The Collapse of the US Elite

It is a full-fledged revolution!

It is the destiny of all elites to be born as saviors and die as parasites. The US elite may be going the same way that the old Soviet Communist Elite went: condemned by its inefficiency and pushed out to make space for another elite. It was expected, although not so soon. The attempt may still fail, but one thing is clear: this is a revolution.

“Popular Revolutions” aren’t

The adjective “popular” is often attached to “revolution.” And indeed, in their hot phases, revolutions often see a consistent participation of “the people.” But history shows that their role is mostly that of musket fodder.

A revolution may delude people into thinking that they are taking power into their own hands, but the final result is the replacement of an old elite with a new one. Think of how the French got rid of their king in 1793; then, little more than 10 years later, they had an Emperor (Napoleon) in exchange. Think of the Russian revolution. Lev Tolstoy gives us a magistral portrait of the Tsarist elite in the mid-19th century in his “Anna Karenina” (1877): a band of parasites interested in nothing but money and self-promotion. They were swept away by the Communist Revolution in 1917. But it would be hard to say that workers were ever in power in the Soviet Union. Rather, the government was managed by a new elite sometimes called the “Nomenklatura,” in turn swept away by a new revolution in 1991.

Elites are indispensable for the functioning of the state and, no matter how we may reason that a perfect society shouldn’t need an elite, we can’t find a real one in history that was “eliteless.” The problem is that all human organizations tend to become inefficient, costly, and often counterproductive, showing “diminishing returns to complexity,” as Joseph Tainter noted. You can say that they accumulate entropy; it is typical of complex systems. (See at the end of this post some mathematical models of this story).

The problem is especially serious when the economic system is undergoing a contraction: military stress, resource depletion, pollution, and more, reduce the capability of the system to sustain its elites. Then, the elites become a huge parasite sucking out vital resources from the rest of society. The size of the elite class has to be reduced, but the elites are not good at that; they have no structures to cut down their own number. In practice, they keep growing until they cease to be useful and become a burden for society.

The results are known: a top-heavy social structure, the ruthless exploitation of the poor, the diffuse inefficiency, the brazen injustice, and more. It all tends to generate a police state where the elites desperately try to maintain their power using force. It can’t normally last for long: by beggaring commoners, the elites destroy their source of wealth, and the result is collapse. In states, collapse is normally traumatic, and it involves a lot of violence, blood, and destruction. In corporations, it is called “corporate restructuring.” It is not, normally, bloody, but it is surely traumatic for those being restructured.

The current situation in the US is a clear example of the start of a revolution. The old US elite, aka the “deep state,” has become too large, too inefficient, too parasitic, and too violent. It has to be replaced with a new one. It has been surprisingly fast, but it is happening. The momentum of the “Magaist” revolution is tremendous, and the opposition is reduced to little more than old leftists yelling at clouds. It may still not succeed, but the mechanism is clear.

The US and the USSR — Similar elite reshuffling

The current situation of the US looks remarkably similar to that of the collapse of the USSR in 1991. Dmitri Orlov already noted in his Reinventing Collapse (2008) how the two superpowers had similar social and economic structures and that, hence, they had to follow similar paths toward collapse.

In the USSR, the state was in the hands of a clique of oligarchs who absorbed most of the state’s resources. The collapse arrived shortly after the retreat from Afghanistan, which had taken a heavy toll on Soviet resources. A little more than 30 years later, the US retreated from Afghanistan as well, although their unwinnable war may be more the conflict in Ukraine. In any case, the US is also in the hands of a bunch of parasitic oligarchs who don’t seem to be doing anything except funneling the country’s wealth into their bank accounts. Similar conditions lead to similar outcomes.

Note also that the elite shuffle in the USSR corresponded to the stalling of Soviet crude oil production. Today, the US elite shuffle is taking place exactly when the peak of shale oil is arriving. We’ll have to wait to see whether shale oil is really facing a phase of terminal decline, but it may well be the case. Reduced oil production constrains the system's economic output, highlighting the need for an elite shuffle. And that’s how certain things happen.

Revolutions are unavoidable but not good.

