The End of Conspicuous Consumption: the Great Jump Into the Financial Singularity

As a comment to the previous post by Ian Schindler on the “Financial Singularity” I am reposting an earlier post (slightly edited) on a similar subject that appeared on the old version of the “Seneca Effect.” During the Covid epidemic, people found themselves locked inside their homes, unable to use the money they had. That may have been the harbinger or larger changes to come. Are we going to see the end of the historical phase of “conspicuous consumption”? It was a historical anomaly, and it can’t last long. It will cease to exist not when money will disappear, but when there will be nothing to buy with it. (image above created with Dezgo.com)

The Problem of the Shipwrecked Sailor: When Money Becomes Useless

The Covid crisis highlighted an already existing problem: that money is useless if you can't buy anything useful with it. It is the problem of the shipwrecked sailor on a deserted island. (image from Wikimedia): money won't help him survive. So, lockdowns and restrictions gave us a taste of a future where money may be worth nothing simply because there is nothing you can buy with it. It is a problem ultimately connected with the unavoidable depletion of the fossil fuels that form the basis of our economy: with less energy, we cannot keep making the stuff that makes it possible to indulge in conspicuous consumption. So, after the Covid, society will never be the same. Taking into account that history never repeats itself, but it does rhyme, here I examine the situation starting with a parallel with the history of the Roman Empire.

The Roman Crisis: When Money Couldn't Buy Anything

Imagine living in Rome during the 1st century AD (the time of Lucius Annaeus Seneca). Rome, with perhaps one million inhabitants, was the largest city in the world and probably the largest emporium ever seen in history. Through the Silk Road, one caravan after the other were bringing to Rome all sorts of goods from Asia: pepper, cardamom, cloves, cinnamon, sandalwood, pearls, rubies, diamonds, and emeralds. And then ivory, silk, glassware, perfumes, jewels, unguents, and much more: exotic birds, special food, slaves to be used as workers and sex toys. Then, there was the entertainment: in Rome, you had theaters, chariot races, gladiator games, fights among exotic animals, and all sorts of performers with their magic tricks, songs, and spectacles.

You could enjoy all that if you had money. And the Romans did: they minted money in abundance. They had control over the richest precious metal mines of the ancient world in the northern region of Hispania. There, tens of thousands of slaves, perhaps hundreds of thousands, were engaged in a work that Pliny the Elder described as "the ruin of the mountains" (ruina montium), the process of crushing rock into sand to extract the tiny specks of gold and silver it contained.

The Romans paid their legions with the gold and silver they mined. Then, the legions would invade regions outside the Empire and capture slaves that would mine more gold to pay more legions. And, as long as the mines were producing, the Romans had gold aplenty, even though a lot of it was sent to China and to other regions of Asia to pay for the luxury goods they imported. That kept the economic machine of the empire working. For an empire to exist, money is everything.

Of course, then as now, not everyone had the same amount of money. In Rome, the rich took most of it, but some money trickled down to the artisans, the performers, the employees; everyone from cooks to prostitutes would get a share, maybe a small one, but still something. Even the slaves, destitute by definition, could own a little money when their masters would give them a few coppers to buy a cup of Falerno wine or admission to the chariot races.

But the rich Romans were truly rich. And their lifestyle was all based on showing off their wealth. Read this excerpt from Cassius Dio about a wealthy Roman patrician, Vedius Pollio.

. . . he kept in reservoirs huge lampreys that had been trained to eat men, and he was accustomed to throw to them such of his slaves as he desired to put to death. Once, when he was entertaining Augustus, his cup-bearer broke a crystal goblet, and without regard for his guest, Pollio ordered the fellow to be thrown to the lampreys. Hereupon the slave fell on his knees before Augustus and supplicated him, and Augustus at first tried to persuade Pollio not to commit so monstrous a deed. Then, when Pollio paid no heed to him, the emperor said, 'Bring all the rest of the drinking vessels which are of like sort or any others of value that you possess, in order that I may use them,' and when they were brought, he ordered them to be broken. (Roman History (LIV.23))

This story must have been well known since is reported also by Seneca, Plinius, and Tertullianus. That makes me suspect that it is false or at least exaggerated. Apart from the "lampreys" that were probably "morays," it may well have been a fabrication by Octavianus, aka Augustus, who was truly an expert in self-promotion. But it doesn't matter whether the story is true or not. The ancient Romans found it believable, so it gives us a hint of their way of thinking.

