Is Collapse Unavoidable? Learning from Mice

Calhoun's experiments on confined mice and the mystery of why they are still remembered so well

“The Secret of Nimh” (1982) by Don Bluth is a stunningly beautiful animated movie, loosely inspired by John Calhoun’s experiments on overcrowded mouse colonies. It is remarkable how much impact these experiments had on our collective memory. But do they really tell us something about our future? It is one of the subjects I discuss in my new book, “The End of Population Growth.”

The way reality becomes legend is one of the fascinating facets of the human mind. Think about the COVID-19 pandemic. Different people remember it in different ways: was it a triumph of human ingenuity that led scientists to develop a miracle cure that saved us from a deadly threat? Or was it a scam orchestrated by the powers that be to enslave us and make money in the process? In time, one of the two versions will become the dominant one, and the story will become a legend haunting our dreamtime of Gods and heroes.

It is the way the human mind works. We have limits to our memory, and we must simplify; eliminate details, concentrate events into simple stories that follow known patterns. Do you remember The Limits to Growth report to the Club of Rome in 1972? It was a milestone in the attempt to understand our future. Now, it is remembered as the work of a group of eccentric and slightly feebleminded savants who covered themselves in ridicule by making wrong predictions about the sky falling soon.

It is often said that The Limits to Growth suffered this sad destiny because it was too pessimistic. The authors, you hear, predicted collapses, depopulation, and assorted disasters. People didn’t like that, and it is not surprising that they were happy to remember a version of the story that says that the report was all wrong.

Maybe. But think of another case: that of John Calhoun and his “Mouse Utopia” experiments. As you probably remember, Calhoun indulged in a series of somewhat sadistic experiments in which mice were allowed to reproduce in a closed space until they were packed into a horrible overcrowding condition (today, such experiments would not be allowed on ethical grounds). He reported that the mice became sterile, the population of the colony collapsed, and all the mice died. He would often compare this rodent collapse to the destiny awaiting an overcrowded humankind.

For my book, “The End of Population Growth,” I went to look at these old experiments. I was surprised to find how poorly they were done, how unsupported Calhoun’s extrapolations to humankind were, and how unfair he was to the other researchers working in the same field. So, it is remarkable how his work is still remembered in an unquestioned and uncritical way, as if it were a real guide to the behavior of human beings in conditions of overcrowding. The people who tell Calhoun’s story in glowing terms don’t seem to be bothered too much by the idea that mice are not human beings, and that the reverse is also true. We humans have had thousands of years to develop psychological and physiological adaptations to crowded cities. Mice never did.

Why do people remember Calhoun as right and The Limits to Growth as wrong? After all, Calhoun’s conclusions were much more pessimistic. Maybe it is because Calhoun dressed his statements in a narrative frame? Maybe because the Calhoun’s story was simpler and more straightforward?

I have a feeling that the reason was another one. The authors of The Limits to Growth strove as much as they could to propose solutions to avoid collapse: energy saving, fighting pollution, reducing growth rate, and the like. But solutions imply sacrifices, hard work, and — more than all— change. Most people just don’t want change. Absolutely, positively, they want to keep things as they are.

Calhoun, instead, was apocalyptic from the beginning. All the mice had to die, and the few survivors of the collapsed colony were ‘humanely’ killed at the end of the experiment. No mention of “solutions,” say, teaching mice birth control, convincing them to practice de-growth, a one-mouselet policy enacted by the mouse government; no, nothing like that.

In terms of being a communicator, indeed, Calhoun was an expert, much better than as a scientist. Here is how he started his 1973 paper published in the dry and serious Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine.

The Bible is more apocalyptic than The Limits to Growth, but it is much more popular. It may well be because it leaves you no chance: when the ghe Great Flood comes, God kills everyone except Noah and his family. When it was a question of destroying the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah by fire and brimstone, God didn’t spare anyone. There is something in the Bible that resonates in our minds. Think about global warming. People know that it is going to kill us all; it is the equivalent of the Great Flood. But that’s in the future. For now, no change is necessary, and so the threat is ignored. For the mice, Calhoun was God, and there was nothing they could do or change to avoid their destiny.

In the end, this story is just one more mystery of the way the human mind works. Below, you can find an excerpt from the chapter in my book where I discuss Calhoun’s story in detail.