Revolutions may be unavoidable, but they are not good things - rarely bloodless. The ongoing one in the US has incredible forward momentum but also plenty of chances to fail. The old elites still control the US military apparatus: they may decide to do nothing, as the Red Army did in 1991, or they may decide to use force to stop Trump and his followers. Tanks rolling in Washington? Why not? History rolls when it decides to. Or more simply, the revolution may lose its momentum because of internal squabbles, or a determined resistance by some of the old elites. In these cases, the problems with the overexpanded US elite will be postponed but not solved. Waiting too long before reforming the system is the recipe that leads to an even worse Seneca Collapse.

The new Elite taking power in Washington seems to be mainly a group of technocrats who earn their wealth and power by controlling the Internet and the communication system in the West. They come together with an ideology, “Magaism,” that carries a nasty streak of violence and racism. Fortunately, our times seem to be a little less violent than old ones. We may see plenty of heads rolling in the near future but, hopefully, only in a virtual sense. The old oligarchs will be told to retire to their mansions and stay quiet. And they will be very happy to have gotten off so lightly!

In any case, apart from Trump’s unhinged ramblings and his followers’ mad proclaims, the US badly needs to abandon its imperial ambitions, reduce its military presence overseas, concentrate its resources on its territory, and rebuild an economic system that doesn’t depend on robbing other countries. Whether that will be possible is all to be seen. Russia succeeded at doing that, but it was not painless for the Russian people. Not at all.

The biggest risk: the collapse of the US scientific research system

One specific risk of Magaism is the collapse of the US scientific research system. The MAGA ideology carries with it a strong anti-science streak. This is understandable: the research system in the US and the West has evolved with the rest of the government bureaucracy, becoming a bloated and inefficient system that mainly wastes public money to enrich bureaucrats and assorted parasites (most scientists are the underpaid and exploited peons of the system).

Surely, the research system badly needs radical reform. At the very minimum, it needs to regulate the interactions between academia and industry, which often result in scams to sell useless (and sometimes harmful) products to the public. To say nothing of the scandal of the scientific publication system. It works by having scientists use public money to pay publishers to take control of work made with public money that they then proceed to resell, siphoning even more money from the public. And there is more, but let’s not go into the details.

The risk is that the reform of the scientific research system will not be just a reform but a wholesale takedown obtained by defunding (it is already happening). That would be a disaster because you can’t freeze-dry scientists and rehydrate them when needed. When scientists stop doing research for more than a few years, they become obsolete and useless, very difficult to re-train and insert back into the system. So, we risk losing the competency built in several decades of work. That’s especially true for areas that Magaists find objectionable, including pollution control, climate science and ecosystem studies. So, we would lose the very tools we need to understand what’s happening and what is likely to happen in the near future.

Something similar happened to the Soviet research system, defunded and neglected for more than a decade. Soviet scientists had to abandon their research, move abroad, or become bank employees or janitors. Fortunately, Russian science managed to recover and return to the earlier levels of excellence, but it was a hard blow. Will the West be able to avoid this destiny?

Models of Revolution

A way to see the collapse of the elites is to consider them as “predators” of the lower classes, (the “preys”). You can use simple mathematical models of the kind developed long ago by Lotka and Volterra to show that the predators tend to go in “overshoot.” They deplete their prey so badly, that the can’t sustain themselves any longer, and then they have to crash down. That happens fast according to the “Seneca Effect.”

Here are two of the articles (slightly edited) that I published in 2014 on “Cassandra’s Legacy” commenting on the role of the elites in the trajectory of an economic system. They illustrate how it is possible to model the growth and decline (more like collapse) of the elites. Incidentally, I am not writing any more on that blog because it was de-platformed by the Googlish powers that be. In itself, it is a good illustration of how power comes today from the control of the information flow.

Why the elites are so ruthless that they destroy themselves

The recent announcement of a paper by Motessharrey, Rivas and Kalnay (MRK) on the collapse of complex societies has generated much debate, especially with the publication of an enthusiastic comment by Nafeez Ahmed, who defined it a "NASA-funded" study. The term rapidly went viral - no matter how irrelevant the source of funds for the study is - and the discussion soon veered to the kind of clash of absolutes that took place after the publication of the first report to the Club of Rome, "The Limits to Growth" of 1972. For instance, a rather heavy-handed criticism of the study can be found in a post by Keith Kloor.

Apart from these rather predictable reactions, what can we actually say of this study? Is it really saying something new, or is it just another "cry wolf" study? Let me try a brief appraisal.

