The Coming Population Collapse

The Most Catastrophistic Post I Ever Wrote

A few decades ago, it was widely thought that the whole world could become something like a Japanese subway station, crowded with huge numbers of people standing shoulder to shoulder. Today, however, everything has changed, and now we are starting to worry about the opposite problem: population collapse generated by pollution. We may call this interpretation “Carsonian,” as opposed to “Malthusian,” from Rachel Carson, known for her book “Silent Spring” (1962).

From the time of Reverend Thomas Malthus, in the 18th century, the future of human population has been a fashionable subject. It caters to two parallel and opposite crowds: the catastrophists and the cornucopians. The first sees population growth as a catastrophe that generates wars and famines, and the second as a blessing that will lead to continued progress and economic growth.

Remarkably, both catastrophists and cornucopians see the situation in Malthusian terms, with population growth an unavoidable phenomenon. The catastrophists see the population as limited by the available resources. Cornucopians do not deny this limit but believe that technology will always be able to increase food production, as demonstrated by the “wrong predictions” attributed to Malthus (not true, but that’s another story).

Could both views be partial, if not wrong? Could population growth be checked by factors other than a lack of food? How about the effect of pollution in the form of climate change, heavy metal poisoning, microplastics, and the like? We could call this kind of collapse “Carsonian” from Rachel Carson, who was among the first to point out the deleterious effects of pollution on the ecosystem and human health in her book “Silent Spring” (1962). So, are we facing a Malthusian collapse or a Carsonian one? Let’s see if we can use models to disentangle these two different possibilities.

Models of Population Collapse

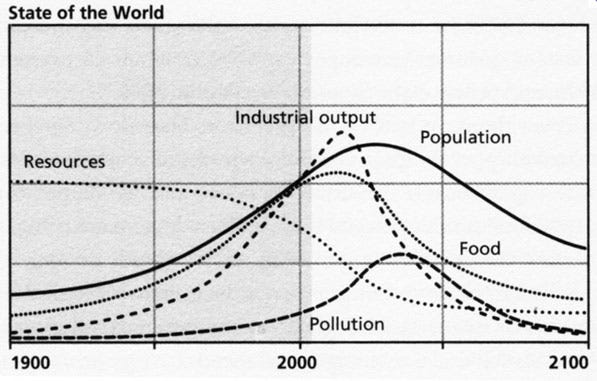

The “Limits to Growth” report, sponsored by the Club of Rome, was the first scientific study to attempt a quantitative description of global population trends. It was presented in 1972, but I am reporting data from the 2004 version—not very different, but more refined in terms of how the population is modeled.

This is the “base case” scenario, calculated for the available data and the hypothesis that the main trends of the world’s economy will not change in the future. Do not take it as a prediction; it is an illustration of a classic Malthusian population collapse, generated mainly by the decline of resources and the consequent lack of food. Note how the population curve is nearly symmetric; it grows, then declines at approximately the same rate.

Let’s see the results for different initial assumptions: a pollution-constrained (“Carsonian”) scenario.

The vertical scale in the diagram is the same as in the first one, so you can see that the initial amount of available resources has been doubled. In this case, the population grows more than in the resource-constrained model, but it goes down faster, constrained by the rapid increase in pollution. Note how both the “Population” and “Food” curves have taken the Seneca Shape, that is, they decline faster than they grow.

These results are general. I played with simple models (described in the appendix), and the results confirmed the “Limits” study. Here is an example:

This model assumes a purely “Malthusian” growth, that is, infinite resources. So, the population happily grows to create a huge source of pollution that then bites back hard, as you can see. You wouldn’t even call it “collapse.” It is more like being hit on the head by a sledgehammer.

To show that this is not just a theory, here is the data for a real case of population collapse: Ireland’s Great Famine, which started in 1845.