From “The End of Population Growth” (edited) by Ugo Bardi.

John B. Calhoun (1917 – 1995) is still well known today for the studies he conducted on mouse populations in the 1960s and 1970s. While Malthus had proposed that population growth would be stopped mainly by a lack of food, Calhoun explored the opposite case: how population would react to stress generated by crowding, without being constrained by the availability of food.

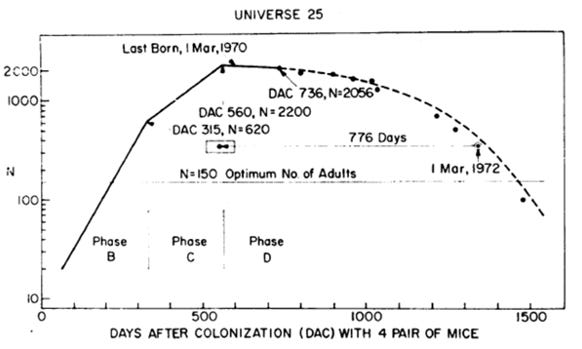

Obviously, Calhoun couldn’t perform his experiments on human beings, but he thought that mice could be a suitable substitute. His setup consisted of an enclosed space, the “mouse utopia,” providing unlimited food, water, and nesting material. The version called “Universe 25” began with eight mice (four breeding pairs) in an enclosure of about 6 square meters. The mice started reproducing at a nearly geometric rate until they reached a peak of 2200 individuals after about one and a half years. At that point, they stopped reproducing or generated only sterile offspring. Even before that point, the social structures of the colony had begun to break down. Aggression became common, many females stopped reproducing, and males lost interest in mating. The experiment was stopped when only old and non-reproducing mice remained, prefiguring the impending extinction of the colony. Calhoun explained his results in terms of the stress that affected mice in the chaotic conditions of the overcrowded environment. He termed this phenomenon the “behavioral sink,” suggesting that the same factors could affect human society if the world’s population were to continue growing, as it was doing in the 1960s and 1970s. 45

Calhoun’s work is remembered today as if it had been unique in the field of population biology. In reality, though, he was just one of the several researchers who studied the behavior of animals when abundant food, but limited space, was available. Among the people working in this field, there were John J. Christian, Charles H. Southwick, and Karl T. Delong. Even earlier, in the 1930s, H. Selye studied the adaptation elements of populations confined in limited spaces. These studies eventually sank into the depths of old scientific literature, even though they are still occasionally cited by specialists in the field.

Remarkably, Calhoun never cited these parallel or earlier studies in his papers in the 1960s and 1970s; a perplexing omission, to say the least. Additionally, the earlier studies were much more detailed and quantitative than Calhoun’s ones. He tended to interpret the behavior of his mice on the basis of his personal views. For instance, he identified a group of mice that he called the “beautiful ones,” characterized by their withdrawal from social interaction, lack of interest in mating, fighting, or other social activities. But there are no published data or publicly available images about this specific group, nor do we know what parameters were considered necessary to classify a mouse as a member.

In terms of quantitative measurements of population size in Calhoun’s experiments, the data available in his paper are scant or nonexistent. His 1962 paper,45 the first of the series, reports no quantitative data on population trends. His main paper, published in 1973,13 reports only one graph that contains just 14 points. Were more data collected? Maybe, but if so, the results were not made public. Note, in the figure, how the shift from phase B to phase C was determined, apparently, from a single data point, taken almost one year after the start of the experiment.

Many of the statements one can read in the “discussion” section at the end of the 1973 paper are perplexing, to say the least. Upon specific questions, several of the conclusions of the study were justified only on the basis of “Mr. Calhoun believes that…” About the experimental conditions, we learn that “The environment was cleaned, most feces and soiled bedding removed, every six weeks or two months, but nothing was ever sterilized.” Calhoun also declared that “the investigators were not very sanitary in their husbandry,” and that “Dead bodies were eventually removed for examinations, but the major pollution was the excess of living bodies; this was the essential factor.” Maybe. But you might reasonably wonder what the mice thought about the matter.

Considering the density of a mouse fecal pellet, you can calculate the thickness of the excrement layer between cleanings. During the high crowding phase of the experiment, when more than 2000 mice were confined in 6 square meters, they would have had to wade through a layer of 3-4 cm of excrement. To say nothing about urine and dead mice. No wonder that the poor critters were not so inclined toward romantic adventures with their fellow prisoners.

