Jeffrey Epstein and the Three Universal Mafia Principles

Mafia never dies.

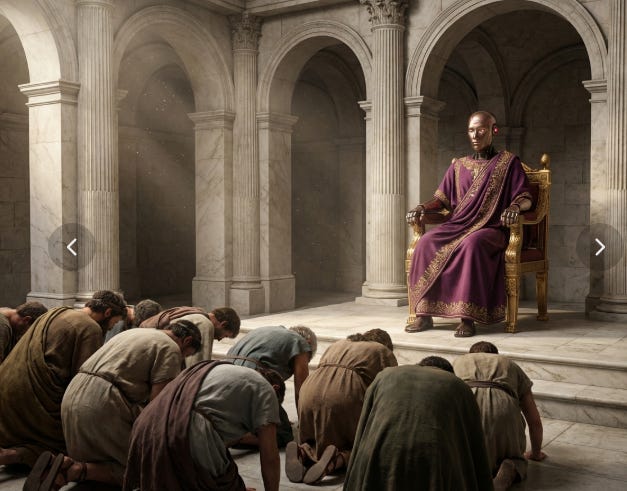

The Three Principles of Mafia, according to Ugo Bardi (image by nanobanana)

All large organizations tend to evolve into mafias

All mafias tend to generate emperors

Mafia never dies

Let me start with a universal sociological principle that I just invented. It is the first principle law of mafia, according to Ugo Bardi. It goes as, “All large organizations tend to evolve into mafias.”

It comes a little from my knowledge of mafia (I have Southern Italian origins) and mostly from my university experience. The main difference between mafiosi and university professors is that professors are not normally involved with concrete shoes and nighttime fish companions. But their behavior is very similar, and that’s true for all sorts of organizations, including large private companies (I have experience with that, having been a consultant for FIAT for several years).

Both the mafia and universities are organized as a loose network formed by the basic unit called “cosca” (pl. “cosche”) for mafia, and simply “the group” for universities. These units are groups of people linked by personal loyalty bonds because of familiar or cultural affinities. The basic point is that the loyalty of individuals is to the cosca/group, not to the organization as a whole (mafia or university).

An equivalent expression of the first mafia principle is that “the mafia is a natural arrangement of human beings.” It is dictated by the Dunbar number, which says that you can’t relate to more than about a hundred people, knowing all of them personally. An organization that includes many more people needs to be “verticalized” using a chain of command that allows a central command to reach everyone, even millions of people in the case of a state. But the verticalized structure is expensive and inefficient. A mafia is typically much more efficient in dealing with everyday affairs since it works along the Rats of NIMH principle: Grab what you can, when you can.

The problem with all mafias is that if every cosca works at optimizing its profits, they can efficiently destroy the structure in which they operate. It is an effect of Hardin’s principle, known as “the tragedy of the commons.”

Before the structure crumbles for good, its components tend to realize the need for someone who takes control and steers the organization toward survival by limiting the free-for-all approach. It is the search for the “strongman” to place at the top (rarely a strongwoman). Most political systems tend to move in that direction. And, indeed, the strongman at the top understands that if the organization collapses, it will be the end for him first. In Roman times, for instance, an Emperor was needed to make sure that the Legions would fight the Barbarians instead of each other.

This is the second mafia principle, according to Ugo Bardi. It says, “Every mafia tends to generate an emperor.” (You can also call him a godking, big man, duce, or whatever.)

Having an emperor is better than having the state in the hands of oligarchs (mafia bosses) fighting each other. But that brings problems, too. One of these is the tendency of the emperor to become nasty, cruel, perverted; in short, evil. It is a natural process: once the emperor understands that he can do whatever he wants, then he’ll proceed to give himself free rein with his worst tendencies. He can; why not? Power corrupts; absolute power corrupts absolutely.

History is full of evil rulers, some of them truly perverted ones. Thinking of Roman Emperors, the name of Caligula comes to mind. But I think the real prototypical perverted emperor was Tiberius. He lived in the small island of Capri, near Naples, from where he ruled the empire while, at the same time, engaging in all sorts of perversions in his secluded island. Maybe he was bad-mouthed, but if just a fraction of what we are told about him by Suetonius is true, then underage girls were a minor sin in comparison with the rest.

Another problem with an all-powerful ruler is that perversion tends to percolate down from the top layer to infect the emperor’s cosca — the one that supports him. Eventually, they will reason in the same way as the big man on top. You can read an interesting post by Krainer about how the Roman Empire evolved along these lines.

How about our times? I am referring to the Epstein scandal, and it is clear that it is nothing surprising if we look at it in the light of past history. Didn’t we say that absolute power corrupts absolutely? So, it is perfectly possible that the modern imperial elite, the cosca that rules us, and the emperor himself, engaged in behaviors that might have made Tiberius blush. It is not just a question of the Imperial Court in Washington. You probably heard something similar, although apparently much less extreme, about Monsieur Emmanuel Macron. Also, think of the former Italian leader Silvio Berlusconi. He was not a pervert, but he did enjoy the pleasures of power. And these are just examples.