Probably, the Romans didn't see the moral of the story in the same way we see it nowadays. For them, it was perfectly normal that slaves could be put to death by their owners at any moment for any reason. The point of this story is that it shows that the Romans were practicing what we call today "conspicuous consumption." Pollio was filthy rich, and he loved to show off his wealth. Surely, he was not the only one: there are other examples of rich Romans displaying their wealth with sumptuous villas, lavish entertainment, fashionable clothes, jewels, and entourages of slaves and hangers-on. Then, the Emperor was the richest person in Rome. It was traditional that he would show his wealth and power by distributing food to the poor and entertaining citizens with extravagant games and spectacles.

In short, Imperial Rome was not unlike our age: the rich were enormously rich, but something of their wealth trickled down to the rest of the people. On all the steps of the social ladder, people played the consumption game in order to keep up with the Joneses. It was always the same story. Money is a tool for commerce, of course, but also a way to establish the social hierarchy.

Then, things started going wrong, as they always do. The Roman Empire controlled a large territory that stretched from Britannia to Cappadocia and that required an enormous military apparatus that was becoming more expensive. We have no records of the output of the precious metal mines in Roman times, but from the archeological data, it is clear that depletion was already biting during the early centuries of the Empire. It is typical of mining: you don't run out of anything all of a sudden, but the cost of extraction keeps increasing.

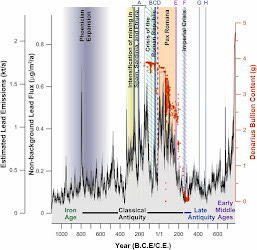

Surely, enormous efforts were made to try to stave off the decline of the mines. But the Seneca Cliff is unavoidable when you deal with non-renewable resources. The cliff started approximately at the beginning of the 2nd century AD. One century later, the imperial mines had ceased producing anything. They would never completely recover. (image from McDonnell et al.)

No gold, no empire. The mining collapse nearly brought the empire to an end during the 3rd century. It was a series of reciprocally reinforcing effects. The gold that was sent to China couldn't be replaced by mining. Then, less gold meant fewer troops, which meant fewer slaves, and that, in turn, meant even less gold. The result was a series of civil wars, foreign invasions, general turmoil, and overall economic decline.

The Roman Empire could have disappeared by the end of the 3rd century. In practice, it survived in a much poorer version for a couple of centuries. For one thing, the Romans couldn't afford anymore the luxuries that they once would pay with the gold they mined. As you would expect, the poor were the first to be hit, while the rich tended to maintain their extravagant lifestyle as long as they could. But the whole society was affected.

For the late Roman Empire, the problem was not just that the system had run out of gold. At some point, the Romans must have stopped, or at least greatly reduced, the flow of luxury goods from China. At that point, the rich Romans still had some gold. See this gold solidus coin minted at the time of emperor Constantine the Great, in mid 4th century AD.

But what could you buy with these beautiful coins? At that time, all the Western Roman Empire could produce were legions and tax collectors and, without imports from abroad, Rome had become a grim military outpost, not anymore the greatest emporium of the world.

Those who still had gold found themselves in the position of a shipwrecked sailor on a deserted island. Coconuts aplenty, perhaps, but no way to play the game of conspicuous consumption. Already with Augustus, the first emperor, we see a legal trend that aimed at limiting the excesses of wealth that the Romans could display. It was a gradual process completed only with the diffusion of Christianity in Europe and Islam in North Africa and the Middle East. It was unavoidable, and it happened.

So, in these late Roman times, gold had lost much of its luster. Those who still had it started burying it underground, with the idea of keeping it for better times. Modern archaeologists are still finding gold buried at that time. That was the probable origins of our legends about dragons living in caves and sitting on hoards of gold. People knew that plenty of gold had been buried, but, unfortunately, they lacked the metal detectors we have today! In any case, that was the end of the Roman Empire. As I said, no gold, no money, no empire.

Creative money: the relics of Middle Ages

When the Roman Empire faded, it was replaced in Europe by the era we call the Middle Ages. Then, people found themselves with a big problem: how to keep society together without the precious metals needed to mint money? And, even worse, without much that money could be spent on? The Middle Ages were a period of fragmented petty kingdoms and scattered villages, but there still was a need for a commercial system that would move goods around. But how to create it without metal money?

