Can we Stop the Wave of Violence?

Facing the epidemic of evil, we need to generate herd immunity.

I think the best term to describe how we feel in this moment is “powerless.” We are watching what’s happening, without being able to do or say anything, surrounded by people who are bewildered, or swamped by the propaganda machine, or taking sides as if they were watching a football game, or delving into complicated geopolitical reasonings, as if there were a logic in what’s happening. This is an attempt to use system dynamics concepts to understand what’s happening and to generate herd immunity in order to stop the madness.

Is there an evil mind behind what’s happening? I think not. If you like, you can use the term “emergent phenomenon,” used in physics to describe things that are not hard-wired into the system, but emerge as consequences of its properties. Clouds do not necessarily bring rain, but in some conditions they do. You could say that rain is an emergent property of clouds. In the same way, temperature gradients over the ocean do not necessarily generate hurricanes, but under some conditions, they do. Hurricanes are emergent properties of the interaction of the ocean with the atmosphere. Governments, then, do not necessarily generate wars, but sometimes they do. You could say that wars are an emergent property of the human mind.

The current wave of death and destruction is not the first, and it will not be the last (at least, if someone survives the current one). Maybe the story of witch hunting can help us understand how these evil patterns arise and then subside. I explored thia subject in my book “Exterminations,” finding many similarities with other waves of violence that engulfed and are still engulfing our world.

Nowadays, witch hunting is perceived as the paradigm of evil. Something that we tend to consign to a mythic world of fanaticism and religious folly; an age that was over long ago, and that will never return. But, as always, things are more complex than they seem. Let’s start with some data.

You see how the craze started in the early 1500s, peaked about one century later, and then declined, with the last official witchcraft execution in Europe in 1782. Evil follows a pattern: it grows, peaks, and then subsides. It is a typical pattern of emergent phenomena. But why?

We can understand the pattern if we use the concept of “meme.” The term was coined by Richard Dawkins in analogy with that of gene: Memes are “virtual genes,” ideas that infect people’s minds and that, sometimes, take up a life of their own. They are passed from person to person, and they behave very much in the same way as biological viruses. Daniel Dennett said that human beings are “meme-infested apes,” and that is a good definition of some facets of human behavior.

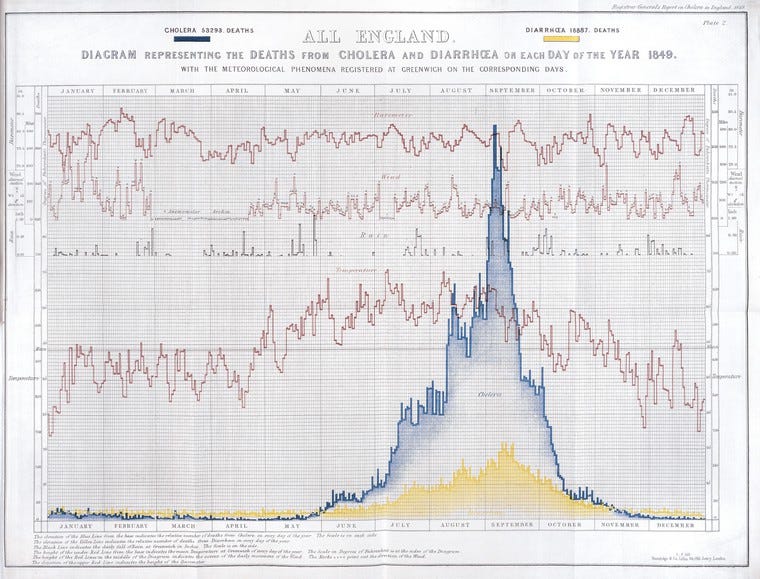

Memes and genes follow similar patterns of growth and decline. You can see here a classic case of this kind of curve in the real world, the cholera epidemic in London of 1849. You can find the equations of the model that generate these curves in my book.

The London bacterial epidemic lasted less than one year. The memetic epidemic of witch hunting in Europe lasted much longer, about two centuries in Europe, but the shape of the curve was the same. In our times, people have been infected with various evil memes, a typical example is that of Iraq being supposed to possess “weapons of mass destruction,” and hence deserving to be destroyed by bombing. The shape of the memetic infection is the same, in this case, seen in terms of the number of mentions of the concept in books, according to Google Ngrams.

The current dominating meme with Iran is basically the same. All these evil memes are similar: someone (witches, terrorists, Muslims, the new Hitler, or whatever) and we must destroy them before they destroy us.