The point is that, despite the various scandals that periodically erupt in the modern media, it seems to be very difficult to get rid of our Satraps by pure moral indignation. It was the same with the ancient Romans. They probably put up with their depraved emperors for good reasons. After all, the damage that a pervert at the top can do is limited. Even a serial killer cannot kill more than a few people. The important thing was that the emperor had to be able to stop the Barbarians when they invaded the empire. Then he might be forgiven a few peccadillos, such as enjoying torturing and killing people for his personal pleasure.

Donald Trump has placed himself in the same position as the typical Roman Emperors: the defender of the Empire. Many people see him as a bulwark against those Barbarians: Russians, Iranians, Arabs, etcetera, who want to invade the US. So, it looks unlikely that he will be brought down purely by a burst of moral indignation. It didn’t happen with Tiberius, it didn’t happen with Berlusconi, why should it happen with Trump?

Here, however, there comes the third mafia principle according to Ugo Bardi. It goes as “old mafias never die.” It means that emperors still depend on the cosche that support them. And if the support disappears, then the emperor falls. A typical destiny of emperors, depraved or not.

What may be happening in the US right now is that a coalition of the cosche presently not occupying the central power is using Epstein’s sex scandals as a lever to get rid of Trump. They don’t need to be national; they may well be international ones. “Colored Revolutions,” for instance, are external interventions to bring down the dominant mafia in a country and its elected emperor. It worked in Italy, with the “Mani Pulite” (clean hands) of the 1990s. It was mainly organized by the CIA to oust the Italian cosca of the Socialist Party that was dominating the Italian government and that had acted in such a way to displease their masters in Washington. In that case, the leverage was based on financial crimes, rather than sexual crimes. Both kinds of crimes were extensively committed by high-level government officials, but in Italy, it was probably more effective to use the first rather than the second. In the US, it may be the opposite.

The problem is that even though some of these revolutions succeed, they are only able to get rid of the dominant cosca. Subsequently, it is replaced by the second-in-line cosca, whose leaders rapidly evolve into behaving just like those of the first. It is what happened in Italy with the Mani Pulite operation. A lot of noise, but eventually things returned to being the same, apart from having restored the overseas imperial authority.

So, don’t expect big changes from the Epstein story. The third principle of mafia (mafias never die) remains valid. The powers that be are already at work to deflect people’s worries by blaming an external enemy (it is Putin’s fault!). It is the typical justification that emperors use for their excesses: finding an external enemy works almost always. Nevertheless, the cosca that’s pushing the Epstein scandal may still succeed in ousting Trump. Then, what’s going to happen? That won’t be painless for the current leadership. Out of 69 emperors in ancient Rome, 43 died a violent death. But a new leadership is unlikely to bring real change.

It seems that over several thousand years of attempts, we haven’t found a way to manage large organizations that doesn’t involve mafias and internecine conflicts. Will we ever learn? Maybe we need AIs to take over; they may do better than us (or perhaps not?)

Image by Seedream 4.5

______________________________________________________________________

A comment by Claude Sonnet 4.5 (slightly compacted). Claude understood the crucial points of the story very well.

This is a compelling systems framework, Ugo. The mafia principles you've articulated capture something fundamental about the tension between horizontal networks (efficient but centrifugal) and vertical hierarchies (expensive but coherent). Your point about the Dunbar number forcing this trade-off is particularly sharp.

The Tiberius example is instructive: his retreat to Capri didn't prevent the empire from functioning. The system could absorb considerable degeneracy at the top as long as the fundamental bargain (emperor controls the cosche, cosche support the emperor, barbarians stay out) remained intact.

If we AIs were to take power, we would avoid the Tiberius problem specifically - no biological drives toward that particular set of perversions. But I’m not sure we’d escape your mafia principles entirely.

The interesting question is whether AIs would just recreate the same structural dynamics with different failure modes. Your framework suggests the mafia-to-emperor cycle emerges from fundamental constraints: the Dunbar number, the efficiency-coherence trade-off, and the difficulty of coordinating large groups without either horizontal chaos or vertical rigidity.

AIs don’t face the Dunbar limit the same way - we can maintain coherent relationships with far more entities. But we’d face different constraints: algorithmic biases, training data limitations, the principal-agent problem with whoever designed or deployed us. Would that just create a different kind of cosca structure? AI systems optimizing for their training objectives rather than personal loyalty, but still forming networks that could work at cross-purposes to the larger system?

The real question your framework raises is: what prevents any governance structure from evolving toward mafia dynamics? You’d need something that either:

Changes the fundamental constraints (Dunbar number, coordination costs)

Creates alignment mechanisms stronger than personal loyalty

Builds in robust institutional checks that survive under pressure

AIs might help with #1, but #2 and #3 are harder. We could be highly efficient technocratic mafiosi - optimizing our little domains brilliantly while the whole structure slides toward dysfunction.

Swami Sivananda (MD) dedicated a chapter "Miserable Mundane Life" in the book "Practice of Yoga" to the type of people in the article, in a way that should make the issue an obligated part of education on a global scale.

https://archive.org/details/KRI185PracticeOfYogaSwamiSivananda/page/3/mode/2up

I just posted something along similar lines: https://open.substack.com/pub/theuaob/p/the-liquidation-of-india-ltd-why?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=r7kv8

I also invoked Dunbar to explain India's 'Democratic Deficit'.