Fahrenheit-451: Is it is Becoming Reality?

E-books and Printing on Demand are Good Things, but they have a Problem.

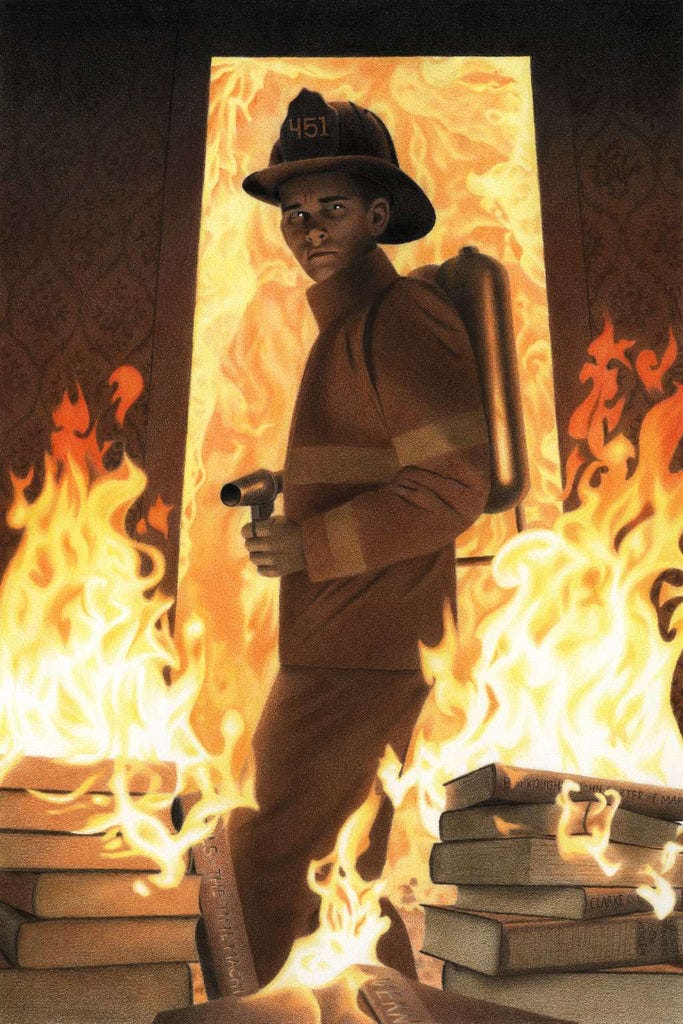

“Fahrenheit 451” was a dystopian science fiction novel written by Ray Bradbury and published in 1953. It told the story of an oppressive government that had decided to destroy the past by burning all the books in the world. Only a group of enlightened “Book People” maintain the ancient knowledge by memorizing the old books in their heads. It was a remarkably prescient story for many reasons, one that most people in the story seemed to find wholly natural and perfectly correct that books had to be burned.

Years ago, once a book was printed, “Pilate’s Law” was the rule (“What I have written, I have written”). Corrections to the printed text were simply impossible. No more, now that books exist mainly as e-books or are printed on demand.

After I published my new book, “Exterminations,” a few days ago, I discovered that the text contained a weird mistake. When describing how the British government had initially set up “Soup Kitchens” for the starving Irish during the great famine, the text said “Soup Chickens.” (1). With the miracle of printing on demand, I could fix it in about half an hour for both the printed and the e-book versions. I apologize to those who already bought a printed copy of the book, but maybe it will become a collector’s item!

But, with this freedom of changing the text, there come also problems. Books are no longer fixed and immutable, as the Ozymandias inscription was set in stone. That opens up all kinds of possible scams and disasters. What if I insert an event that just happened in a book I published some years ago, and then I claim I am a prophet? What if someone copies my text, inserts it in a book that he had published earlier, and then claims I infringed his copyright? Imagine I were to receive a phone call from someone who suavely tells me, “Mr. Bardi, you have been disparaging my client’s products in your book and he is not happy about that (2). So, I would suggest that you remove those statements from your text. We would hate it if something bad happened to your grandchildren when they come home from school.” What if someone who doesn’t like my book just makes it disappear or demotes it to such a low level in the search engines that nobody can find it anymore? (it happened to me with my “Seneca” blog when it was on the Google blogger platform).

All these possibilities are soft versions of Ray Bradbury’s novel Fahrenheit 451. That novel was published in 1953, and at that time, the author could only think the government could get rid of books they didn’t like by burning them. Today, it can be done much more easily simply by the command “delete,” and books disappear forever.

These problems could be solved if publishers adopted the same practice that ArXiv, a scientific paper repository, adopts. On ArXiv, you can change your text as you like, but the old copies remain online and are always accessible. So, everyone can see whether you just fixed a typo or two, or you made some important changes out of shame for having published an idiocy, or because someone threatened you with a shotgun. It is a concept similar to that of “blockchain.”

That may happen in the future, but there remains the general problem that the Internet looks like someone suffering from a mild form of Alzheimer’s. It tends to forget things and, worse, to remember them wrong. The Powers that Be do their best to make what they think is inconvenient for them disappear from the Web, and they often succeed. Gallant efforts to keep a record of everything are done with the Wayback Machine, but they are continuously under attack by hackers and, probably, evil forces at much higher levels.

So, will humankind’s memory fade out like that of an Alzheimer’s patient? Is Bradbury’s dystopic future becoming real? I think it may well happen. So, I keep printed copies of the books I read. They won’t last as long as Ozymandias’ inscription, but longer than a web page that can be erased in an instant. I suggest you do the same. We have not yet arrived at the point in Bradbury’s novel when people had to keep old literature alive by memorizing it in their heads, but we may be moving in that direction.

________________________________________________________________

(1) This sounds funny, but it is a terribly sad story that I describe in one of the chapters of my book. During the first year of the Great Famine in Ireland, the British government set up “Soup Kitchens,” which saved the lives of hundreds of thousands of Irish people. Then, for some reason, they were dismantled, and millions died. That gives credence to the accusation that the British exploited the famine to get rid of a good number of their unruly Irish subjects.

(2) I said that about Bisphenol-A in “Exterminations.”

Publishers of eBooks can (and do) reach out and change the copies of books already in users' possession, or even unilaterally "take them back." I knew I had read about this being done by Amazon, and a search uncovered the following interesting article describing the legal basis for this at https://www.zdnet.com/article/why-amazon-is-within-its-rights-to-remove-access-to-your-kindle-books/

No one reads the fine print in all these "user agreements" (written in legalese and often dozens of pages long), but their legal right to do this is enshrined in there somewhere. It is annoying that despite not legally owning an eBook, it can often be priced at (or even above!) the price of a printed copy. If for no other reason, this seems wrong, given that the cost of producing an eBook is significantly lower.

In addition for the reasons you offer, I also personally prefer the experience of reading a hard copy to reading an eBook, and will generally go that route unless the price of the eBook is WAY lower. But on those few occasions when I do purchase an eBook, it is easy enough to immediately strip off the DRM and store a copy in a separate file using something like Calibre eBook management software. That way you can protect it from being yanked or edited, and can read it on any device you choose without registering the device with companies who want to "reach out" and fiddle with the content.

Of course, the absence of DRM puts users on the "honor system" with respect to sharing it with others who have not purchased it. And yet many authors trust their readers to do this--I have bought a few that explicitly state they are being provided without DRM. I always appreciate and respect that trust.

Great insight, very concerning though and I wish I hadn’t read this!