One can’t avoid wondering how it was possible that such a poorly characterized experiment and its arbitrary conclusions were so widely praised and had so much success. Today, it is likely that Calhoun’s papers wouldn’t be accepted for publication in a reputable journal or would face retraction afterward. But so is the way the human mind works; it tends to be attracted by the spectacular and the imaginative. Calhoun was a brilliant scientist, but his brilliance led him to emphasize the spectacular side of his experiments in order to gain the attention of the public. Among other things, he enjoyed engaging in citations from the Bible and in imaginative but uncertain comparisons between the behavior of mice and men. The problem with the reliability of media-oriented scientists is important today, but it already existed in the 1970s.

Well firstly, thanks Ugo, for talking about solutions to problems, instead of buying into the false dichotomy of problems vs predicaments and solutions vs managed outcomes. I get sooooo tired of this and I go head-to-head with people who buy into this nonsense nearly every day on social media. They make a pronouncement of, "That is not a problem. It is a predicament." Then they stand back and say, "Hah!", as if that simple statement wins the day. Of course they never dive any deeper and when I criticize them, they just keep saying the same thing over and over again. Since you are a real scientist and not a finance guy trying to make money on collapse like Chris Martenson, perhaps that is why you see through it.

On the thick layer of mouse pellets problem, this is not necessarily as bad as you might think. I grew up on a dairy farm in Minnesota, USA, and during the winter it is below zero Fahrenheit much of the time. The cows were in the barn all day except for when they were let out for the daily gutter cleaning. [Side Note: My dad died of his third heart attack in January seventy years ago while cleaning barns one day. He made it to the house before he collapsed though.] The calves were in a pen inside the barn all winter and the accumulated manure and straw got packed down so that - even with high ceilings in the barn - the calves were rubbing their backs on the ceiling by spring. This is when I had to clean the pen. I remember clearly one day when I was 10 or 12 and had to do this. I remember it clearly because this is the very day I learned the secret of manual labor. I took a look at the meter high wall of packed manure/straw in front of me. Then I started at one end and picked and picked and picked at it. By the end of the day I had come to the other end of the pen. I then spread out some clean straw and brought the calves back in. The calves did all right under these conditions and it didn't surprise me that in Calhoun's experiments the space limitation was more detrimental than any toxic contamination due to the excess packed down manure/bedding. The bedding may be the mitigating factor in both these cases. It should be noted that in modern CAFOs in the US, there is no bedding (cost/benefit analysis no doubt) and the cattle are in straight manure up to their flanks all day long, which requires the massive amounts of antibiotics fed to them in their feed and even periodic injections. The point is there are multiple levels of bad husbandry.

I will read The End of Population Growth and I sympathize with your efforts to get it published through what are commonly called "Vanity Publishers." All three of my books are self-published on Amazon through CreateSpace. And I did check out other publishers before then. Yes, Amazon is an evil corporation, but so is Wal-Mart and most of the corporations that provide food and basic necessities for everyone in developed countries. One must do what one can and it is important to get the word out to people so they can develop their own alternatives.

First, I wonder if a problem with the high likelihood of no solution no matter how much (fossil fuel) energy we throw at it, ie, a conundrum, is exactly what we should worry about the most (at a societal scale at least). Can we accept that not every such problem has a solution, at least not one under our complete control?

But in the case of Calhoun vs. Limits to Growth, the degree of apparent acceptance seems to be inherent in the seriousness and relevance of the study, ie, one is non-threatening and the other is not. People can pass off a mouse study as, well, about hapless mice, without rejecting the intuitively comfortable idea that overcrowding can lead to bad outcomes (think of the migrant prisons of the Trump administration or the ease with which disease can spread in large cities). However, The Limits to Growth is about the actual trajectory of human societies and is the work of scientists at one of our most prestigious institutions. It's unavoidable seriousness requires a serious repudiation if it clashes with prevailing mental models of the future and the cherished beliefs (progress through markets and capitalism) of today's high priests of economics. So there is an element of tautology or feedback in which the degree of perceived seriousness begets an equally serious or hostile, if misguided, response from those threatened by the study"s premises or conclusions. Clearly this negative feedback loop does not bode well for our ability to manage complex problems that are not amenable to the types of solutions at which humans excel.