Leaving Facebook for good takes a certain amount of time and effort. For me, it seems to be going well; just deleting the FB app from my cell phone has done wonders. Then, I keep a presence for now, but only occasionally. But the real point is to see whether Facebook will actually crash, as I proposed in a previous post. Above, Lucius Seneca amiably discusses with Mark Zuckerberg in the Roman Forum. (image by Dezgo.com).

Is Facebook going to fold over and disappear? Could the big beast shrink to nothing in a short time? In a previous post, I compared the Facebook growth curve with that of its predecessor, a forgotten platform called “Friendster” that disappeared in 2009, going through a classic “Seneca Cliff.”

I argued that Facebook was slated to follow the same curve, collapsing in the coming years. But why should that happen? In this post, I explain how complex systems (and Facebook is one) tend to grow and collapse according to the laws governing “memes” according to a scientific field called “memetics.”

In his 1976 book “The Selfish Gene,” Dawkins coined the term “meme” to describe a unit of cultural transmission, drawing an analogy between cultural and biological evolution. Memes could be anything from tunes and ideas to fashion trends, and they replicate through imitation in a manner similar to how genes replicate in biological contexts. The term “meme” is not yet used so much in the current scientific literature, but when people say that a certain concept has “gone viral” on the web, they are implicitly using it. So, we could replace “meme” with “virus of the mind” or, simply, with “idea.” But we are talking of the same thing.

The whole point of memetics is that memes are not rational, they are not fact-based, and they do not necessarily have a connection with the real world. They are built to diffuse in the minds of their hosts (us), and those memes that are best at that are those that survive and diffuse. Memes populate a virtual reality where natural selection operates in Darwinian terms.

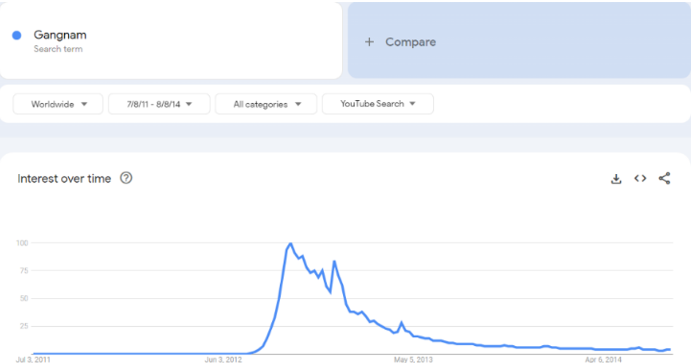

Most memes are harmless; we call them fads or fashions. A good example is the “Gangnam Style” song created by a Korean rapper in 2012. It flared up rapidly, then subsided, as these fads do. However, we can use “Google Trends” to obtain quantitative data on how the meme grew and then faded. Here are the results.

It is a typical pattern: these curves are the core of memetics. You often see this “bell-shaped” curve because information is, ultimately, a form of energy, and you study how energy moves inside a system using mathematical models. When you study biological systems, you speak of the “Lotka-Volterra” model. When you study economic systems, you speak of the “Hubbert Model.” When you study epidemics, you speak of the “SIR” (susceptible, infected, recovered) model. In their simplest forms, these models are all the same and use the same set of equations. You can read how these equations can be used in meme propagation in a 2018 paper that I published with my colleagues Ilaria Perissi and Sara Falsini.

The model is sufficiently simple that it can be described in words without the need to look at the actual equations. The infection (memetic or genetic; it is the same in mathematical terms) grows proportionally to two factors that multiply each other: the number of people who are not yet infected (“susceptible”) and the number of infected ones (“infective”). In system dynamics, you call this phenomenon “positive” or “enhancing” feedback. The more the system has grown, the faster it keeps growing. Growth may be explosive during the initial stages of the infection, so fast as to resemble an exponential curve.

But, of course, nothing can grow forever. There cannot be more infected people than the total population. Then, people can recover from memetic infections, just as from biological ones. At that point, they are “immune” to the meme or to the pathogen. The key point of the story is that the more immune people there are, the less likely it is that a susceptible person will encounter an infective one. This is called “damping” or “negative” feedback in system dynamics.