Here, the term “collapse” may be an understatement for a disaster that led Ireland to lose a quarter of its population in a few years. Of course, it was a local episode, and it compares only in part with the current global situation. We can say that it was, in large part, a Malthusian collapse. But it was also, in part, Carsonian in terms of being a tangle of feedbacks that involved a sickened population and a rapid reduction in birthrates. We don’t have such detailed data for most of the world’s historical famines, but in all cases, they are described as abrupt and devastating.

The current situation

Something is happening in the world that neither Malthus nor his detractors had expected. The world’s food production is approximately stable, and the global population is weakly growing. But human fertility has been going down like a falling brick. Just take a look at these data from a recent paper by Aitkens):

These are world averages, but natality is declining everywhere. The only regions where it is still high are in the central regions of Africa, but even there, it is rapidly declining. Here is the trend for a few regions of the world, still from Aitkens’ paper.

Different countries appear to follow similar trajectories, just shifted in time. African countries appear to be tailing Western countries while moving to lower and lower fertilities. Some projections indicate that if the present trends continue, humankind may go extinct in less than a century.

Pollution and the decline of fertility

The decline in fertility is almost always attributed to cultural factors, but many elements contradict this “official” explanation, pointing out chemical pollution as an important factor, perhaps the most important one.

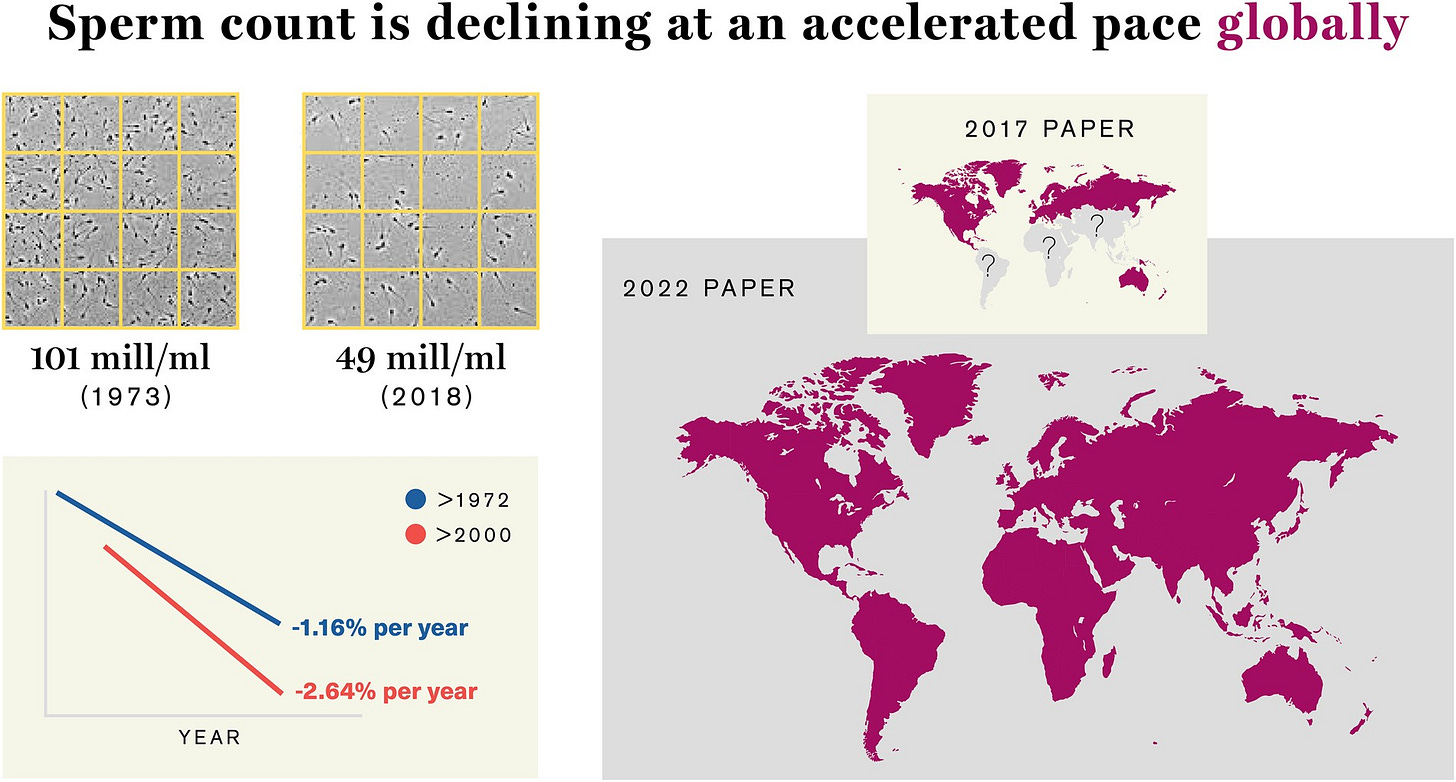

Pollution has a wide array of deleterious effects on human health. Direct evidence of how these effects cause a reduction in fertility comes from the decline of the sperm count in human males. The latest available data show that the average sperm count was halved during the past 50 years, and now it goes down by about 2.6% every year. If it maintains this trend, it will be reduced to around 10% of the 1973 value in another 50 years, but it is accelerating. You wouldn’t think cultural factors or egoism can change the sperm count. (source of the image)

Sperm count is a relatively easy parameter to measure, but it is just a flag for much deeper human health problems. The same is true for climate: Rising temperatures are relatively easy to measure, but they are a flag for much deeper problems of ecosystem degradation. The recent book Countdown by Shanna Shawn provides plenty of data on several ways in which the human reproductive system is being degraded.