Our Medieval ancestors creatively solved the problem with a completely new kind of money. It was based on relics. Yes, the bones of holy men, meticulously collected, authenticated, and issued by the authority of the time, the Christian Church. Not only were relics rare and sought after, but they could also provide a service that not even the Roman gold could provide when it was abundant: health in the form of divine interventions. (In the figure, 18th-century relics owned by the author. They look like coins, they feel like coins, they are shaped like coins -- they are coins!)

These relics were a form of virtual money but, after all, all money is virtual. Even a gold coin promises something (wealth) that in itself cannot guarantee unless there is a market where you can spend it. And the fact that money can be spent depends on people believing it to be "real" money, mostly an act of faith. In the same way, a relic is a virtual object that has no value in itself. It promises something (health) that can be delivered if you believe in it. It was, again, an act of faith based on the belief that the little chunks of bone that the relics contained were actually coming from the body of a holy man of the past.

The beauty of the relic-based monetary system was that relics were not "spent" in markets. You could own relics, but you could grant their health benefits to others and still keep the relics. In other words, you could spend your money (eat your cake) and still have it!. Relic-money was managed mainly by public institutions such as monasteries and churches. They owned the most prized relics and were the places where pilgrims flocked to be healed by the powerful holy aura that these relics emanated.

The commercial system of the Middle Ages evolved in large part around relics. Travel was encouraged through pilgrimages to the holy sites, and that created an exchange economy based on charity. Conspicuous consumption was impossible in the relatively poor economy of the Middle Ages. Consequently, the Christian philosophy de-emphasized consumption and condemned social inequality. The highest virtue for a Medieval person was to get rid of all their material possessions and live an austere life of privation. Of course, that was more theoretical than practical, but some people were putting this idea into practice: just think of St. Francis.

The system worked perfectly until new precious metal mines in Eastern Europe started operating in late Middle Ages, bringing metal currency back to Europe. A new period of expansion followed that eventually led to our times of renewed conspicuous consumption. And that's where we are.

The Romans and us: the same problems.

We know that history never repeats itself, but it does rhyme. So, where do we stand now? Today, the money that keeps the Global Empire together is not based on precious metals; we don't risk collapsing because our mines cease producing gold. Indeed, there is clear evidence that gold production and economic growth decoupled worldwide in the 1950s. So using gold as the basis for a monetary system went out of fashion in the 1970s.

Our money is not linked to anything, nowadays. It floats free in space, a ghost of what once were heavy gold coins. But we still have it and our rich men are so filthy rich to put to shame the Roman ones (even though our multi-billionaries don't have the right to throw their servants into the pool of the morays, not yet, at least).

Apparently, we are more clever than the ancient. They didn't have paper, didn't have the printing press, they couldn't print paper money. And they couldn't even imagine what a cryptocurrency is. We can do much better than anything they could invent. So we will never face the same problems, right?

Not so simple. Yes, we do have paper money, cryptocurrencies, and the like. But don't think that the Romans didn't try to replace gold with something else. Even without paper, they could have used earthenware, papyrus, parchment, or whatever. But if they tried that, it didn't work. The problem is always that of the shipwrecked sailor. You may have money in one form or another, but if you can't buy anything with it, it is useless. Even if you have gold, there is not much you can buy in a collapsed economy.

And there we stand: we are all shipwrecked sailors and that has been shown most clearly by the Covid pandemic. Think about that: you were locked at home, you couldn't go to a restaurant, take a trip, get a drink, go to the beach, go dancing, nothing like that. Not that commerce disappeared: we could still buy anything we wanted from Amazon and have it delivered home. But, as I already noted, money is not just a tool to buy things. It is a tool to establish the social hierarchy by means of the game of conspicuous consumption. That's a game you can't play alone, at home, in front of a mirror. No more than a shipwrecked sailor, alone on his island, can gain a higher social status by eating more coconuts.

In the end, the pandemic simply brought to light something we should have known already: that we can't indulge in conspicuous consumption for much longer. Running out of gold is not a problem for us. The problem is that we are gradually running out of fossil fuels, and those fuels are what allowed us to consume so much and waste so much. The pandemic has given us a taste of the things to come.

