Christmas is celebrated in many different ways by Christians all over the world. One is the “nativity scene” or the “crèche” (“presepio” in Italian), a tradition still very much alive in Latin countries. It is a way to celebrate the end of Winter and the start of the new season with a bright display of hope. This tradition is said to have been created by St. Francis of Assisi during the 13th century, but I like to think that it may have started much earlier, perhaps with the Roman Empress Galla Placidia during the 5th century AD. (picture above: a presepio near Florence, Italy.)

Let me start by asking you a small feat of imagination. Close your eyes and imagine a scene of a long, long time ago, more than 15 centuries before our time. Imagine a young Roman princess. Imagine she has lived all her life inside beautiful palaces, wearing splendid dresses and expensive jewels, walking inside closed gardens rich in statuary and fountains. Always guarded, always protected, always secluded, as it is the usual lot of princesses.

And then imagine the same princess in a completely different situation. She is in the mountains at night, sitting at the front of a covered wagon in which she has been traveling a long road away from Rome, slowly pulled onward by a team of oxen. Around her, the winding column of wagons has been carrying the entire nation of the Visigoths. It is a cold winter night. The caravan has stopped, and the princess sits there, wrapped in a heavy woolen mantle, looking at the tall Barbarians and their women busy lighting campfires and preparing food. She listens to the distant murmur of their songs. They are Christians, but they are still singing prayers to the ancient Earth Goddess, Hertha, or other gods of fire and thunder. And maybe they still carry the wooden statues of their pagan gods in one of those wagons.

The princess’s name is Galla Placidia, the daughter of Emperor Theodosius, who was said to be “The Great.” Her title is Puella Nobilissima, “most noble girl.” In the whole Western Empire, there is only one person above her in rank: her brother, Honorius, the ruling emperor who lives in his secluded palace in Ravenna, the city no army ever managed to take except by ruse.

What is a Princess doing with those Barbarians? She was kidnapped. She was in Rome when the city fell to the Visigoths. Yes, Rome; the eternal city, the capital of the world, the seat of Emperors, the center of Christianity, the city that had never fallen to an invader for nearly a thousand years. And yet, the Visigoths, Barbarians, poor, uncouth, uncivilized, ignorant, and what you wanted to call them, had managed to break in and take the city. The shock all over the Empire had been immense. In the faraway city of Carthage, in Africa, a Christian Bishop named Augustine was so distressed by the news that he started writing a book titled De Civitate Dei, “The City of God,” inspired by these events. A book that people would still be reading many centuries afterward.

When the Visigoths left Rome after having sacked it, they were loaded with gold and silver. But perhaps the highest prize they were carrying was Galla Placidia herself — daughter and sister of Roman emperors. What could prove the might of the Gothic nation better than that? We may imagine that the Goths were amazed by her. We know that her mother, Galla, was said to be “the most beautiful woman in the whole Roman Empire,” and we may think that her daughter, Placidia, was no less handsome.

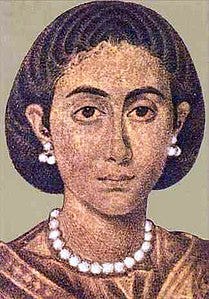

This picture gives us an idea of what a Roman noblewoman would look like during the last decades of the Empire. It shows Serena (ca. 360-408), cousin and foster mother of Galla Placidia. Note the two strings of pearls she wears: only the members of the Imperial family had this privilege. Galla Placidia would wear the same kind of double string of pearls as we see in the bas-relief below, the only image of her that we can consider reasonably realistic, although not as detailed as that of her cousin, Serena. The inscription says, “Domina Nostra, Galla Placidia, Pia, Felix, Augusta."

If the Visigoths were fascinated by Placidia, we may also imagine that Placidia was fascinated by them. Historians never mention that the Goths had to take Placidia away from her palace while screaming and dragging her feet. For her, 22 years old at that time, it was an adventure: a new world, new people, a new language, new uses, and new places to see. And we may imagine that on one of those cold nights, while she traveled with the Barbarians, Placidia would look at the stars as she had never seen them in a sky of clarity that today we can’t even imagine; the sky of a world that was shrinking to nearly nothing, its cities depopulated, its roads abandoned, its farmland left to transform into a forest. Around Placidia, there was no human light except the campfires of the caravan so that she could see that fantastic sky. The sky that has fascinated humans for millennia, and that Vincent Van Gogh represented in an eerie and haunting painting. The sky that would still fascinate us if we could see it as Placidia did, had we not dirtied it with our waste.

Of course, this is just imagination. We cannot know what a Roman woman who lived 15 centuries ago could have had in her mind. And yet, imagination is one of the things that make us human, and the image of a Roman princess looking at the clear night sky while traveling with the Barbarians gives us a link that no treatise in history can provide. It is a bond between us and a person who lived in a world so similar to ours in so many ways. An Empire that was collapsing, a civilization that was shrinking, a treasure of art and knowledge that was going to be dispersed. And a princess who may have been perfectly aware of that and who may have been thinking of what she could do to avoid the worst.