First of all, the MRK study is firmly grounded in system dynamics (even though the authors don't use the term in their paper), the method of modeling created in the 1960s by Jay Forrester. It has also many elements in common with the models used for the original "The Limits to Growth" study of 1972, and the subsequent updates. However, it is a simpler model which makes no attempt to compare the results with historical data. In this sense, it is similar to the "mind sized" models which I have been discussing in a paper of mine on "Sustainability".

Going into the details, we see that the MRK model is a simple, four-stock model. One is the "Natural Resources" stock, which is gradually transformed into the stock that the authors call "Wealth" (which in other models is called "capital"). The other stocks are the two classes of the population: "commoners" and "elite". Both take their subsistence from the "wealth" stock, but only the commoners replenish it. The elites, instead, do not produce anything.

The results are not unexpected. Depending on a variety of possible initial assumption, the system may reach a steady state, oscillate, or show a series of peaks and collapse. The figure below, from the MRK paper, is the result that most looks like the "Limits to Growth" "base case" scenario - except for the fact that the population stock collapses in two phases rather than in a single one.

Here, the MRK model is telling us no more than previous studies did, such as qualitative models (e.g., Catton's "Overshoot" and Hardin's "The Tragedy of Commons") and quantitative ones such as "The Limits to Growth". In most cases, this subdivision of the population in two stocks doesn't change very much the results of the model in comparison to single stock ones (also reported in the MRK paper). But in some cases, the authors observe rather surprising results, such as this one:

As you see, here, society literally commits suicide by having the elites draw so much wealth from the accumulated resources that nothing is left to commoners - who die out. But the elites don't produce anything, and therefore the wealth stock disappears. The final result is that the elites are so ruthless that they destroy themselves.

Note that in this scenario, the natural stock recovers its initial level: collapse is not the result of a lack of resources but of the inability of society to access them. It is a result that eerily reminds a possible interpretation of the collapse of the Roman Empire. The Romans may have directed so much wealth to non-producers (the army) that producers (slaves) nearly disappeared. Since there was hardly anyone left to cultivate the land and, eventually, the whole society collapsed.

Of course, this is an interpretation that needs some caution. One reason is that in the MRK model, commoners cannot become an elite, and elite members cannot become commoners; the two classes are completely separated and impermeable to each other. This is surely an oversimplification: before dying out completely, the elites would at least try to learn to produce something. On the other hand, however, government bureaucrats make very bad peasants.

Possibly, a more important shortcoming of the MRK model is that it lacks the critical parameter of persistent pollution, which is present instead in the "Limits to Growth" model. Pollution, if it were considered, would likely play a fundamental role in this "labor shortage" scenario. In any case, these considerations illustrate the power of models to stimulate the interpretative capabilities of the human mind. We don't need any formal model to describe the final destiny of economic systems that grow on overexploiting the resources they use. In time, they must go back to a condition compatible with the available (remaining) resources. Most models tell us that this "return" happens as the result of a cycle of overshoot and collapse, which is indeed a characteristic pattern of those socio-economic structures we call "empires"”

The MRK model has highlighted a factor that so far has been scarcely explored: how the unequal distribution of wealth affects the trajectory of an economic system in overshoot. This is an important parameter because, in this period, we see an epochal transfer of wealth from the lower classes of society to the elites. Whether this phenomenon will accelerate collapse or slow it down, we cannot say. But, surely, it is something we need to study and understand.

________________________________________________________________________

How to destroy a civilization

This is the third post of comments on the "NASA-funded paper" (a term that went viral) on societal collapse by Motesharrei, Rivas, and Kalnay (MRK). In my first post on the subject, I noted some qualitative features of the model. In the second post, I commented on the debate. Here, I am going more in-depth into the structure of the model, and I think I can show that the results of the MRK model are very general as they can be reproduced with a simpler model. In the end, it IS possible to destroy a civilization by spending too much on non-productive infrastructures - such as the Moai of Easter Island (image above from Wikimedia, Creative Commons license)

Mathematical models may be a lot of fun, but when you use them to project the future of our civilization, the results may be a bit unpleasant, to say the least. That was the destiny of the first quantitative model, which examined the future of the world system. The well-known "The Limits to Growth" study was sponsored by the Club of Rome in 1972. This study showed that if the world's economy was run in a "business as usual" mode, the only possible result was collapse.

This kind of unpleasant result is a feature of most models that attempt to foresee the long-term destiny of our civilization. It should not be surprising, considering the speed at which we waste our natural resources. Nevertheless, whenever these studies are discussed, they generate a lot of criticism and opposition. It is the result, mainly, of emotional reactions: there is nothing to do about that; it is the way the human mind works.