Various pollutants, particularly endocrine-disruptor substances, are wreaking havoc on the delicate balance of human metabolism. Even CO2, often considered inert, is turning out to have negative effects on human health. It is not just a question of people not being able to reproduce; with your endocrine system degraded, you may not want to, having lost interest in sex and all related matters.

When dealing with complex systems, it is always difficult to disentangle the contribution of different factors that push the system in the same direction — it is true for the climate system, where CO2 is not the only culprit for global warming. It is true for the human population, where the reduction in fertility can’t be linked to a single socioeconomic or biochemical factor. What we can say is that fertility is going down at a dramatically fast pace, and we should develop some kind of strategy to face it that takes both possibilities into account.

What to do?

Unfortunately, as with all the problems that our beleaguered humankind is facing, fertility decline is often interpreted in political terms, and politics doesn’t know nuances. So, the “Carsonian” interpretation based on pollution is often vehemently rejected because it goes against the grain of current political views. Growth is believed to be always good, so it is unthinkable that the growth of the economy could destroy the economy.

In politics, the solution to a problem is often found by locating a culprit. In this case, it is easy to fault women, and people in general, for not wanting children because of their egoistic and hedonistic attitude. Hence, it is commonly believed that it would be possible to reverse the trend through appropriate social and economic interventions to encourage families to have more children. So far, though, this idea has been an abysmal failure, as described, for instance, by “The Financial Times.”

Maybe we just need to spend more money on convincing people to have more children? Maybe, but do not forget the Easter Island fallacy: “The problem will be solved if we just build bigger statues.” Following this line, someone will eventually propose forbidding women from going to school, firing them from their jobs, removing all appliances from their kitchens, and things like that. After all, when women stayed home and worked in the kitchen, they had plenty of children, didn’t they? Incidentally, the COVID-19 pandemic generated a measurable uptick in the number of births in the US about nine months after the first lockdowns. Could someone propose that locking people inside their homes again would help solve the fertility crisis?

What if, instead, we are facing a “Carsonian Collapse,” generated mainly by pollution? That’s much less attractive in political terms because 1) there is no culprit except all of us, 2) the collapse is expected to be not just rapid but brutal, and 3) there are no easy, low-cost solutions (note how all these three conditions perfectly describe also the problem of global warming).

