. Actually, it will collapse even for larger values. Charles Hall and his coworkers estimate that the actual minimum EROI to keep civilization alive is 3:1, but that would be a condition of mere survival in conditions of stark poverty; think of something like Germany in 1944.

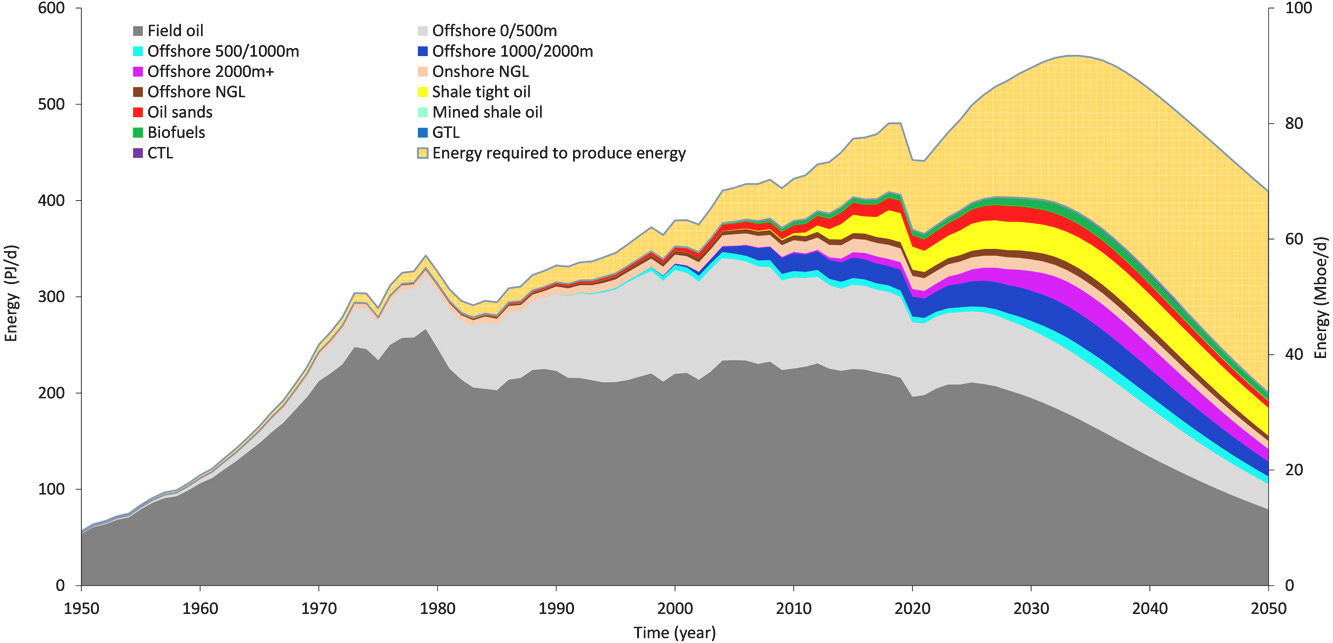

The image below is from Delannoy et al. (2021). Note the continuous increase in the dark yellow area of the curve. It is the “energy needed to produce energy,” the denominator of the EROI ratio. Around 2045-2050 the average global EROI of liquid fuels will be around one. Game over.

But when the Titanic sank, not everyone sank at the same time. So, the Western oil industry may think about repeating the trick played in the 2000s with shale oil, using a new Trump card (this time, the Donald). That is, investing in a new oil source that can keep the Titanic afloat for a while, even though the passengers in the lower decks will drown.

It boils down to two possibilities: the Canadian Tar Sands and the Venezuelan Heavy oil. Both are theoretically large resources, but both have a huge problem: they have a low EROI. They are expensive to extract, to clean, to refine, and to be turned into liquids. We are discussing EROI values well under 10:1, probably under 5:1. Consider also that the produced fuel has to be used in inefficient thermal engines. When the energy produced by Venezuelan oil arrives at the wheels of your car, you are lucky if you have an EROI larger than one. Canadian tar sands are probably even worse.