But let's try to put aside emotions and examine a recent study by Motesharrei, Rivas, and Kalnay (MRK) on the destiny of human society that became known as the "NASA-funded model" after a note by Nafeez Ahmed. The model has attracted much criticism (as usual), but it is worth looking at it with some attention because it highlights some features of our world that we should try to understand if we still think we can avoid collapsing (or at least mitigate it).

The MRK model has this specific feature: it divides humankind into two categories, "commoners" and "elites" assuming that the first category produces wealth while the second is a parasite of the first. In some assumptions, it turns out that the elite can completely drain all the resources available and bring society to an irreversible collapse, even though the resources are renewable and can reform the initial stock.

I think this is a very fundamental point that describes events that have happened in the past. As I noted in a previous post, it may describe how the Roman Empire destroyed itself by excessive military expenses (we may be doing exactly the same). Or, it may describe the collapse of the society of Easter Island, with a lot of natural capital squandered in building useless stone statues while putting a high strain on the available resources (the story may be more complex than this, but its main elements remain the same)

So, it looks like elites (better defined as "nonproductive elites") may play a fundamental role in the collapse of societies. But how exactly can this be modeled? The MRK model uses an approach that, as I noted earlier on, is typical of system dynamics (even though they do not use the term in their paper). Not only that, but it is clearly a model in the style of those "mind-sized" models that I proposed in a previous paper. The idea of mind sized models is to avoid a bane of most models; that of "creeping overparametrization." Since, as a modeler, you are always accused that your model is too simple, then you tend to add parameters over parameters. The result is not necessarily more realistic, but surely you add more and more uncertainty to your model. Hence, the need for "mind-sized" models (a term that I attribute to Seymour Papert)

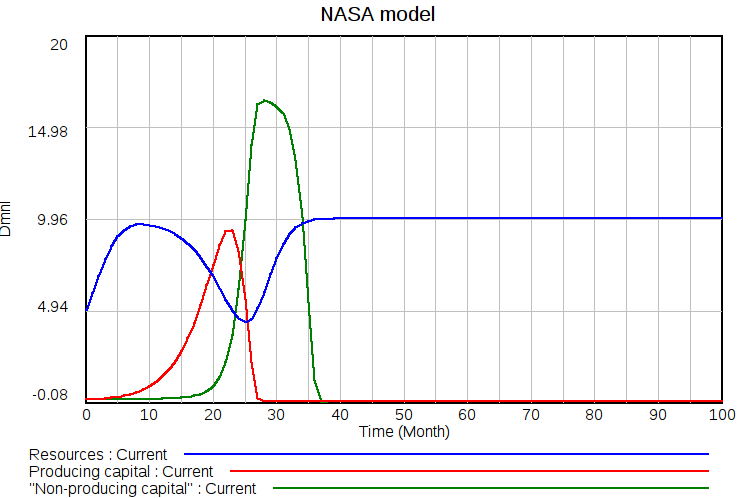

So, let me try to rework the MRK model, simplifying it a little and making it more streamlined. Instead of speaking of "elites" and "commoners," let us speak of two different kinds of capital. One kind we call "productive," and the other "non-productive” Capital is the result of the exploitation of natural resources. "Productive" capital is the kind that leads to further exploitation and growth of the economy; the other kind is simply wasted.

Let me explain what I mean with the example of Easter Island's economy. Productive capital is the agricultural structure, while non-productive capital is the Moai building structure. Agriculture sustains people, who then can grow and cultivate more land. Moai building doesn't do anything like that—it is a pure waste of resources and human labor. In our times, we can say that productive capital is everything that exploits the available resources, from refineries to fishing boats. Non-productive capital is everything else, from private yachts to battle tanks.

Can we build a model that includes these elements? Surely we can; here is a version of the model in the style of "mind-sized " models (done using the Vensim software).

The model is a streamlined version of the MRK model, where I added a "pollution" stock (missing in the MRK model) and simplified the productive cascade structure. It would take some time to explain the model in detail, and there is not enough space here. If you want to go more in-depth into this subject, you can read my paper on "Sustainability" or this post of mine with the rather ambitious title "Peak Oil, Entropy, and Stoic Philosophy." But, please understand that the model, though very simplified, has a logic; what it does is to describe the degradation of the thermodynamic potential of the starting resources (the first box, up left) into a series of capital reservoirs which, eventually, dissipate it in the form of pollution. The "kn" constants determine how fast capital flows from one stock to another. The arrows indicate feedback: we assume here, for instance, that the production of industrial capital is proportional to the size of both the resources and capital stocks.

