Kill the King, Win the Game. The World as a Chessboard

The Dawn of a New Strategic Era

Saddam, Qaddafi, Assad, Maduro…. Who’s next? Maybe someone named Donald?

The last Sasanian King, Yazdegerd III, reigned from 632 to 651. He was killed, it is said, by a miller while running away, nearly alone, from the invading Arab armies. With him went the Sasanian Empire, forever lost in the mists of history.

The game of chess existed in Iran at the time of Yazdegerd III, but it was a novelty. So, we may imagine his death inspired the rule that gives a player victory when the enemy king is dead. In Persian, it is Shah Mat (شاه مات), “The King is Dead,” a term that has arrived to us as “Check Mate.”

It is difficult to be a king: you claim to have power over your subjects, but you yourself are always at risk. Another, more powerful king may checkmate you at any time. It is the destiny of Kings and rulers, no matter on which source they claim their power to come: a democratic vote, or a divine fiat. One moment you are at the top, the other you are at the bottom. And another king takes your place.

The list is long. Modern examples include Saddam Hussein, Muammar Gaddafi, Bashar al-Assad, and just a few days ago, Nicolás Maduro. A case that looks eerily similar to that of Maduro is how, in 1939, Benito Mussolini ousted King Zog I of Albania in a nearly bloodless coup, turning the country into an Italian protectorate. Zog spent the rest of his life in France and died in April 1961. Mussolini preceded him to the Elysian Fields, hanged upside down in Milano just six years after his apparent Albanian triumph.

It is nothing special in history. It would be special if, somehow, God or democracy actually made a king invulnerable and imperishable. But it is not the case. It has been said that Trump behaves like a Mafioso, a Mafia boss. In many ways, it is true. His latest stunt in Venezuela looks like a textbook example of a clash of mafia bosses. I don’t pretend to be an expert, but my origins are from Southern Italy and I have a certain experience with how these things go. Mafia and the many similar organizations (Yakuza, Camorra, 'Ndrangheta, Bratva, etc.) are microcosms showing how a state works. They operate mostly by intimidation, rarely by actual violence.

The scarcely glorious end of Nicolas Maduro illustrates an interesting evolution in the Western Empire during the past few decades. Not anymore mass exterminations, but Chess-style strategy: kill the king, win the game. We may be sorry for the destruction of what was once called “international rules,” but, in many respects, it is a positive development. After all, Mafia rarely engages in mass exterminations, unlike states.

I examined the human tendency in terms of mass killing in my book “Exterminations.” We can trace the modern genocidal trends to the work of Giulio Douhet (1869 – 1930), one of the most evil minds in human history. In his book Il Dominio dell’Aria (1921) (The Command of the Air), he theorized war as a sort of rat extermination job. Conventional armies were obsolete, he said. All that was needed to do was to launch fleets of bombers directly against enemy cities to exterminate civilians, something that could be done methodically, as a sort of wall painting job. At some point, the survivors in the bombed country would have had no choice but come to terms with the government of the attacking country (it is typical of military strategists to neglect the idea that the enemy could respond in kind). Douhet maintained that his proposal would lead to a quick resolution of conflicts, involving a smaller number of casualties than a conventional, protracted war. In a sense, he was the inventor of the concept of “humanitarian bombs,” even though he never used that term.

We don’t have to fault Douhet for the waves of extermination that swept the world after the publication of his book. He simply gave an explicit form to ideas that were being enthusiastically adopted at the time. The idea that you could obtain victory in a relatively cheap manner by carpet bombing was irresistible to politicians and generals in the same way. Of course, that implied considering the enemy population as little more than rats, but, hey, that’s just a detail, isn’t it?