Usually, humans are much better at countering Malthusian problems of resource scarcity than Carsonian ones of increasing pollution. Think of how fracking technologies successfully delayed the Hubbert Peak of oil production by at least one decade. In agriculture, over the past several decades, we have increased the crop yield fast enough to compensate for population growth. Think about how the new technology of precision fermentation promises to make traditional agriculture as obsolete as the stone axe.

But humans are much less efficient when it is question of fighting pollution. Not that there aren’t success stories at the local level, and it has indeed been possible to eliminate at least some major deadly pollutants: lead, cadmium, beryllium, CFCs, DDT, and others). However, we have had little or no success in other cases, such as stopping the emissions of substances that enormously damage humankind and the whole ecosphere. Think of carbon dioxide, pesticides, endocrine disruptors, “forever chemicals,” and more. Abating the pollution that’s destroying human fertility looks like an impossible task, considering the enormous resistance offered by the industrial lobbies. Just note the recent failure of the Global Treaty on Plastic Pollution. As for climate change, much talk but no results.

Global problems are more likely to generate technologies that work on the symptoms rather than on the problem. In climate change, these are the various “climate engineering” ideas. About the obesity pandemic, it is the miracle drug Ozempic (maybe not such a miracle). And, about the fertility collapse, we might use in-vitro fertilization and similar things — we are already using them. It is unlikely that they could change the fertility decline, but they would ensure the survival of at least a fraction of humankind: those who can afford them.

Perspectives

The fertility collapse is rarely recognized for what it is in a world where the cultural sphere tends to operate according to obsolete perceptions. One is the Malthusian view that we have an “overpopulation problem” that needs to be solved by increasing food production. At the same time, we need more cars, more planes, more homes, more TV sets, and more things of all kinds — it is the meme of economic growth that has driven human society during the past 2-3 centuries. Instead, we will soon face a completely different social and economic situation.

It is not that fertility collapse is a good thing, but it could make the problems related to resource depletion and climate change less dramatic than they appear to us now. But note that there are still plenty of chances for exterminations and climate-related disasters as long as the population decline has not started yet. Even when it starts declining, it will bring all sorts of problems, including clashes between populations at different stages in their decline curve. We saw a hint of these possible clashes in the debate during the latest US presidential elections.

Whatever the case, the clash between catastrophists and cornucopians may soon end in irrelevance, just like that between Guelphs and Ghibellines in Medieval Europe. Our ideas change as we try to understand the future, but only the Universe has all the data and the good models. It continues to compute itself as it moves toward the future, uninterested in what we humans think.

__________________________________________________________________

Appendix: Equations for system dynamics models of population trends.

Malthus (P=population)

dP/dt= k1P

Verhulst: P= Population

dP/dt= k1P(1-P)

Hubbert: R= resources, P= Population

dR/dt = -k1PR

dP/dt = k2PR -k3P

Carson. P=Population, W= Pollution (Waste)

dP/dt= k1P -k2PW

dW/dt =k3PW-k4W

Seneca. P=Population, R=Resources, W=Pollution

dR/dt = -k1PR

dP/dt = k2PR -k3PW

dW/dt=k4PW-k5W

You are talking about chemical pollution (which may indeed play a role), but there are plenty of other kinds of pollution. Light pollution and sound pollution come to mind. Might constant noise and a lack of night darkness make people less interested in sex and child raising? And then there's the issue of overcrowding. I have long suspected that the fertility collapse that we are observing is caused to quite a significant extent by our mammalian instinct against overcrowding. It would go a long way toward explaining why fertility is cratering all over the world, despite major differences in culture. Because all those cultures have one thing in common: urbanization and (therefore) overcrowding inherent in city living.

Statistical data shows that last year of population growth in Serbia was 1991 (0,2%). From that year there is steady decline which is accelerating. Currently Serbia loses between 40 and 50 thousand people per year, a colossal decline for a country of 6,5 mil. I think that in Serbia's case Seneca cliff is proven fact.