So, can we think of a creative solution for the future that awaits our civilization as it runs out of the energy sources that power it? Maybe we can find inspiration from the Middle Ages. As I said, history never repeats itself, but we may be moving toward a historical phase that rhymes with the way the economy of the Middle Ages functioned. So, the Christian Church may be replaced by the entity we call "Science" (with a capital "S"), supposed to be able to dispense physical and spiritual health to its followers. And that may generate trade and movement of people and goods, as well as establish a new hierarchical order.

We may have already seen hints of this evolution. First, the Covid epidemic has heavily damaged the universal health care system of the countries that had it. With the fear of being infected and with hospitals being converted to Covid care centers, now good health care is not for everyone: it is a new form of conspicuous consumption for those who can afford it. The ancient pilgrimages to holy sites could be replaced by trips to the best hospitals and health care centers.

Then, would there be an equivalent of holy relics in the future? So far, nothing like that has emerged, but we may see the coming vaccination certificates as "tokens of virtue" that separate the "haves" (those who are vaccinated) from the "have nots." (those who don't want, or who can't afford, to be vaccinated). But that's hardly a functional hierarchy-creating system. Eventually, it could be replaced by a "point system" not unlike the shèhuì xìnyòng tǐxì, the social credit system being developed in China. By all definitions, that's a kind of monetary system that establishes a hierarchical system not based on conspicuous consumption. That may well be the future.

And, as always, history keeps rhyming.

The owners of those buried Roman hoards that occasionally turn up were probably overtaken by sudden, unexpected “life reversals” that prevented them going back for their stashes. Buried items are not locked up, hence they are only safe if NO ONE knows about them. Unfortunately, if an owner suffers an unexpected demise, he takes the secret location of his stash with him to the grave.

The fact that money is useless if there is nothing to buy eludes people even today. The belief in the law of “supply and demand” is so strong that most people think a sufficiently large sum of money can coax anything one wants out of hiding, or motivate an aspiring seller into producing it. Sometimes that is just not possible.

A good example can be found in Europe today. The EU wanted to buy artillery shells for Ukraine at $2K per round. They appropriated money for the purpose, but the necessary production capacity just doesn’t exist in the West, so all that was accomplished was that the existing shells rose in price to $8K per round.

Back in high school, our Russian professor used to tell us about his annual trips to visit relatives in the old Soviet Union in the 1960s. Back then during the Cold War, it was always described to us as a poverty-stricken place. But as he explained, the reality was that people had adequate money. There just wasn’t very much in the way of consumer goods for people to buy, because most of the factories were devoted to making other things. Whenever a few scarce consumer goods became available at the local store, people would line up for hours outside, hoping to get a chance to buy one of those few items. Most came away empty-handed, despite having the money.

A final thought: it is said that gold is not the basis for our monetary system, and in the sense that none of the world’s currencies are gold-backed, this is true. But then why are central banks all over the world still so anxious to own it?

Very interesting article, Ugo, with significant parallels with our current civilization. I think your view on the Middle Ages is not quite accurate, though.

Following the Roman Empire (after the Roman Republic), and its final demise, the Middle Ages extended over a thousand years in Europe. More time elapsed during the Middle Ages than since the Middle Ages ended, in 1453 according to most scholars or1492 as the latest date.

The concentration of power and relative wealth (wealth inequality) was never, ever diminished during this millenium. More than relics (I don't deny that relics were a major currency), land ownership was the real marker of wealth, power and prestige during the Middle Ages, and the source of energy were animal and (often forced) human labor. During the Middle Ages, the economic system changed several times, stabilizing around the feudal system, which also describes how the whole medieval society functioned from the 9th to the 15th century, or between the 10th and the 15th century (if we consider that the central state of the Carolingian Empire doesn't qualify even with other qualifiers of feudalism), or between the 10th and the early 18th century if we include a long transition period between feudalism and capitalism. This is a matter of definition. But in any case, in a much poorer economic environment, with less technology, less sophistication and less population, the Middle Ages and within, the feudal society, operated with even more extreme inequality than the Roman Empire. Inequality was actually the visible framework and outspoken ideology and justification of feudalism, without the (partial) pretense of the later capitalistic system. We are now transitioning back to a feudal system; it is not immediate as was not immediate its demises, but we can see the signs everywhere. Adam Flint, author of the prospective fiction, "Mona."