A sufficient number of immune people generates “herd immunity,” a condition where the epidemic doesn’t grow anymore but declines. Herd immunity is a concept that was much vilified during the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is a staple idea in immunology, just as in memetics. So, here is how the “Gangnam” meme can be described using the model:

Stop for a moment and consider the implications of these concepts. This model tells us that a meme's growth and decline are different phenomena. Growth is collective; decline is individual. MacKay caught this concept in his “Extraordinary Popular Delusions,” (1841) when he said,

“Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, and one by one.”

Exactly that! Mackay was a great innovator, although he had never heard of memes and memetics. A meme starts to decline when individuals look at the official narrative while scratching their heads.

MacKay was referring to witch-hunting during the 15th-16th century in Europe. Maybe many people had believed in the story of witches at the beginning, but at a certain moment, they started thinking, “Is it really possible that there are women who have sex with devils?” These individuals “recover their senses” and suddenly realize they have been conned. Note the different propagation mechanisms: it is a classic example of an asymmetric fight. Meme propagation by infection is akin to setting a town on fire by carpet bombing. Meme stopping by immunization is akin to guerrilla tactics.

So, the reason Facebook could collapse and disappear is that individuals will “recover their senses,” understand that they are being conned by a system that uses them as cash cows and insults them in various ways, and start leaving. The last one turns off the light, and it is the end of the monstrous machine.

It could happen, but it is more complicated than that. Take a look again at the curve showing the demise of Friendster at the beginning of this post. It has a different shape than the “Gangnam” curve. It doesn’t slow down gradually; the demise of Friendster was a true collapse. It shows the typical “Seneca Curve.” (growth is slow, but decline is rapid).

Why this shape? The model can generate it by adding an equation that includes another “damping” term. But it is a behavior that can be described in words simply by noting how Friendster’s users were not isolated — they communicated with each other and influenced each other. So, when someone left the platform, others would follow their example (*). The result is another enhancing feedback that rapidly brings the curve down; it is a very general phenomenon.

Can that happen to Facebook, that is, falling into the Seneca Cliff? I think it is perfectly possible, and I already saw the mechanism starting to crank up. Several people I know told me they left Facebook, and others tell me they will do that soon. The universe moves according to these cycles of growth and decline, and surely nothing can avoid following the universe’s patterns. Seneca, as a Stoic philosopher, understood that very well.

(*) Note how different this memetic situation is from a typical genetic one. When we have a viral or bacterial infection, if we are immune, we cannot heal other people by being healthy ourselves. It is only their immune system that will eventually heal them. But you can, at least in part, with a memetic infection.

Thank you, Ugo, for the clear explanation of the links between mimetics and FB/social media. I would add this dynamic:: for a great many people, their selfhood and identity is now dependent on their social media presence. Stripped of a social media presence and "likes" (positive feedback that yes, I exist and am worthy of attention), an important source of their sense of self and identity is lost. Once deplatformed, involuntarily or voluntarily, they are shipped to what I call "digital Siberia." Those few of us with independent web presences (blogs, vlogs, etc.) that are not platform-dependent have the equivalent of a ham radio in our attic: a few people might receive our weak signals. Those without truly stand-alone digital "selfhoods / identities" have no backup and so their sense of loss in being deplatformed may be profound. I started thinking about these topics some years ago, for example in this post from February 2011: 800 Million Channels of Me https://www.oftwominds.com/blogfeb11/800-million-channels-of-me2-11.html

Following this line of thinking, perhaps FB et al. won't collapse until there is a non-profit-maximizing platform they can use, the equivalent of a public utility that is managed transparently and that treats every user the same. Thank you for all you do-- warm regards, Charles Hugh Smith https://charleshughsmith.substack.com/

I appreciate your explanations and illustrations. What prompted me to leave, and this was many years ago (with an account under another name), was that FB fiddled around with the algorithms such that I couldn't be sure if my posts were reaching my followers. So I switched back to using email and a newsletter. As for my personal friends and family interacting with me on FB, I figured my leaving FB would be a useful test of the relationship. It was.