We know what Placidia did. While the job of Roman nobles, up to then, had been to fight the Barbarians, she decided instead to become one of them. She married Athaulf (“The Wolf”), the brother of Alaric, the king of the Visigoths. When Alaric died, a few months after the sack of Rome, Athaulf became the new king, and Placidia became the Queen of the Visigoths — a title that she always cherished. The couple had a child, a boy they called Theodosius, the same name as Placidia’s father, Emperor Theodosius. Placidia’s plan was as ambitious as a plan can be. She wanted to reunite Goths and Romans as a single people. They would have stopped fighting each other and lived in peace together.

As they say, the best plans of mice and empresses often gang agley. Placidia’s grand plan collapsed quickly. Young Theodosius died, Athaulf was killed in a palace conspiracy, and the Goths were defeated by the Romans who took Placidia back with them to Ravenna. There followed wars, battles, escapes, and acts of revenge in a story that reads like an adventure novel. Eventually, Placidia settled in Ravenna as Empress of Rome for 30 years, up to 450 AD, when she died at 62.

As far as we can say, Placidia was a good empress. While she was alive, the Romans always had food, and no Barbarian army dared to crash into Italy to sack and plunder. A judgment by a later chronicler, Cassiodorus, may say it all about her rule: "too much peace," even though it was intended as a criticism. Then, after she was gone, in a few decades, the Roman Empire disappeared into the dustbin of history.

By now, Placidia is almost a creature of the mythical universe of Gods and Heroes, just like Helen of Troy or the Guinevere or the Arthurian cycle. Yet, she has not yet vanished from our memory. Her voice is faint, but if we listen carefully, we can still hear it by visiting a small building in Ravenna that takes the name of Galla Placidia’s Mausoleum.

We cannot say for sure that the mausoleum was built on orders from Empress Placidia, but it may well be. And there are good reasons to feel Placidia’s presence in this building, even though she may never have been buried in it.

This building is like a woman who may show you something intimate of herself, but only if you deserve it. Simple and unprepossessing on the exterior, it is a triumph of colors inside. That’s already a message that comes from an age when whatever was beautiful and precious had to be kept hidden to be saved from destruction. But what you see in there is not just decoration. Everything has a meaning; it is in the figures and the images in it: it is her story, Placidia's story – that building will tell it to you, but only if you deserve it. If you walk in there in silence and you listen, you can hear her voice.

It is in the mausoleum that you can find a triumph of stars in the mosaics of the ceiling. Big, bright, fantastic stars that remind us of those painted by Vincent van Gogh. Maybe the same bright stars that Placidia saw as a young princess while traveling with the Visigoths in the first great adventure of her life.

Those stars remind us of how Christmas has been celebrated with “nativity scenes” for centuries in Southern Europe and Latin America. Of course, in the mausoleum, you won't find the baby Jesus and not even the Virgin Mary. Christianity, at that time, was different than what it is now. But the atmosphere of the nativity scene is there, with those bright stars which, in modern nativity scenes, were created by hanging a sheet showing a blue sky with big, silver-colored stars.

This is the message that Galla Placidia left to us: a message of hope. It comes from a time of wars, destruction, and much human suffering, not unlike our times. It comes from a person who experienced joys and tragedies and who saw her dream of peace between Romans and Goths shattered. But it tells us that no matter how things look bad, there is always a chance for a better future. A future that we may not see as individuals, but that’s there nevertheless. And hope is a gift that God gave us and that we must treasure as much as we can.

__________________________________________________________________________

Here is an image from Placidia’s mausoleum that may have been inspired by Psalm 42, “Sicut Cervus.”

It may be that Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina was inspired by this image when he composed his motet "Sicut cervus desiderat ad fontes" (as a deer desires a spring), one of the most beautiful pieces of polyphonic music ever composed. Of course, Galla Placidia couldn’t have heard anything like the polyphonic music of the European Renaissance, but I like to think that if she could hear this piece from where she is now, she could enjoy it as much as we do.

————————————————————————————

This text is a rewritten excerpt from a much longer discussion of Placidia’s life and deeds that I wrote in 2011. Let me also note that if you look for Galla Placidia on the Web you normally find this image said to be her.

It is not true. Among other things, this woman is wearing just one string of pearls, which indicates that she was not of the same rank as a member of the Imperial Family as Placidia. You can read the whole story of Galla Placidia in a post of mine.

Whence do we find a Galla Placidia to come forth in our own times? Do we see and focus only on woe in the world and discount hope and enchantment all around us?

"Christianity, at that time, was different than what it is now"

Indeed, yet as you suggest the journey to Nativity has been a powerful story since early times. I am indebted to Geza Vemes, Professor of Jewish Studies at Oxford, ('Christian Beginnings') for pointing out that 'This stress laid on a childlike attitude towards God is peculiar to Jesus."

I recently listened to a reading by Iain McGilchrist of a sermon on the Nativity delivered by Anglican Bishop Lancelot Andrewes, on Christmas Day 1622 in the presence of King James 1st of England & Scotland. It was an interpretation of the journey of the Magi and the guidance of the Day Star.

One Autumn nearly 50 years ago in a soundless night after a storm at sea and close to the darkest part of the shore of Crete, I looked out from an unglazed window to stars I had never seen before and have never seen since. You could almost touch them.

Van Gogh's starry picture is a brilliant introduction to the small building in Ravenna, and the ceiling.

Thanks. Have a good Christmas.

PS A story for another time is the project to deliver further debris and pollution into the upper atmosphere and its protective layers by multi 10s of thousand rockets to service 5G and perhaps an internet of things.