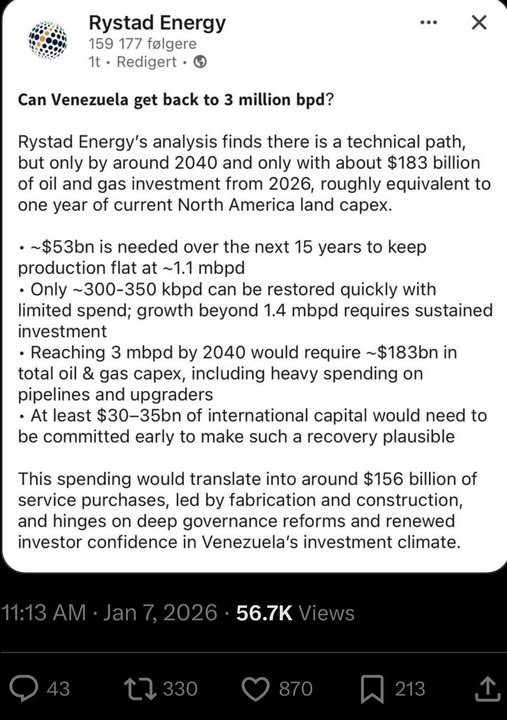

That’s the reason why, right now, Venezuela produces only about one million barrels/day, around 1% of the total world production of combustible liquids. To make the Venezuelan industry able to produce substantially more would require investing billions of dollars over a span of at least a decade. Rystadt Energy estimates it would take no less than 16 years and at least $183 billion to produce 3 million barrels of oil a day, just one third of what the US or Saudi Arabia produce today. The uncertainties involved are enormous, including the likely possibility that, by then, the internal combustion engine will be a museum piece.

It is true that nobody sane in their mind would plunk good money into such a difficult and uncertain enterprise:

But things are more complicated than that. The “free market” is an interesting concept, but not more real than phlogiston and cosmic ether. In the real world, there holds the WYCWYC principle (grab what you can, when you can). Perhaps the most interesting resource to be grabbed is government money. No one ever estimated the EROI of corrupting politicians, but it is probably very high. So, if the government pays, then oil companies will be more than happy to upgrade the Venezuelan heavy oil production. That would be a very bad deal for taxpayers, but you know who wins in these kinds of confrontations.

Actually, the plan is more subtle than this. You see, the idea to throw good money at bad oil just won’t work. It would be suicidal for the oil industry because it is tantamount to beggaring their own customers, the Western citizens (actually, European taxpayers will be beggared first, but that’s a detail). Already now, as a private customer, you would probably be unable to afford fuel produced from Venezuela’s oil reserves, even though they’ll sell you the idea as if they were doing you a favor. If they really spend so much of your money to control Venezuela and upgrade its production facilities, then the only thing on wheels you will be able to afford is likely to be a bicycle (if you are lucky).

So, the plan involves not just creating a product, but also a market: a military market. The military doesn’t care how much they spend on their hardware; you, the taxpayer, foot the bill. So, that’s the new market of oil products: not anymore your old Toyota pick-up, but larger and more expensive toys for the military, tanks, planes, missiles, etc.

That explains why Trump plans to expand the US military budget from about 1 trillion dollars/year to one and a half trillion. That extra half trillion is more than enough to finance the control and the exploitation of the Venezuelan oil, and the Canadian tar sands as well. And it also creates the market for it in the form of military hardware.

Clever, right? Though this be madness, there is method in it. By implementing the plan, our leaders gain power and riches; we, ordinary people, lose everything. But that’s the way the world works, and if you didn’t realize that yet, I can only suggest that you stop watching the news on TV.

Yet, it is also true that the best plans of mice and men often gang agley. It is not obvious that the US can really take over Venezuela without facing serious resistance. The plan also involves silencing the climate science community and convincing the public that global warming was nothing more than a scam engineered by a group of evil scientists. That’s being done using a combination of propaganda and defunding, it seems to be working, right now. But it may also encounter strong resistance as the warming damage becomes more and more evident. Finally, with such a low EROI and high costs, the huge financial effort could crack the US economy. The very survival of the US as a state would be at stake.

Even if the plan works, it might backfire in the medium term. The effort on crude oil and the military buildup would leave the US in a situation of technological backwardness in comparison to East Asia, and China in particular, which is rapidly moving toward a renewable-based economy and a high-tech, light, and effective military apparatus.

Think in terms of Trabant vs. Tesla. In a commercial war between petro-states and electro-states, I am afraid that Trabant cars wouldn’t have much of a chance against Teslas. Even if things go kinetic, in a major war, heavy tanks won’t have better chances against nimble drones than horses had against tanks during WWII.

Wind and PV renewables today have an EROI some 5-10 times larger than that of Venezuelan crude oil. We can get free from our dependency on oil and avoid being enslaved by the powers that be if we move in the right direction. Unless you are a member of the petro-elite, you’d better cheer for renewables and electrification. It is our only chance of survival.

Le riserve venezuelane (240 miliardi barili) hanno EROEI attuale 3:1, economicamente marginale. Tecnologie catalitiche documentate (THAI/CAPRI) potrebbero portarlo a 5:1 - la soglia critica per sostenibilità industriale. A quel punto, il Venezuela diventerebbe strategicamente equivalente all'Arabia Saudita per gli USA: controllabile geograficamente, capace di compensare il declino dello shale americano (picco ~2030) e prolungare l'egemonia energetica USA di 40-60 anni.

Il timing dell'escalation militare USA (2014-2025) coincide con la maturazione di queste tecnologie e l'inizio del plateau produttivo interno. Non si tratta solo di petrolio, ma del controllo dell'ultima grande riserva emisferica quando l'EROEI globale declina inesorabilmente.

Merci beaucoup pour vos analyses très intéressantes, c'est toujours un grand plaisir de profiter de vos lumières !