In the list of these historical madnesses, witch hunting is impressive because of its sheer absurdity. How could people really believe that women had sex with the devil? Or that they were flying in the sky riding their brooms? Yet, these were some of the accusations leveled against them and, apparently, believed. Burning women was seen as necessary and proper, and it was expected that government officials would engage in the task. It was all done according to rules and laws: there was no question of excited mobs of religious fanatics armed with pitchforks. Killing women was a task organized by the state with all the proper trappings.

Witch hunting also had a monetary side. In many cases, the property of the executed witches could be confiscated and the profits distributed among the people engaged in the task. It was an activity that was both profitable and seen as necessary, a little like, in our times, rat extermination. So, how did people stop engaging in it? There was no lack of witches available. Given a sufficiently intense torture, almost anyone would confess to having had sex with the devil.

Remarkably, witch hunting faded out by itself. There was no “Witch Burning Rebellion,” no “Witch Liberation Movement.” Even during the decline phase, there are no records of anybody explicitly condemning witch hunting. For nearly a century after executions stopped, condemning the madness remained outside the Overton Window of the time. The “Illuminists” of the 18th century spoke scathingly about all superstitions, but that was when the killings were already almost over, and they never singled out witch burning as an especially odious crime.

We have to wait for 1841 to find an explicit condemnation of witch hunting, with Charles MacKay in his "Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of the Crowds,” where we find this remarkable sentence:

“Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, and one by one.”

MacKay never heard the term “meme,” and he had no idea that viruses existed, but this sentence perfectly sums up how epidemics, virtual or biological, behave. A virus or a meme expands in herds, infecting people who come in contact with an already infected person. Conversely, people regain their sanity (mental or biological) one by one.

Even though healing occurs at the individual level, it has collective consequences when it generates “herd immunity.” It is a concept that was mistreated beyond imagination during the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is both logical and simple to understand. When a sufficient number of people resist infection, a sick person can’t infect as many people as is needed for the epidemic to continue. And this is the key to the whole story. You cannot heal a sick person by being sane yourself (mentally or physically), but you can stop the progress of the infection by being sane in such a way to create herd immunity.

If you want to free people from the evil memes that took possession of them, you cannot do it by reasoning or by your example. This is why so many actions by well-intentioned people turn out to be counterproductive. Think about the “Extinction Rebellion” movement. It was, and still is, so effective in generating a negative counter-reaction that you may legitimately suspect that it was paid for and organized by those whom it pretended to fight.

So, if you want to do something to stop he current wave of madness engulfing the world, first of all, you have to heal yourself. You need silence. You need a pause. Turn off the TV. Don’t engage in flames on the Web. Ignore the screaming of the trolls. Don’t respond to insults. Spend time with your children, your family, and your friends. There is a real world around you, and in the real world, you can recognize evil when you see it. You can do that. And when you have identified evil, you cannot be infected by it and you become a barrier against other people becoming infected.

Eventually, killing and burning innocent people by aerial bombing will be seen just as today we see burning innocent women at the stake: a moment in history when folly had overcome the collective human mind. It will take time, but we may still hope for a better future.

From time immemorial, authorities (rulers and clerics) have done everything to increase wealth to enjoy the power extracted from that. Summarized as a class of people not bothered by any form of conscience.

According to the saying "As people's wealth trickles up (to the authorities) while their (psycho/sociopathic) behavior trickles down", corruption becomes the uncrowned emperor.

This mechanism is in full swing today - think arms industry, medical racketeering (over half of Western population has at least one chronic disease) and the "designed to addict" junk food industry.

Hence religions became tools for enrichment as well, whether buying "forgiveness" via confession, next lives for a more meritorious life etc. and to the extent that for laymen the original intent of practices (wellbeing instead of (useless) wealth) became lost.

The originals had in common that "the world" of every organism is experienced in a subject-object relationship and is exclusive for that organism (because 2 organisms can't fill the same space). The discovery of ancient "accidental" yogis, mystics and equivalents was that the subject can exist without such a relationship IOW singular. Philosophically a can of worms, which was circumvented by sayings like "the Tao that can be discussed isn't the Tao".

The individual discovery that "subject" exists without subject-object relationship is accompanied by a sense of wellbeing that can't be attained in any other way so makes realizers far less vulnerable to authorities.

How many 20th centuries do we need to convince us that humanity has a death wish? Apparently more than one.

Freud's Civilization and Its Discontents gives us insight into how fascist dictatorship, once it starts, transforms into a death cult in a predictable sequence. The sociologist Ernest Becker adds a codicil in his posthumous meditation Escape from Evil, in which he notes that humans happily clutch at the lie that we can compel others to experience our deaths and our sufferings for us. That unconscious mechanism, Becker notes, gives rise to human evil in all its cruel and self-defeating manifestations.

Unless interrupted by conscious courage, humanity's unconscious periodically escapes the prison of normalcy. When it does, lots of us die, physically or otherwise.