In a chess game, if the king dies, his army disbands. But the real world is a little different, and there may hold the law I call “The Flying Keystone;” an isolated leader is as good as a dead leader. This may be the key to the fall of Assad’s government in Syria.

Let me start by stating that I don’t pretend to be a citizen of the Syrian Punditstan, whose inhabitants have been discussing at length the collapse of the Syrian government producing a variety of explanations, mostly in conflict with each other. But, as you know, I am interested in systemic collapses, specifically the “Seneca Collapse,” which occurs when multiple feedbacks act together to bring the system down. As I wrote in my 2017 book, “The Seneca Effect,” an army is a special kind of complex system, a hierarchical one, subjected to rapid collapses even more than the standard complex systems existing in nature. So, let me try to discuss the Syrian collapse in systemic terms.

Armies as hierarchical networked systems.

Most complex systems in nature are “scale-free” networks that lack a central command and control system but rely on local connections to form communication hubs of various sizes. These networks are very resilient; they tend to reorganize when perturbed and maintain their main functions. However, they are not made to do the job of an army, that is, fighting as a single unit. The first imperative in the natural world is survival, and most natural networks have evolved to maximize that goal.

Think of a herd of buffalo, a simple example of a non-hierarchical network. When facing a threat, the feedback mechanisms of the system enter into play. A buffalo starts to run, others follow, and soon, the whole herd is running away from the threat. An army can behave the same way when a soldier starts running away: the others may follow his example. For both individual buffaloes and human soldiers, following the stampede is the best survival strategy. But if the soldiers flee, the army does not fight. The military version of the Seneca collapse has been the nightmare of generals in history.

That’s why armies are organized hierarchically. The rigid pyramid formed by their command and control system is thought to avoid catastrophic collapse. It is said that at the time of Bismarck, Prussian soldiers were trained to be more afraid of their officers than of the enemy. They knew that if they tried to run away from the battlefield, they would be shot by their officers and that their only way to survive was to defeat their opponents.

But a hierarchical army can collapse, too. It just shifts the collapse problem from the base to the vertex. If the vertex is destroyed, then the whole network collapses. Any structure organized in this way is subjected to what we call nowadays a “decapitation strike.” As in a chess game, kill the King, and the whole army stops fighting. In Syria, the leader, Bashar el-Assad, was not a king, and he was not killed, but he was unable to lead and gave up his position almost immediately. The collapse of the Syrian army followed.

The Collapse of the Kingdom of Naples

To discuss military collapses, we could start by examining historical cases. One was how the Italian army ceased to fight and disbanded in 1943 when the King of Italy ran away from Rome, leaving the army without orders and leaders. A less well-known case is the collapse of the Kingdom of Naples in 1860 (more precisely, the “Kingdom of the Two Sicilies”) when attacked by an army from Piedmont led by Giuseppe Garibaldi.

This story is scarcely known outside Italy, and when it is, it is heavily filtered by nationalistic propaganda that portrays Garibaldi as a heroic freedom fighter who liberated Southern Italian citizens from the heavy yoke of the evil Bourbon dictatorship. As you may imagine, the reality was considerably different.

The fall of the kingdom of Naples was the result of the great game of empires of the mid-19th century, which the British played masterfully. At that time, Britain faced France as its main competitor on the world chessboard. By annexing Algeria in 1830, the French made a strong move, a step toward creating a French Mediterranean Empire. As a consequence, a crucial strategic priority for the British was to block France’s expansion in the Mediterranean theatre.

The British bet on the growing power of Piedmont to unify Italy under a single government and turn the country into a local power that could stop France’s expansion. They financed a military adventurer, Giuseppe Garibaldi, who gathered an army of a thousand volunteers and invaded Sicily in May 1860 with the idea of bringing down the Kingdom of Naples. That would allow the King of Piedmont to seize the whole Italian peninsula. In a few months, Garibaldi defeated the Neapolitan armies and took the capital, Naples. The allies of the Kingdom, the Russians, had been defeated a few years before in the Crimean War and couldn’t intervene. The Neapolitan king, Francis II, fled, taking refuge in Rome. The unification of Italy under the Piedmontese Kings would be officially declared one year later.

The similarities with the current events in Syria are many: in both cases, a weak state was overthrown by a small army financed by a powerful overseas empire. In both cases, the king/state leader could not lead an effective resistance. Let me list the roles in these two chess games, one ancient and the other recent. The correspondence is nearly perfect.