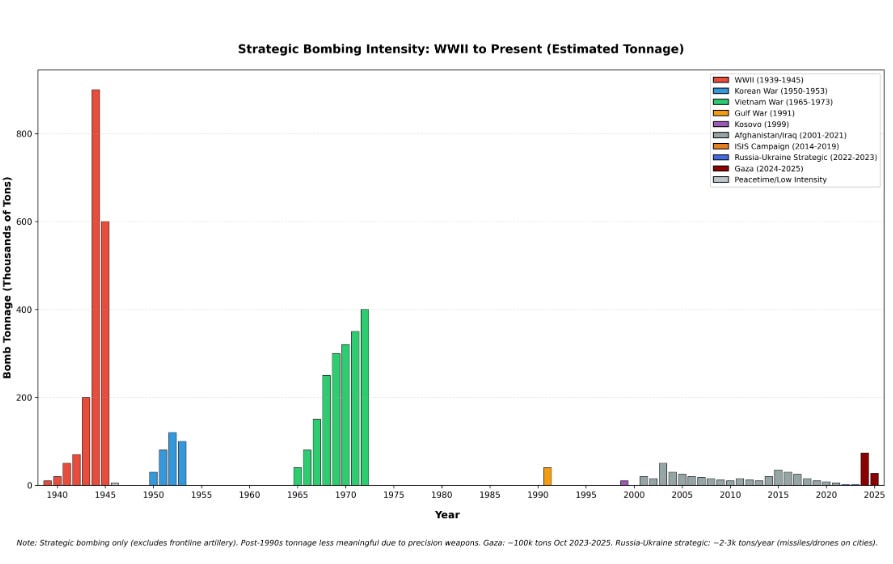

Terror bombing against civilians predates Douhet, and it was already tried during World War I, mostly unsuccessfully because the technology was not mature enough. Then, it grew exponentially with WWII. Here is the trend (graph prepared by Claude Sonnet 4.5.)

Note a few things in this graph. First, it reports only strategic bombing, that is, bombing directed at the enemy territory, far from the frontline. This kind of bombing may be theoretically aimed at military infrastructure but, in practice, it hits civilians as well. During WWII, Allied bombing was directly and specifically directed at the civilian population of the Axis countries. Note also that practically all the bombing in the graph was generated by Western States. Russia, China, and other Non-Western states contributed essentially zero to the graph. Even in the recent war in Ukraine, the bars are nearly invisible: most of the bombing by both sides was directed at military targets near or close to the frontline, not at the extermination of civilians. Incidentally, the recent Ukrainian attack against Vladimir Putin’s residence looks correlated to the Venezuelan coup against Maduro. If it had succeeded, it would have been a double triumph for the West. The fact that it failed may indicate that it was sabotaged from the inside, but we will never know for sure.

So, how do we interpret this set of data? Overall, apart from the horrific exception of Gaza, we see a trend toward lower intensity and better-focused bombing. In Syria and Venezuela, regime change didn’t require the extensive bombing that had been directed, for instance, at Iraq at the time of Saddam Hussein. In both cases, the change was obtained by decapitation strikes that didn’t even involve the murder of the local leader. In Iran, there were several strikes directed at the elimination of some political and religious leaders. In part, they were successful, although regime change was not obtained, at least so far.

It is a fundamental change of strategy. For the reasons of this trend, there are several possible explanations. The simplest one is that carpet bombing directed against civilians always was a bad idea, even in purely military terms; it just doesn’t work the way Douhet had proposed it. The experience of WWII should have made that clear. In politics, however, everything is subjected to the “Eastern Island Syndrome.” That is, if things are bad, it is because we didn’t build enough statues. We need to build more, and surely things will improve. Just change “bombs” for “statues” and the story is the same.

In practice, bad ideas follow a memetic cycle in the human collective consciousness, and mistakes tend to be repeated over and over, at least until the generation that made them first disappears. The cycle of Douhet’s ideas seems to have exhausted itself in about 50-100 years. There remains the exception of the Gaza bombing, but that’s not what Douhet had in mind.

There are other possible interpretations of the current strategic trends; one is that the huge bomber fleets that were available during the 20th century do not exist anymore. They are simply too expensive and too vulnerable to surface-to-air missiles. In any case, though, the latest developments may not be so bad. At least, we got rid of a set of horrible ideas, such as that it was a good thing to kill people in order to “bring them democracy” (as it was said about Iraq) or that bombs could be “humanitarian” (as it was said about Serbia). If political changes are obtained by the decapitation of leaders (in whatever sense you want to understand the term), it is much better than by killing huge numbers of innocent people, as it has been fashionable to think and do in the West up to recent times.

There are many ways in which the new tendency of winning the game by killing the king could backfire. If the king doesn’t die, he may strike back as in a failed gambit in Chess. Things change rapidly: so far, most wars were fought in order to find land for a country’s people, and leaders thought that the problem could be solved by aerial bombing. In the near future, the global depopulation trend may turn the problem into the opposite: finding people for a country’s land. That I discuss in my upcoming book, “The End of Population Growth,” soon to be published. As always, we keep marching toward the future without really understanding what we are doing.

Quote

As always, we keep marching toward the future without really understanding what we are doing.

Unquote

Love that

First country were these tactics were used is often forgotten - Serbia. Its especially strange because Serbia is, at least geographicaly, European country. It was much more difficult to remove President Milošević. Both bombing and regime change tactics were first used in Serbia. Even in your post there is no mention about Serbia and Serbia is not very far from Italy.