Now, let's go to the results obtained with some values of the parameters. Let's take r1=0.25, k1=0.03, k2=0.075, k3=0.075, k4=0.05. The initial values of the stocks are, from top to bottom, 5, 0.1, 0.1, 0.01 - you may think of the stock as measured in energy units and the constants in energy/time units. With these assumptions, the model produces the same phenomenon that MRK had observed with their model. That is, you observe the irreversible collapse of the system, even though the natural resources reform, becoming abundant at the beginning of the cycle.

You see? Producing and non-producing capital ("commoners" and "elites") both go to zero and disappear. Note how natural resources return to their former value, but the elites and the commoners don’t. This civilization had destroyed everything and won't restart to accumulate capital again for a long, long time. Note also how these results depend on the assumption that non-producing capital cannot be turned into producing capital. It may be a drastic simplification, but it is also true that turning swords into plowshares is a nice metaphor but not something easily done in the real world.

At this point, let me say that this post is just a sketch. I can tell you that it took me about 15 minutes to write the model, a few hours to test it, and about one hour to write this post. So, these considerations have no pretense to be anything definitive: the model needs to be studied in more detail. When I have time (and as soon as I can fix my cloning machine), I would like to write a full paper on this subject (anyone among the readers would like to give me a hand? Maybe someone with a better cloning machine than mine?).

Nevertheless, even though these results are only preliminary, the fact that the MRK results are so easily reproducible indicates that they seem to have identified a feature that most models have neglected so far. Although you can always accumulate capital by exploiting natural resources, the final outcome depends a lot on how you spend it. The model tells us, for instance, that a popular recipe to "save the economy" by "stimulating consumption" may actually destroy it faster.

So, are we destroying ourselves because we are wasting our natural capital on useless tasks, from battle tanks to SUVs? (and lots of bureaucracy and an overblown financial system, too). Are we destroying our civilization by building these useless structures just as the Eastern Islanders destroyed themselves by building Moai statues? It is something we should think about.

Note 1: I think this model has a lot to do with Tainter's idea of the "declining returns of complexity, if we take "complexity" to mean that lots of resources are used to build something that produces nothing. I already tried to model Tainter's idea with a mind-sized model in a previous post of mine and I am sorry to see that Tainter didn't like so much the MRK model. But I think it is mostly a question of different languages being used. If we work on communication, I think it is possible to find a lot of points of contact in the different approaches of modelers and historians.

Note 2. Doesn't this model contradict the conclusions of my book "Extracted", that is, that our society is collapsing as a result of the depletion of mineral resources? No, it doesn't. The parameters I used for the run shown here are chosen to reproduce the results of the MRK paper, which assumes that resources are fully renewable. You can run this model in the hypothesis that resources are NOT renewable, which is an assumption closer to our situation. In this case, the model will tell you that the system will collapse leaving unused a large fraction of these theoretically exploitable resources; the larger the more overblown the non-productive capital stock will turn out to be. This is something that I think is very relevant to our situation: we saw it happening with the financial crisis of 2008, and the next financial crisis, I believe, will generate this effect again. (h/t Tatiana Yugay)

We do have a precedent to Trump and MAGA in Mao's Cultural Revolution. The techniques are more sophisticated but the goals are eerily similar: Attack elites (expertise) to eliminate or at least disarm those who can challenge your power. Simultaneously convince the "commoners" that this attack is in their interest, and the tools to spread such propaganda have grown enormously. The underlying requirement is that the vast majority of commoners have little or no appreciation of where all the good stuff comes from, i.e., everything from energy to food on supermarket shelves to modern medicine, so we take it all for granted. The new elite (Musk being the poster child) are taking full advantage of these disconnects, and trying to widen them through control of new media. Certainly there is bloat and overshoot in the current regime but I think these yawning disconnects, a symptom of Tainter's energy-complexity spiral, is the most important change driver. Sadly, if the next elite replacement cycle does occur, it will take the checks and balances of US democracy with it as collateral damage.

Your article highlights the problem with human nature, and the problem with human nature is human nature.