The Flying Keystone

What caused the Kindom of Naples to fall so fast and easily? Was it just the king's weak personality? In part, this is possible, but it cannot be the only factor. Another factor that probably played a fundamental role was corruption, which weakened the Neapolitan military network.

Nearly two centuries after the events, the extent of the role of corruption in Garibaldi’s victory remains politically charged and impossible to prove. For what we are discussing here, though, let’s just say that the use of corruption in Garibaldi’s campaign makes sense in light of the economic unbalance that separated the Kingdom of Naples from its Piedmontese and British enemies (I discuss here the reasons for this unbalance). Bribery may not have been just monetary but may have involved promises of a new career. We know that several Neapolitan generals served in the Italian army after the defeat.

In network terms, the layered structure of a hierarchical army makes it possible to obtain the same result as eliminating the king by disrupting the function of one of the intermediate layers. If the king cannot communicate with the army, he is effectively eliminated from the game: it is checkmate.

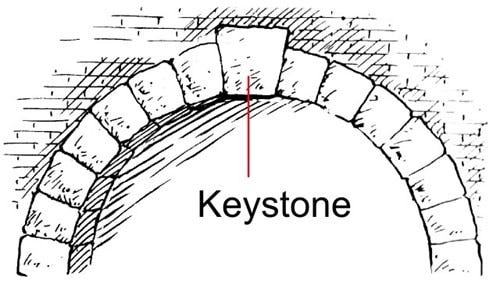

I call this strategy the “flying keystone.” You know that a stone arc is kept together by a keystone. Remove the keystone, and the arc collapses (another example of Seneca Collapse). But you can obtain the same result by eliminating the stones close to the keystone. The resulting “flying keystone” will fall by itself. Lawrence J. Peter calls it “the flying apex,” meaning the same thing, it is part of the idea of the "Peter Principle.”

My impression is that the flying keystone strategy could be common in modern and ancient history. For instance, Benito Mussolini, the Italian duce, started his career as a shill for the British secret services, and he may have been maneuvered by the British throughout his career, although indirectly. Isolated at the top by a layer of sycophants — perhaps corrupted by the British — Mussolini lost contact with the real conditions of the army, and that was one of the reasons for his incredible mistakes that led Italy to be badly defeated in WWII. Of course, I have no proof for this interpretation. I can only propose it in a fictional form in my novel, “The Etruscan Quest.”

There may have been several more cases in which the bribery of the leader's entourage led to his downfall. And it seems that the Syrian President, Bashar El-Assad found himself isolated from its army, discovering only at the last moment that he had been betrayed by his generals.

The Future of Syria.

Apart from general considerations on the mechanism that led to collapse, the similarity between the case of Syria and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies allows us to try to peek into the future. Does Syria face the same destiny as its ancient Italian mirror? If it does, it is not a bright destiny. Although Garibaldi’s campaign was not especially bloody, the aftermath was a civil war that pitted the Italian Army against the remnants of the Neapolitan Army who had reorganized and were fighting a guerrilla war against the invaders. It lasted several years until the revolt was quelled by a harsh repressive campaign. The result was the massacre of thousands — perhaps tens of thousands — of Southerners, including many civilians caught in the deadly repression mechanism. Still today, these events are deeply felt in Southern Italy. I tell this story in some detail in my book “Exterminations”

Does Syria face the same destiny of civil war and massacres? From what we have been seeing those few past days it seems that it is perfectly possible, unfortunately.

In this post, "Initiatives", I excerpt and link to a lot of views of the filling of the Syrian power vacuum now underway. Turkey wants it all, reconstituting the Ottoman Empire. Israel wants a little-more and a little-more and a little-more as long as it is free of IDF blood, and is encroaching quite well, despite being warned off by somewhat distant Turks. HTS holds Damascus and major cities along the north-south line, but with a fairly small and dispersed force.

Russia moved away from Kurdish areas, contested by Turkey, and Russian/Syrian-army bases are being taken by scanty US forces to deter Turks. Turks say Kurds in Syria are an existential threat and they will militarily evict them from the best farmland and oilfields.

https://drjohnsblog.substack.com/p/initiatives

In the case of Syria, it's borders were artificially drawn by foreigners in such way that several opposing ethnic groups were fused together. Such countries are notoriously difficult to keep together even in the most favorable circumstances. Italy, on the other hand, has common foundation that is Italian language (with several dialects). Therefore there was some logic in making Italy unified country. British just facilitated the unification for their strategic reasons but Italy later became British enemy much more powerful than Kingdom of Naples could ever be. No matter how good British are in their machinations it's always risky strategy. The centuries of machinations are not helping them now when they are falling fast.